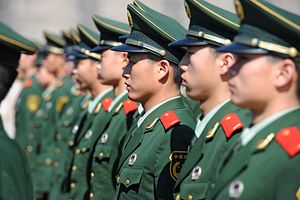

The National People’s Congress is wrapping up in Beijing this week, but the final meetings are still attracting widespread attention. On March 11, Chinese President (and Chairman of the Central Military Commission) Xi Jinping attended a meeting of NPC delegates from the People’s Liberation Army.

Interestingly, both Chinese and Western media focused on similar themes from Xi’s remarks. Xinhua’s English language article used the title “Xi vows no compromise on national interests” (the Chinese language article, while far more thorough in its coverage of Xi’s speech, used a similar title). The Wall Street Journal also focused on Xi’s comments regarding defending national interests. Both articles gave prominent position to one of Xi’s comments in particular: “We expect peace, but we shall never give up efforts to maintain our legitimate rights, nor shall we compromise our core interests, no matter when or in what circumstances.”

These sorts of comments should not surprise anyone. For one thing, we’ve heard them already, as recently as last week when China was defending a double-digit increase in its military budget. For another thing, militaries around the globe exist to do exactly what Xi tasked the PLA with doing: protecting national “rights” and “interests,” however the people in charge choose to define them. China’s military goals are complicated, of course, by the fact that in the South and East China Sea areas that China claims as its sovereign territory are disputed by other nations, making it tempting to read remarks like Xi’s as an implicit threat.

But interpreting Xi’s speech to the military through the narrow lens of what they might mean for the South China Sea disputes risks missing the broader implications. The main focus of Xi’s speech was not on the need to defend China’s national interests, but on how to best equip to PLA to do that—through reforms. Xi called on China’s armed forces to use a “spirit of reform and innovation to establish a new phase for national defense and the armed forces.”

Since coming to office, Xi has placed an emphasis on modernizing and strengthening China’s military. Much has been made of the technological aspects of this goal—I’ll leave such analysis to the more capable authors on our Flashpoints blog. But Xi also mentions repeatedly that achieving this goal is not a given. Steps to modernize and strengthen China’s army are dependent, in Xi’s mind, on successfully implementing a series of reforms. In other words, Xi wants to “modernize” not only China’s military technology, but the military structure as a whole.

This is no mean feat. Xi himself outlined the scope of the challenge in his speech on Tuesday: “We must solve the systemic barriers, structural contradictions, and policy issues that restrict the construction of national defense and the armed forces, and deeply push forward the modernization of the armed forces’ organization.” Xi is talking about reorganizing China’s military, which currently suffers from disconnects between local military regions and the different force branches. The announcement last year of China’s new National Security Commission, with Xi himself at the head, was an early step in restructuring the control of the military and security apparatus. The process continued with the announcement of a new joint operational command structure for the armed forces, but details on what exactly this means are still vague. As with any reform, it will be an uphill battle to get vested interests (in this case, military officials) to agree to constrict or even give up power.

Given the challenges, it’s remarkable that Xi has moved to restructure China’s military so quickly. Hu Jintao, Xi’s predecessor, had to wait two years after assuming Chairmanship of the Communist Party of China before he took over the position of Chairman of the Central Military Commission. In fact, according to many observers (including former U.S. Defense Secretary Robert Gates), Hu never had full control of China’s military. By contrast, Xi assumed control of the military immediately and took less than a year to begin rolling out his vision for reorganizing and modernizing the armed forces.

Xi has also made the military a target of his wider anti-corruption efforts, cracking down on the illicit use of government funds for lavish banquets, luxury cars, and extravagant buildings. However, punishments (at least publicly announced ones) for corrupt guilty military officials have lagged far behind those dealt out to their civilian counterparts. One of the few exceptions was Lt. Gen. Gu Junshan, who reportedly had a solid gold statue of Mao Zedong among other luxury goods at his home.

Effort to modernize the PLA’s organization structure, including the fight against corruption, will be more difficult than the modernization of China’s technology. How Xi reorganizes the military (if he is able to do so) will have lasting consequences for how military decisions are made and the speed at which orders are carried out. The modernization of China’s military technology is important, no doubt. But the reforms to the military’s very structure, from increasing coordination between the army, navy, and air force to consolidating control of China’s military regions, could have an even bigger impact on the security situation in the Asia-Pacific.