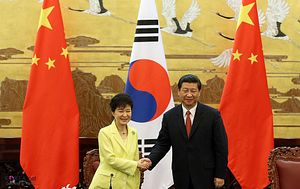

The question of whether South Korean President Park Geun-hye should attend the military parade in Beijing on September 3 to commemorate the 70th anniversary of victory in World War II has become the subject of (over)speculation in the media and among opinion leaders across the region.

As an example, Japan’s Kyodo News Agency reported that Washington delivered a message to Seoul, saying that the United States does not want Park to attend the coming parade in Beijing out of concern that her attendance could damage to the U.S.-ROK alliance and U.S.-Japan-ROK trilateral cooperation. But according to China News Service, a South Korean official denied that report in a telephone interview.

On the other hand, Shi Yinhong, Director of the Center on American Studies at Renmin University in Beijing, told Global Times that Washington’s real intention could be to “isolate” Russian President Vladimir Putin, not China. Shi pointed out that “after the Ukraine crisis, the United States does not want its allies to appear at any international venue where Putin also appears.” Putin has already confirmed his attendance at the parade.

Meanwhile, although most EU leaders apparently will not attend the coming military parade and other events in Beijing, Czech President Milos Zeman has decided to accept Beijing’s invitation, according to Chinese media. Zeman’s press secretary said that the decision was made by the Czech Republic as a “sovereign state.”

For South Korea, the problem of “to go or not to go” seems to have evolved into a different choice: to stay firm in the U.S.-ROK alliance or to slip into China’s embrace. At least, that’s the way the issue is being portrayed. This diplomatic issue thus helps demonstrates the enduring paradox of South Korea’s “middle power” strategy.

According to Kim Sung-han, the South Korean vice minister of foreign affairs and trade in former President Lee Myung-bak’s administration, “Middle powers are medium-size states with the capability and willingness to employ proactive diplomacy with global visions [emphasis added].” To go further, having truly “global visions” should put South Korea’s diplomacy in a larger arena, one that extends beyond bilateral ties with the United States and U.S.-Japan-ROK trilateral cooperation, however important they are to South Korea’s security from a traditional viewpoint. Currently, Seoul’s diplomacy toward Beijing can be seen a type of reagent or even catalyst to its “global visions” and its “middle power” strategy.

To take the issue of the coming military parade in Beijing in September, for example, whether Park should attend or not can be discussed in the context of South Korea’s possible “visions” of Beijing’s military parade. South Korea may choose to view this event as part of the world’s celebration of the Allied victory in World War II, which it obviously is. Alternatively, Seoul may choose to view the parade as an ambitious and nationalistic demonstration of China’s growing military strength and national pride, which may make some states uncomfortable.

If Park decides to attend, it will demonstrate a more confident and self-dependent diplomacy on South Korea’s part, although it may bring the potential for “disharmony” (not necessarily damage) in its traditional ties with the United States and Japan. If Park declines China’s invitation, it may symbolically keep the alliance relationship, especially U.S.-Japan-ROK trilateral ties, stable, but will likely not significantly improve those relationships (given the lingering tensions between Japan and South Korea). However, that choice will surely send a clear and not-so-friendly message to China, which is also quite understandable from a traditional viewpoint. The question is, does South Korea want to send this message, and does it want to send it in this way?