Last week, in the official preview of the APEC summit given by China’s foreign minister, Wang Yi noted that China wants forward progress on the Asia-Pacific Free Trade Area (FTAAP). However, a recent report from the Wall Street Journal indicates that the U.S. is trying to shut down those discussions.

As the WSJ notes, the idea of FTAAP has been around for years. The U.S. initially supported the idea, but recently the Obama administration has shifted its focus to the Trans-Pacific Partnership (TPP), a “high standard” trade agreement that would include 12 countries on both sides of the Pacific – Australia, Brunei, Canada, Chile, Japan, Malaysia, Mexico, New Zealand, Peru, Singapore, the U.S., and Vietnam – while excluding China. The Obama administration places a heavy emphasis on the TPP as the economic pillar of its “rebalance to Asia,” and apparently is not keen to see momentum diluted by the introduction of a new trade arrangement.

The Wall Street Journal reports that the U.S. pressured Beijing to drop two provisions dealing with FTAAP from the draft APEC communique. One provision called for APEC to begin a feasibility study for FTAAP, which would be the first formal step in negotiating the new FTA. The other provision set a target date of 2025 to close the deal. According to the Wall Street Journal, both provisions were removed from the draft after the U.S. protested.

According to estimates from the Peterson Institute of International Economics cited by the WSJ, FTAAP would represent a “win-win” for the U.S. and China – although China would “win” far more. PIIE estimates that, by 2025, the FTAAP would help the U.S. gain about $626 billion in exports, while China would gain a whopping $1.6 trillion. Under the TPP arrangement, the U.S. would gain far less in exports (about $191 billion) but China would actually stand to lose roughly $100 billion in exports as the TPP nations would shift their trade focus to other TPP member economies.

From a Chinese perspective, then, the U.S. move to block FTAAP smacks of containment. When Chinese analysts complain of a “Cold War” or “zero sum” mentality, this is exactly the sort of political calculation there are talking about: Washington would rather minimize its own gains to ensure maximum Chinese losses. Plus, U.S. pressure to kill FTAAP mirrors a similar attempt by Washington to persuade its allies and partners not to sign on to China’s Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank. To Beijing, it certainly looks like Washington is out to block any regional economic initiatives that stem from China.

From a U.S. perspective, though, this decision is simply pragmatic. The TPP negotiations are close to being finalized, but recent deadlocks have stalled progress. Under these circumstances, the Obama administration likely feels that introducing a new, even larger trade proposal would sap what little momentum remains for the TPP. FTAAP negotiations would be a long, messy process (as seen by China’s original target date of finalizing negotiations by 2025) and may ultimately end in failure given the number of countries and divergent interests involved.

Plus, the Obama administration wants to use TPP to ensure that other countries meet the United States’ “high standards” in defining free markets and ensuring intellectual property rights. A parallel agreement that is both more inclusive and less stringent in its requirements would kill any impetus for regional governments to strive to meet those standards.

When it comes to regional trade arrangements, the U.S. and China are simply not on the same page. If the U.S. takes FTAAP off the table, China may simply return to emphasizing the Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership (RCEP), a proposed free trade bloc that would include the ASEAN member states plus Australia, China, India, Japan, South Korea, and New Zealand (with the U.S. on the outside looking in).

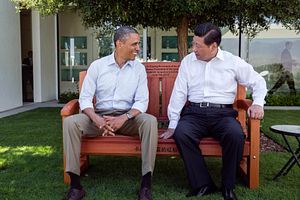

There is a glimmer of hope for economic cooperation on the bilateral level, however. As Elizabeth Economy noted in her APEC preview, in a best case scenario the U.S. and China can begin to make some real progress on a bilateral investment treaty during Obama and Xi’s bilateral meetings.