China’s military shipbuilders – now the world’s most prolific builders of large surface combatants and submarines – are leading a push to access local and global capital markets that other Chinese defense enterprises will likely emulate.

Between January 2004 and January 2015, the publicly listed arm of China Shipbuilding Industry Corporation, CSIC Limited and that of China State Shipbuilding Corporation, CSSC Holdings, raised a combined total of $22.26 billion from selling stock and bonds. This is approximately 20 percent more than the combined total that Huntington Ingalls, General Dynamics, and Lockheed Martin – three of the world’s largest and most sophisticated defense contractors – raised from the capital markets during that same timeframe.

Every dollar or RMB raised on the market and ploughed into upgraded yard infrastructure, staff, and warship equipment frees up military budget funds for other uses. Consider that each Type 054A frigate delivered to the PLAN likely costs approximately $360-375 million. Each billion dollars raised on the market thus can effectively fund naval hardware activity equivalent to the delivered cost of nearly three Type 054As—a substantial impact by any measure.

Quantifying the Activity

This analysis features the highlights of a paper my co-author Eric Anderson and I presented at the “China’s Naval Shipbuilding: Progress and Challenges,” conference held by the China Maritime Studies Institute at the U.S. Naval War College on 19-20 May 2015.

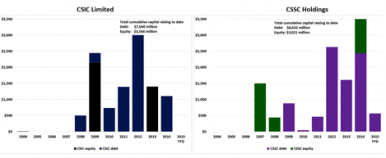

We created a unique proprietary dataset showing the number, type, and volume of capital markets transactions CSSC and CSIC executed between January 2004 and January 2015. These include both debt sales and equity issuances, and typically involved the companies’ respective listed arms: CSSC Holdings, Ltd. (SHA:600150) and CSIC Limited (SHA:601989.). Between January 2004 and January 2015, we count 31 transactions by the companies, for a combined total capital raised of $22.26 billion. Twelve transactions were by CSIC Limited, and nineteen by CSSC Holdings. Despite the initial public offerings of stock by CSSC in 2007 and CSIC in 2009, overall the companies have thus far issued much more debt than equity. To date, CSSC Holdings has raised a total of $8.63 billion from the debt markets and $3.02 billion from equity sales, while CSIC Ltd. has raised $7.04 billion from debt issuances and $3.57 billion from equity sales.

Figure 1. CSIC Ltd. and CSSC Holdings Capital Markets Transactions. Jan. 2004-Jan. 2015

Million USD

Sources: Company reports, Chinese media, Authors’ analysis

A series of policy guidelines implemented in the early to mid-2000s helped set the stage for private capital to enter China’s defense enterprises. In 2003, China Securities Regulatory Commission (CSRC) began tightly restricting related party transactions (including prohibiting various funds transfers) between listed subsidiaries and unlisted state-owned parent companies. This measure likely aimed to bolster investors’ confidence that they were buying more of a real asset and less of a shell company, which in turn would increase securitized assets’ potential value.

Then, in 2007, the Commission of Science, Technology, and Industry for National Defense (“COSTIND”) promulgated five guidelines to help defense industries prepare to securitize some of their assets. The policies sought to stimulate three core things: (1) allow non-public capital to enter the defense industry, (2) encourage the defense industry to make increased use of capital markets, and (3) encourage the defense industry to diversify investments and ownership. This improved environment for capital market investment likely accelerated the IPOs of CSSC in 2007 and CSIC in 2009. Soon thereafter, CSIC issued its first bonds in 2008, and CSSC quickly followed in 2009. From 2008 to 2011, CSSC issued $1.39 billion in bonds, and CSIC issued $2.93 billion.

Dissecting China’s Largest Military Shipbuilding Securitization to Date

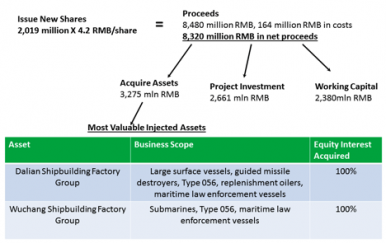

To give readers a more concrete sense for what a Chinese defense enterprise asset injection looks like in practice, Exhibit 2 breaks down the process CSIC went through in late 2013 and early 2014 to inject assets into its listed arm. First, the company sold 8.48 billion RMB (approximately $1.4 billion) worth of shares in a private placement. Second, it took 3.28 billion RMB (39 percent of the total raised) and devoted it to asset acquisitions. Finally, the company then injected the assets acquired from the state-owned parent company into the listed arm. CSIC stated that “the deal will expand the financing channels for China’s military defense. It would also herald an overall securitization of China’s military assets.”

Exhibit 2: Anatomy of CSIC’s USD $1.4 Billion Asset Injection Deal

Source: Company Reports, Chinese Media, Author’s Analysis

The asset injection brought two of CSIC’s three primary military ship construction assets—Wuchang Shipbuilding and Dalian Shipbuilding—into its listed arm (along with eight other assets). This confers more direct access to investors, especially those outside China. The injection also had a very positive effect on CSIC Limited’s rapidly depleting orderbook, as it brought more military business to the listed company. Indeed, China Securities Net reports that at the end of June 2014, CSIC Limited derived nearly 19 percent of its revenue from military goods (up from roughly 8 percent a year prior) and that the listed company’s military and marine engineering orderbook was 68 percent larger than a year prior.

Accessing Military Shipyard Assets Via Hong Kong

In November 2014, Guangzhou Shipyard International (“GSI”) purchased Huangpu Wenchong Shipbuilding from the CSSC parent company for 4.35 billion RMB, paying for the deal by issuing 271.6 million shares of stock to the parent and the balance in cash. Huangpu Wenchong is one of China’s key surface warship builders and has launched nearly 20 warships and large Coast Guard vessels in the past two years, including Type 054A frigates and Type 056 corvettes.

The Huangpu Wenchong asset injection opens a new, unique capital channel for investors interested in gaining exposure to the story of China’s naval modernization. This is because GSI is traded on the Hong Kong Stock Exchange, and is therefore much more accessible to foreign investors than CSIC and CSSC’s listed arms, which trade in Shanghai. GSI’s ability to access the A-Share domestic markets in China and the more foreign investor-oriented H-Share market in Hong Kong may turn out to be a major strategic advantage for raising capital.

CSSC to date has securitized a smaller portion of its asset base than CSIC has. However, GSI’s statement to the Hong Kong Exchange disclosing the Huangpu Wenchong deal suggests CSSC views greater securitization of its military shipbuilding assets as a core strategic priority that will help it “…enhance protection for military construction assignments through means such as financing from the listing platform, so as to exert the supporting function of the capital markets towards the development and growth of military enterprises.”

CSSC management’s decision to inject assets into a vehicle traded in Hong Kong strongly suggests that China wants to make its military-industrial complex more accessible to potential investors from around the globe. If non-PRC investors meaningfully buy into GSI, we would expect this to drive CSSC to make future injection assets available on the Hong Kong exchange as well.

Who Is Buying Shares So Far?

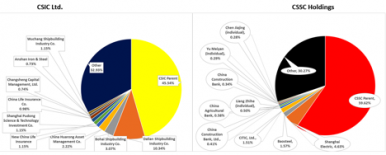

The companies disclose their 10 largest stockholders and the percentage of the enterprise’s shares that those parties own. For CSIC Ltd., as of 3Q2014, approximately 2/3 of shares are owned by strategic investors, led by the CSIC state-owned parent, which controls approximately 45 percent of shares (Exhibit 3). Roughly 70 percent of CSSC Holding’s shares reside with strategic investors. For both CSIC Ltd. and CSSC Holdings, the 30-33 percent of shares not held by the parent company or large strategic investors such as life insurance companies, banks, and steelmakers are the “free float” that at least in theory can be purchased by private investors in China or by foreigners qualified to trade in Shanghai.

Exhibit 3: Shareholding Structures of CSIC Ltd. and CSSC Holdings

Percentage of total shares

Source: Company Reports, Authors’ Estimates

To the best of our knowledge, CSSC and CSIC do not publish the identities of initial buyers of their debt issuances or private placements of equity (such as those which CSIC and Guangzhou Shipyard International have used to fund asset injections). There also does not appear to be much data on how the companies’ bonds have traded on the secondary (or retail) market. Some economists analyzing China’s corporate bond market overall have concluded that secondary trading activity is limited because while private investors can, in theory, purchase corporate debt, commercial banks who initially purchase the debt tend to “hoard” it. At present, CSSC and CSIC’s debt ownership is likely concentrated between a relatively small number (perhaps 25-50) strategic investors dominated by banks and insurance companies.

Strategic Outlook and Implications

Further securitization will likely boost the volumes of capital CSIC and CSSC can raise. The companies’ listed arms have already proven to be a formidable fundraising force. Allowing investors to gain exposure to more of the companies’ prime assets will likely enhance domestic and foreign investors’ appetite for debt and equity issuances. A key question here is, “what assets might be injected into listed companies next?” One CITIC Securities analysis views research institutes within CSIC and CSSC as a possible next target. However, the government’s priorities and those of investors diverge on the research institute question. The government wants to get these institutes off the official balance sheet, while investors seek productive assets likely to yield better economic returns.

Deals that inject shipbuilding assets such as Hudong Zhonghua and Jiangnan Shipbuilding into publicly traded entities are much more plausible. The GSI/Huangpu Wenchong transaction in November 2014 marked a turning point in the relationship between China’s state shipbuilders and the ability to raise money through capital markets specifically for military modernization. Former CSSC chairman Hu Wenming noted that this deal “broke through regulatory restrictions and opened the pathway to securitization for the military product and general assembly industry or rather for security assets.” He expects that many more military industrial assets will be securitized.

The shipbuilders’ greater access to the domestic and global capital markets will not replace defense budget funding, but can augment it to a degree that will facilitate significant additional naval modernization activity without a commensurate burden on the national balance sheet. The issues analyzed here therefore have important political and national security implications.

Consider some plausible scenarios that could arise as China’s shipbuilders more market-based sources of funding, including foreign investors:

- How would policymakers react if U.S.-domiciled investors purchased a major debt issue by CSSC Holdings or CSIC Limited that was in part earmarked to upgrade military ship production capabilities?

- What if a European or Canadian pension fund participated in such a transaction?

- What if investment banks with major U.S. ties helped CSSC or CSIC raise funds that, due to the fungibility of money, effectively helped underwrite part of China’s naval buildup?

As China’s defense enterprises pursue additional resources from the capital markets, international investors will also likely seek to buy into deals, as opposed to simply brokering them. For example, major global investment banks Barclays, Société Générale, and ANZ facilitated a 500 million euro bond sale by CSSC Holdings in February 2015.

China’s equity markets are currently in a period of significant uncertainty, as Beijing tries to find its feet after heavy state involvement failed to quell two major stock market downdrafts over the past six weeks. That said, Chinese military shipyard assets will very likely be attractive to investors because China’s naval hardware budget is poised to continue growing strongly for at least 5-7 more years. Moreover, the military yards get the most skilled staff and have a virtual monopoly on supplying warships, subs, and parts to the world’s aspiring naval superpower.

China’s naval buildup is now coming to a stock exchange near you. It is very plausible that investment transactions with Chinese shipbuilders which pass formal legal muster may in fact still engender substantial diplomatic and security consequences. For this reason, China’s military shipbuilders’ turn to the capital markets deserves serious and prompt discussion in Washington, Tokyo, Canberra, Seoul, Singapore, and other capitals.

Gabe Collins is the co-founder of China SignPost and a former commodity investment analyst and research fellow in the US Naval War College’s Maritime Studies Institute.