Two weeks ago, ISIS destroyed the remains of the ancient Iraqi city of Hatra, a UNESCO World Heritage Site.

Hatra is a testament to the region’s resilience, having withstood repeated foreign attacks throughout its 2,000 year history. Once a major trading center, it now rests as a symbol of what was a cosmopolitan hub populated by a mixture of peoples. Its blend of Roman and Hellenistic architecture with Arab features is a vivid reminder of the region’s rich cultural history and a flicker of hope of what it could have become.

UNESCO, the UN’s cultural agency, and IESEC, its Islamic counterpart, denounced the city’s destruction as a “war crime” and a “turning point in the cultural cleansing” of Iraq. Others around the world, such as the Arab League, have condemned the attacks.

But ISIS’s iconoclastic crusade is nothing new.

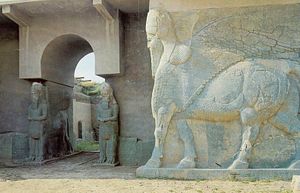

Last July, ISIS demolished shrines cherished by Jews, Christians, and Muslims alike, such as the tomb of the Prophet Jonah in Mosul and the shrine of Prophet Seth, considered to be Adam and Eve’s third son. A couple of weeks ago, the deplorable scenes of ISIS militants toppling and smashing statues and carvings in Mosul’s museum sent shock waves throughout the international community, providing insightful evidence of ISIS’s complete disregard for cultural property. A few days later, ISIS fighters bulldozed an archaeological site dating back to 900 B.C. at the city of Nimrud, an ancient capital of the Assyrian Empire.

These are not sporadic attacks; they are part of a systematic campaign to wipe out humanity’s cultural legacy.

How can the international community prevent these egregious acts of cultural violence? Despite public denouncements, no concrete action has so far been taken by any government or intergovernmental organization.

Poor security in the region has enabled ISIS to seize control of vast territories in Iraq and Syria, allowing it to enforce its puritanical interpretation of Islam unabated.

Earlier last week, the Iraqi Ministry of Tourism and Antiquities asked the international community to intervene to help it protect its cultural heritage. Last Monday, the U.S. issued a statement ruling out airstrikes to protect Iraqi antiquities for lack of sufficient partners “on the ground.” This is not the first time Western powers have declined to intervene to protect Iraqi cultural property. During the Gulf War, the U.S. and British governments promised to protect the Iraq Museum in Baghdad, but failed to translate their resolve into practice. The result was major looting of thousands of antiquities in the museum.

In a climate of despair, it is difficult to contemplate solutions. But there are a number of ways that both states and other actors around the world may help prevent, protect, and prosecute these barbarities.

First, efforts must be taken to digitally preserve what may be too late to protect in real life. Technology companies could act as key players by providing the technical infrastructure to document and record cultural property in at-risk regions. Google’s Cultural Institute is a good example of how this could work, having partnered with hundreds of museums “to host the world’s cultural treasures online.” Street view and virtual reality technology could also be harnessed to digitally capture landscapes and sites.

Second, international instruments should be used to promote best practices and prosecute transgressors. The protection of Iraqi cultural heritage like the city of Hatra is the collective responsibility of all 191 states that are parties to UNESCO’s 1972 World Heritage Convention, including the United States, China, and Russia, as well most African and Latin American countries. Although Iraq signed the Convention, it never ratified it, which means that it never took affirmative steps to internalize international norms relating to the protection of cultural property. It also never ratified the 1970 Convention on the Means of Prohibiting and Preventing the Illicit Import, Export and Transfer of Ownership of Cultural Property. ISIS has been reported to resell cultural artifacts to fund its operations. The ratification of these Conventions would be a firm step to help Iraq align its institutions and laws with international norms.

Iraq is also not a party to the Rome Statute, which means that it cannot refer the matter to the International Criminal Court. Under the Rome Statute, the intentional and discriminatory destruction of “buildings dedicated to religion” and historic monuments qualifies as a war crime. This interpretation has been upheld by international courts, including the International Criminal Tribunal for the former Yugoslavia. In the meantime, other states should step in to prosecute these crimes under the principle of universal jurisdiction, which enables any country to prosecute such crimes.

Third, States and other actors should also focus on practical solutions to rescue cultural property in cities at risk of ISIS pillaging. Much like refugees persecuted for their beliefs, cultural property is targeted because of the cultural and religious values it represents. Museums in the region and around the world should offer to host at-risk cultural property until security in the region is re-established. The repatriation of these objects could prove problematic, and uncertainty about who pays for shipping and maintenance in the interim may discourage benefactors. But these material costs must be weighed against what is at stake: thousands of years of humanity’s art, history, and culture.

Finally, the issue of reselling stolen artifacts must also be addressed. An international task force, comprised of both public and private sector players, should be formed to help Iraqi agencies survey at-risk sites and itemize its cultural property. This will assist law enforcement agencies around the world to better trace looted property as they make their way into the black market and auction houses.

Though these strategies all pose their own challenges, the world cannot simply sit and watch as the cultural footprints of civilization are forever erased.

Thiago Velozo is the founder of Curiously Labs. Lucas Bento is an international lawyer in New York.