While still struggling to overcome domestic challenges to her administration, President Park Geun-hye faces daunting foreign policy issues ranging from North Korea’s missile provocations to endangered South Korean business interests in Iraq. To make matters worse, the Shinzo Abe government’s reinterpretation of Article 9 of the Japanese constitution, allowing Tokyo to deploy its self-defense forces abroad, has further complicated Seoul’s relationship with its neighbor.

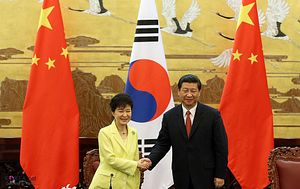

Amidst these difficult times, President Xi Jinping’s upcoming official state visit to South Korea bolsters President Park’s foreign policy position by providing her with much needed diplomatic capital.

Much of the media attention is currently focused on the fact that President Xi is making the visit to Seoul without plans for a similar overture to Pyongyang, perhaps indicating Beijing’s frustration with Kim Jong-un. Given these signs, there are hopes that China will use the upcoming visit to establish a closer working relationship with South Korea on pressuring North Korea. Nonetheless, the Sino-South Korean relationship in recent years has evolved beyond their shared concern for Pyongyang’s nuclear ambitions and frequent provocations.

One such area is the two governments’ joint efforts in criticizing the Abe administration’s foreign policy posture. China’s close collaboration with South Korea in erecting memorials to the Korean people’s struggle for independence at symbolic locations across Manchuria and its own efforts to highlight Japanese atrocities in China during the Second Sino-Japanese War have acted as signals to Tokyo, emphasizing how unresolved historical issues such as compensation for “comfort women” obstruct closer ties between the three countries. More pertinent to present foreign policy issues, condemnation of Japan’s past militarism double as expressions of displeasure towards Tokyo’s present intention to exercise its military in a broader capacity.

From President Park’s perspective, closer cooperation with President Xi in this area also sends a message to the United States, which has welcomed the Abe government’s reinterpretation of the Japanese constitution. Seoul has correctly recognized that Washington’s foreign policy outlook in the region focuses on East Asian nations taking on a larger share of the defense burden in the West Pacific. In this context, Blue House frequently underscores its intentions to step up South Korea’s military presence in the region through closer cooperation with Japan. However, by drawing close to Beijing on issues which already have substantial backing in Washington, Seoul can emphasize to the White House how Japan’s current posture hurts both South Korea and Japan’s ability to effectively take on bigger security roles in the region.

However, there are limits on how much President Park can utilize the close relationship between Seoul and Beijing to influence the evolution of the strategic relationship between U.S., South Korea, and Japan. These limitations are in part a reflection of the fact that Seoul is in no position to draw the figurative “red line” when it comes to the relationship with Tokyo. Economically and diplomatically, Japan remains undoubtedly a crucial partner in the region. And while South Korea’s relationship with China has warmed significantly over the past twenty years, at the end of the day, Seoul shares fewer foreign policy positions and concerns with Beijing than Tokyo.

A large part of the problem is that the South Korean government does not have the domestic support to pursue closer ties with Japan under present circumstances. Clearly, the task ahead for policymakers in Seoul and Tokyo is to figure out a way to sell to the South Korean people a foreign policy that stresses more intimate bilateral relations between the two countries.