To endeavor to seize the strategic initiative in military struggle, proactively plan for military struggle in all directions and domains, and grasp the opportunities to accelerate military building, reform and development.

– Chinese Military Strategy, Chinese Ministry of National Defense, May 26, 2015.

On May 26, the State Council Information Office released an English-language version of the Chinese Military Strategy. Short, sweet, and immensely more readable than its American counterpart, the PRC’s military strategy is notable for its transition to an overt, “active defense” posture for Chinese military forces. Among the many salient points is the emphasis on gaining the strategic initiative, which is one of eight specified strategic tasks for the Chinese military.

This is not a new development, but recent activities in the South China Sea (SCS) illustrate the reality that China has already seized the strategic initiative in those waters. Force dispositions in the SCS make it clear that the PRC has no intention of surrendering the initiative. A passive U.S. response will only continue to demonstrate to China the usefulness of its approach, while traditional flexible deterrent options are both unnecessarily provocative and likely to be ineffective. A comprehensive, long-term engagement and modernization strategy focused on Partner Nation (PN) and U.S. airpower may provide an opportunity for the U.S. to reverse PRC gains in the SCS and prevent further gains.

Airpower, particularly airpower employed by partner nations, is the necessary backbone of a strategy to effectively neutralize the political effectiveness of the PRC’s island forts in the South China Sea. A robust engagement strategy, combined with a modernized American bomber force, will allow the United States to credibly project power or assist local defense efforts, even in cases where local basing for U.S. forces is unavailable. This proposed U.S. strategy has three elements; new defense relationships, a revised toolkit for building up partner nation air and seapower capabilities, and a modernized long-range bomber force.

Geography

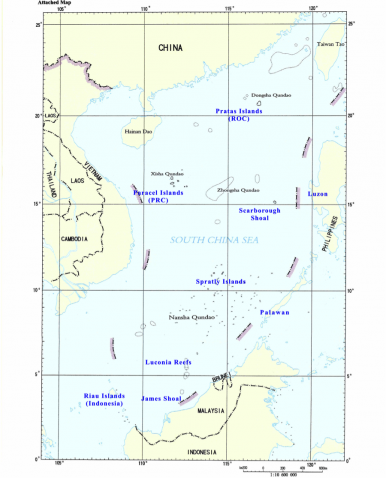

Any discussion of the South China Sea has to start with the geography. China’s claims essentially encompass the entire sea, based on the remnants of the 11-dash line inherited from the Republic of China in 1947. Now referred to as the “nine-dash line” (two were deleted by Zhou Enlai), the line encompasses territory that has historically been claimed or occupied by other nations, including marginal reefs, shoals, and sandbars. Some of those marginal points have been occupied by China and other nations with claims, and a number have been expanded into artificial islands complete with military facilities, including airfields.

While much has been said in the press about China’s militarized artificial islands, fortified islands have all of the disadvantages of an aircraft carrier, without the mobility that makes the carrier worthwhile. As the Japanese discovered in WWII, fortified islands are locations where forces are dangerously concentrated into tight spaces with limited materiel, fuel and munitions. Militarily, small island bases are easy to isolate, hard to defend, and they concentrate forces in the most unfavorable manner – when they are most vulnerable to attack. They can easily be turned into a liability. In peacetime, by contrast, the bases are effective at expanding the ability of the PRC to observe, act and intimidate neighbors. The challenge, then, is how to neutralize their effect in peacetime.

Figure 1: PRC Map of the SCS showing the 9-dash line, submitted to the UN in 2009 (English labels added)

The South China Sea is commanded by the landmasses around it. No collection of small, static island bases will provide command of it. Vietnam, Borneo, Luzon and Palawan dominate the geography. South of the Paracels, Vietnam and the Philippines have a positional advantage over the SCS compared to mainland China or Hainan Island. Countries with substantial nearby territory, notably Indonesia, Malaysia, Vietnam, the Philippines and Brunei, have the potential to offset some of China’s military advantages – but only if they can hold Chinese military elements at risk.

A New Defense Architecture

If we are to successfully contain the PRC’s ambitions in the SCS, we will have to change the defense architecture in the region. Only four countries hold a commanding position over the SCS: China, Vietnam, Malaysia and the Philippines. Arguably, the PRC pairs the largest military with the poorest geographical position. A U.S. containment policy can be immeasurably improved with the addition of the active participation of one or more of these critical neighboring nations. Even without U.S. permanent basing, established defense relationships and an improved PN military posture can provide a bulwark against PRC aggression.

Vietnam, which has a thousand years of Chinese occupation in its history, is also the most recent victim of full-scale Chinese military aggression, having suffered an invasion by the PRC in 1979. Vietnam has also suffered more casualties in the South China Sea in direct conflict with China than any other nation. With a commanding position over the SCS, claims to the Paracel Islands and a robust basing structure, Vietnam is logically the highest-payoff country in the region with which to improve a defense relationship, with or without forward basing accessible to the U.S. The future of military cooperation is currently somewhat limited because Title 22 CFR 126.1 prohibits lethal military aid to Vietnam; waiving this prohibition with respect to maritime weapons systems has already allowed an expanded, if limited, defense relationship with Vietnam. The waiver could be expanded to encompass aviation capabilities, and Senator John McCain has announced a plan to introduce legislation that would remove CFR 126.1 restrictions on Vietnam.

Malaysia, which already has an existing security cooperation relationship with the U.S., commands the south approaches to the SCS via the island of Borneo. It maintains claims to some of the Spratly Islands, and exerts control over a number of reefs, shoals, and the airfield on Swallow Reef. There are seven militarily significant Malaysian airfields on Borneo, making it substantially more robust than any PRC landfill basing structure. The Royal Malayan Air Force operates a mix of modern U.S., Russian and European aircraft covering a wide range of roles. From an aviation standpoint, Malaysia has a small but capable Air Force, and a defense doctrine that has focused heavily on self-reliance.

The Philippines is the only one of the three partners bordering the SCS that has a mutual defense treaty with the United States, dating from 1961. Unfortunately, the Philippine Air Force is a shadow of the organization that the U.S. helped build up after Vietnam. Despite a 20-year old modernization plan, the Philippine Air Force lost its ability to operate jet fighters ten years ago and suffers from aging equipment, poor infrastructure, an ad hoc military procurement system and poor morale. In effect, the PAF is an internal security force and the Philippines is entirely dependent on the U.S. for external defense.

The Wolverine Strategy

The process of strengthening local partners to compete with a regional hegemon is often referred to as the “hedgehog” strategy. A hedgehog is a difficult challenge for a predator intent on a quick meal. A hedgehog doesn’t have to be impossible to eat, it just has to be more difficult and less worthwhile than the other meal options. A wolverine, on the other hand, is a nasty, aggressive predator that is not only difficult to eat, but dangerous to be around and worth avoiding. A “wolverine” strategy, intended to improve the offensive counterair and countermaritime capabilities of partner nations, would hold part of the key to neutralizing China’s initiative.

The PRC’s claims in the SCS have no standing in international law, and only very tenuous historical backing. Many of the islands have been only occasionally inhabited for centuries, some remain claimed by the Republic of China, and some have been seized by force by the PRC. In 1974, the PRC seized the Crescent Group of the Paracels from the Republic of Vietnam. In 1994, Mischief Reef was occupied during a lull in Philippine Navy patrols and in 2012 the PRC abrogated a U.S.-brokered agreement which would have pulled back PLAN and Philippine Navy vessels. A three-year blockade of the Philippine Marine detachment on Second Thomas Shoal is ongoing. The PRC has been aggressive in pursuing SCS claims, not only within the 200-nm Exclusive Economic Zone (EEZ) of other nations, but also within the territorial 12-mile limit of the Philippines, Brunei and Malaysia.

China is a signatory of the U.N. Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS), but believes that it does not apply in the SCS. To date, none of the adjacent countries has resisted PRC encroachment militarily, with the notable exception of Vietnam. This can only change if those countries become strong enough to make PRC advances costly or easily reversed. For local defense within a country’s EEZ, land-based airpower is the decisive force because Vietnam, the Philippines and Malaysia could all potentially maintain air superiority within 200nm of their shores, while China would be challenged to operate at a much longer distance. If the countries surrounding the SCS had robust, offensive air and sea capabilities, not only would they be better prepared to resist PRC aggression, they would also be able to reverse temporary gains and raise the costs of Chinese intervention.

U.S. participation in developing offensive air and sea capabilities is critical, but at this juncture not particularly feasible. The U.S. has no lethal, affordable and transferable air or naval systems that our regional partners can afford to purchase, operate and maintain in sufficient numbers. In the 1970s, the U.S. Air Force provided a large number of air forces worldwide with Vietnam-surplus aircraft to provide an effective bulwark against a common Communist-inspired threat. A-37s, F-5s, A-7s, C-7s, C-119s, C-123s, O-1s, O-2s and OV-10s were provided to a number of air forces. Those aircraft are now only marginally operational, if at all. The U.S. now have few alternatives to offer while, at the same time, demand for U.S. assistance with air forces is only growing. If a PN cannot afford an F-16 with a midlife upgrade, we cannot supply them with combat aircraft. Similarly, we do not build naval vessels that can be used effectively by less-capable partners – our best options are retired FFG-7 frigates and the occasional long-endurance cutter. Littoral combat ships are too expensive by an order of magnitude, and we do not build a surface combatant like the Pegasus-class hydrofoil, Skjold-class corvette, or Type 022 fast missile boat. If we were to attempt to execute a Wolverine Strategy, we are short the necessary tools – the U.S. will have difficulty providing common hardware, effective training, and the most important aspect of all – a long-term relationship that helps shape partner militaries to be a key ally for a global effort with values common to both.

Figure 2: PRC Claims in the SCS overlaid on 200 nm EEZ lines (Goran tek-en)[i]

This is an acute problem in Southeast Asia, as U.S.-built combat aircraft have reached the end of their service lives. The last U.S. export fighter, the F-5E Tiger II, has so far been replaced by non-U.S. fighters, forfeiting a major security cooperation opportunity. The last remaining F-5s in Southeast Asia will retire in the next five years with no American replacement options except the much more expensive F-16, F-18 and F-15E.

| Country | Replacement | Status |

| Philippines | T-50 Golden Eagle | On order, none delivered |

| Thailand | JA.39 Gripen (12) | F-5 to be retired by 2020; additional JA.39 cancelled |

| Vietnam | Su-27 FLANKER | Subsequently replaced by Su-30Mk2 FLANKER G |

| Singapore | F-15SG (12) | F-5 to be retired by 2020, replacement undetermined |

| Taiwan | TBD | F-5 to be retired in 2019, replacement undetermined |

| Indonesia | Likely Su-35 | Competition in progress, upgraded F-5 still flying |

| Malaysia | MRCA (unfunded) | F-5 retired in 2015; no funding for replacement |

If we are to successfully execute a Wolverine Strategy, we will have to do something about both our air advisory capability and our stable of available aircraft. Combat variants of the T-X trainer (AT-X and FT-X) might well serve as a mid-term, exportable fighter in the mid 2020s. Similarly, ACC’s OA-X (AT-6B or A-29B) could help rebuild the essential skills needed by the Philippines to allow an effective transition to a multirole force – and those aircraft are ready today. If the U.S. were also to design and build small missile combatants akin to the PLAN’s Type 022 Houbei-class, partner nations could add small, lethal combatants to the list of capabilities used to offset the PRC’s current maritime superiority over other regional navies. Most importantly, we must accompany any advisory effort with a long-term commitment akin to Plan Colombia, which took a decade, but resulted in a well-equipped, thoroughly professional Fuerza Aérea Colombiana.

The Bombers

The final ingredient is a modernized long-range bomber force, consisting of LRS-B, B-2, and upgraded B-52J. (The B-1B is simply too fuel inefficient, and has such low availability ratings, to be cost-effective to keep in the inventory. The loss of B-1s will be offset by new LRS-B and by moving additional B-52 from storage into operational units.) The long distances typical of combat in the Pacific, and the increasing range of the PRC’s missile threat, may necessitate operating from well outside the region. Bombers may operate from foreign locations such as RAAF Tindall or Diego Garcia, but a re-engined B-52J could also operate unrefueled into the SCS from distant bases like RAAF Amberly or U.S. territory such as Wake, Guam, or even Hawaii. With modernized sensor systems including inverse synthetic aperture (for ship identification) and pulse-Doppler (for air to air situational awareness) modes, the bombers will be able to support countermaritime operations in and around the South China Sea.

Against the Soviet Navy, a three-ship flight of Harpoon-armed B-52Gs was a formidable force, and might well have proven a dominant force in the North Atlantic. Armed with modern antiship weapons such as the Naval Strike Missile or improved Harpoon, a loaded flight of B-52s has the salvo size to overwhelm naval air defenses from standoff range. In addition to antisurface warfare, the large capacity of the bombers could allow effective isolation of PRC military island installations by direct attack from standoff, or employment of precision standoff aerial mining capabilities exemplified by Quickstrike-ER and Quickstrike-P. Isolating island bases by preventing their resupply could effectively neutralize them – airbases require a lot of fuel to be effective, and air defenses require power generation, which is also fuel-intensive. Island bases isolated by standoff mining of the nearby waters may not be able to redeploy their heavy military equipment, which can then be attacked at leisure.

The small, congested conditions on fortified islands limit the effectiveness of active defenses, which cannot rely on a mobility doctrine due to the small area and cannot rely on tight emissions control due to the lack of supporting, land-based infrastructure. Moreover, bases built on landfill cannot be effectively hardened with underground facilities – a condition that also bedevils U.S. island bases in the region. Any hit by a weapon on an artificial island base is likely to have an outsized effect due to the congestion of assets.

Conclusion

The steady advance of the PRC’s territorial claims in the South China Sea has put the U.S. and partner nations at a disadvantage. China’s incremental approach relies more on the advantages of position and the threat of military force, which is often threatened but rarely used. China is able to get away with this kind of behavior because the competing nations do not have a regional defense arrangement and because the imbalance in force size and capabilities is substantial. However, Vietnam, Malaysia and the Philippines do have substantial geographical advantages over China in that each of them, alone, has a commanding position over parts of the South China Sea. The three of them together, properly equipped and supported by the U.S., could provide a robust counter to any isolated military presence that the PLA might establish outside the Chinese EEZ.

A combination of improved defense relationships and U.S.-built air and sea capabilities backed by a modernized long-range strike capability from USAF bombers would require a substantial investment in time and resources, but does not place the burden for offsetting China’s advances solely upon the United States. Given the rebalance to the Pacific, a robust engagement strategy is a necessary component of any U.S. effort to contain the PRC and assure Asian partners and allies that the rebalance is more than empty words. Airpower is a key component of this strategy and well-suited to the maritime challenges posed in the South China Sea.

Col. Mike “Starbaby” Pietrucha was an instructor electronic warfare officer in the F-4G Wild Weasel and the F-15E, Strike Eagle, amassing 156 combat missions and taking part in 2.5 SAM kills over 10 combat deployments. As an irregular warfare operations officer, Colonel Pietrucha has two additional combat deployments in the company of U.S. Army infantry, combat engineer, and military police units in Iraq and Afghanistan. The views expressed are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the official policy or position of the Department of the Air Force or the U.S. Government.