NATUNA ISLAND – What might be called “homeland security” is tight at Natuna Island, and it should be – this may be the next bite China takes out of the South China Sea.

Upon landing at Natuna (also called Natuna Besar), Indonesia’s largest island within the hotly contested South China Sea, foreigners must register and provide copies of their passports, even though all arriving flights are domestic. No photos are allowed until well outside the airfield because it doubles as an Indonesian Air Force base. When departing the island, all foreigners must “check out” with security personnel, who quiz visitors on where they have been during their stay, and their routing into and out of the area. Even a casually met off-duty naval officer will make pointed inquiries about a visitor’s activities on the island.

Given that Beijing has recently promulgated a map with boundaries that claim a swath of sea that may include the Natuna Islands as part of its territory, the increased security is understandable, but the paucity of military clout on this significant Indonesian border outpost is a stark reminder that Beijing faces little hard resistance to its ongoing annexation of the South China Sea. Over the past two years, China has reinforced its territorial quest through intimidation, naval patrols, localized blockades, oil rig placements, ramming of fishing vessels, and construction of facilities on numerous small islands and sub-surface shoals.

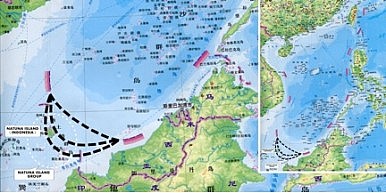

How to connect Beijing’s speculative dashes? The 2013 map is by SinoMaps Press, an arm of the Chinese government (with thanks to Euan Graham for a digital image). Dashes in pink denote Beijing’s claimed “nine-dashed line” (now comprising ten dashes). Superimposed black dashed lines, by the author, show hypothetical ways of connecting the two southernmost dashes in Beijing’s self-proclaimed southern boundary. All three hypotheticals would overlap with Indonesia’s claimed territory around the Natuna Islands, including major natural gas fields.

Until recently Indonesia seemed immune to these hostilities, and its government offered itself as an honest broker among the disputing neighboring states – China, Vietnam, the Philippines, Malaysia, Brunei, Taiwan – but with Beijing’s recent inclusion of the area around Natuna in its newly sanctioned maps (and on Chinese passports), Indonesia’s incoming President Joko Widodo may find China’s aggression to be one of the first items in his inbox when he assumes office in October.

Two of three air force hangars at Natuna airfield. Photo by Victor Robert Lee.

He will also find that the air force base at Natuna as well as the “naval base” there are unlikely to provide much front-line defense. The air force base has an abundance of housing quarters – more than thirty small buildings – but only three modest aircraft hangars. The fact that there are no military aircraft visible at the base may demonstrate stealth, or perhaps the absence of aircraft.

On the lawn of an adjacent navy compound, two dozen personnel including several women were admirably practicing martial arts, but the only navy vessels on the island are two small and lightly armed patrol boats and a rigid inflatable boat (RIB), all tied to a deteriorating pier. Even granting that some naval assets may have been transferred recently to a base in the Anambas Islands, 210 miles to the southwest of Natuna, the strict no-photo regulation may be driven by a wish to hide weaknesses rather than to keep military secrets.

In March of this year, Indonesia’s government for the first time acknowledged that China’s unilateral claims on most of the South China Sea include parts of Indonesia’s Riau province, to which Natuna and other islands belong. Indonesia, a nation of 250 million people, may, despite its government’s polite attempts to carve itself out of the South China Sea conflicts, find itself the latest victim of Beijing’s acquisition campaign.

The Natuna archipelago has been the subject of an Indonesia-China tug-of-war before. Until the 1970s the majority of Natuna residents were ethnic Chinese. Deadly anti-Chinese riots plagued Indonesia in the 1960s, early 1980s, and again in 1998, leading to a decline of the ethnic Chinese population on Natuna from an estimated 5,000-6,000 to somewhere over 1,000 currently. Many ethnic Chinese in the broader region believe to this day that a secret meeting (never publicly confirmed) was held between Deng Xiaoping (China’s premier from 1978 to 1992) and Natuna islanders of Chinese origin, who asked that Deng either back their bid for independence from Indonesia, or bring their island under Chinese suzerainty.

Neither happened, and as part of a nationwide transmigration initiative, the Indonesian government in the 1980s started to relocate ethnically Malay Indonesians to Natuna, for the stated reasons of importing skills and relieving population pressures on the overcrowded main island of Java, and, as perceived by local Chinese Indonesians, for the unstated reason of swamping the ethnic Chinese population with “real Indonesians”; that is, people of Malay ethnicity, who now number approximately 80,000 in the Natuna Islands group.

In 1996, Indonesia, perceiving that China had signaled territorial claims on the seas near Natuna, carried out its largest-ever naval exercise, sending almost 20,000 personnel to the Natuna Sea. Jakarta wanted to demonstrate its resistance to any Chinese attempt to control the blocks of sea being developed for natural gas production in partnership with American oil companies. The actions by the Indonesian Navy and Air Force at the time appeared to deter China’s ambitions, but now, after eighteen years of a vastly greater rate of military expansion by China, it is unlikely that Indonesia’s gumption in similar circumstances would be as credible.

Deng Xiaoping’s wait-it-out mantra regarding the East and South China Sea disputes was: “This generation is not wise enough to settle such a difficult issue. It would be an idea to count on the wisdom of following generations to settle it.” But Deng’s sentiment has been superseded. China’s new president, Xi Jinping, who has effectively taken over most of the South China Sea by force of his navy, appears to be abiding by the dictum of Communist China’s first leader, Mao Zedong, who said, “Political power grows out of the barrel of a gun.”

At the time of the 1996 Indonesian military exercises to defend the Natuna area, a prescient regional specialist at the Indonesian Institute of Sciences, Dewi Fortuna Anwar, was quoted as saying, “China respects strength. If they see you as being weak, they’ll eat you alive.” Dr. Anwar went on to become an internationally recognized scholar and is now an advisor to Indonesia’s vice-president; her words ring true today in the South China Sea.

Victor Robert Lee reports on the Asia-Pacific region and is the author of the literary espionage novel Performance Anomalies.