We now see that all this summer’s talk about a resurgent Shanghai Cooperation Organization (SCO) was at least premature, if not enduringly overoptimistic. Earlier this month, the presidents of the leading Eurasian countries held important leadership meetings in Beijing on the occasion of the Chinese military parade to mark the 70th anniversary of the end of World War II. Tellingly, not even the Chinese hosts, traditionally the SCO’s main boosters, highlighted the institution’s supposedly new momentum following its mid-July leadership summit in the Russian city of Ufa.

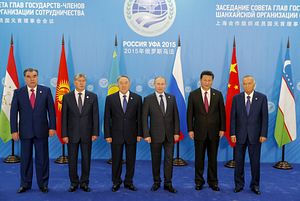

The July 9-10 decision of the SCO Heads-of-State Council to, in principle, expand the institution’s roster of full members to include India and Pakistan was admittedly newsworthy. For more than a decade the SCO had been deadlocked over the enlargement issue. The same six countries that founded the SCO in 2001 – China, Russia, Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, Tajikistan, and Uzbekistan – are still its only full members, despite the growing number of formal observer countries, “dialogue partners,” and other SCO affiliates and aspirants seeking that status.

Although the SCO has tried to enhance the status of non-members, there is no evidence that these other states have benefited much from their lesser status. Only full members can exploit the SCO’s consensus-based decision-making to veto SCO activities, which they do by calling for further studies. The limited value of anything less than full membership has been evident in the case of Turkey, which welcomed its accession to formal dialogue partner in 2012 but has not even bothered to send high-level officials to the SCO annual leadership summits or other meetings.

At the time of the July summit, Sun Zhuangzhi, the secretary general of the Shanghai Cooperation Organization Research Center of the Chinese Academy of Social Sciences, joined many local experts in rejoicing in the formal end of the protracted expansion gridlock. In his words, “with the expansion of its membership, the increasingly consolidated regional organization will be able to assume more responsibility for global stability and prosperity.” Russian President Vladimir Putin boasted that a dozen countries without a current SCO affiliation want one.

India and Pakistan

For both Beijing and Moscow, allowing both India and Pakistan to enter simultaneously was a sensible compromise. Russia has traditionally been a strong economic security partner of India, while China has been a strong backer of Pakistan. In recent years, however, Russian-Pakistani ties have improved, with Russian diplomats no longer calling Pakistan a potential failed state that could present a more serious threat to Russian security than Iran. Russian-Pakistani defense ties are also expanding to include major arms deals and detailed dialogues on regional security issues.

Explaining Beijing’s shift regarding New Delhi’s SCO aspiration is harder since the China-India relationship remains troubled due to unresolved border disputes, Beijing’s unease over New Delhi’s defense ties with Washington and Japan, and Indian irritation at China’s support for Pakistan’s nuclear aspirations and blind eye towards Pakistani-linked terrorism in India. Beijing is still blocking New Delhi’s admittance to the Nuclear Suppliers Group and Indian dreams of becoming a permanent member of the UN Security Council.

Most likely, Chinese leaders decided that letting India have full SCO status was a harmless gesture to win favor with host Putin, who desperately wanted his back-to-back SCO and BRICS summits at Ufa to appear as major successes. Thanks to its decades-long regional economic surge, Beijing has little to fear from an expanded Indian presence in Central Asia. China’s unassailable economic supremacy in most of the region will only grow in coming years thanks to Russia’s economic difficulties and Beijing’s seemingly unstoppable “One Belt, One Road” initiative to integrate the Central Asian economies with each other and with China. Because of physical barriers and its technological and financial limitations, India is in no position to compete with China anywhere in Eurasia.

Moreover, despite all the publicity surrounding the formal invitation to become full SCO members, neither India nor Pakistan is likely to attain that status anytime soon. The elevation of Iran, Mongolia, or any other aspirant to full membership will take even longer due to residual worries among the Central Asian governments as to how Washington would view Tehran’s promotion and Chinese and Russian distrust regarding Mongolia’s quest for trans-Pacific ties with the United States. The SCO governments, jealous of their sovereignty, have long been divided over membership enlargement as well as the organization’s functions, authorities, and collective policies.

As Beijing knew, Uzbekistan now replaces Russia as the one-year rotating chair of the group. Its president, Isam Karimov, who attended the Beijing parade, has continually resisted the development of strong multinational post-Soviet institutions. Following the Ufa summit, Karimov insisted that the India-Pakistan membership issue remain under review and proceed in a way that does not weaken the SCO. He has also laid down a marker that the SCO must not become an anti-Western tool of Beijing and Moscow. Other Central Asians likely share Karimov’s concern that, were India and Pakistan to become full members along with Russia and China, the influence of the other full members would substantially diminish.

Internal Strains

Although the eventual full membership of India, Pakistan, or other states could impart new momentum to the SCO, the move could also deepen internal strains within the organization and make it less coherent and effective. With Nepal and Sri Lanka already formal dialogue partners, adding India and Pakistan would make it impossible for the SCO to address South Asian security and economic issues, which as American diplomats have learned through their thwarted Central-South Asian silk road initiatives are fundamentally different from the Central Asian questions that have dominated the SCO since its founding. The existing six member states alone already have major differences in their geographic and population size, their military power, and the economic resources that they bring to the SCO. It would be a gamble to presume that the additional assets brought to the SCO through membership growth would outweigh a further widening of these differences.

Some observers hope that giving India and Pakistan full membership would make it easier for these two countries to resolve their differences regarding Afghanistan and Central Asia, but the most likely consequence of elevating them to full membership would be to add to the existing rivalries between Beijing and Moscow and between Tashkent and several other members. Pakistani Prime Minister Nawaz Sharif and Indian Prime Minister Narenda Modi held their first bilateral talks in more than a year at Ufa and committed to resume their bilateral dialogue. This initiative, like so many others launched at the SCO, has since stalled as India and Pakistan relations have retrograded. Although the decision at Ufa to give Afghanistan and Armenia dialogue partner status might provide these rivals another forum with which to resolve their territorial dispute, there is no evidence that China or other SCO governments besides perhaps Russia want to entangle themselves in the Nagorno-Karabakh issue.

For the most part, the SCO’s limited relevance probably will not adversely impact Eurasia’s economic and security situation. The organization does not normally sustain or even execute many of the agreements it reaches at meetings due to conflicting national regulations, laws, and standards, and the refusal of the members to supply the collective SCO bodies with many resources. The SCO members can readily identify and denounce what they oppose but have found it harder to sustain a positive and proactive agenda. Chinese efforts to promote a “Shanghai Spirit” has not caught fire beyond Beijing. The organization’s economic structures are especially feeble in comparison to the other multinational institutions active in the post-Soviet economic space.

These other Eurasian institutions have started their lives later than the SCO but have been developing more rapidly. Whereas last July’s summit saw no tangible progress in building the SCO’s economic institutions, the concurrent BRICS meeting marked the formal launch of that group’s New Development Bank, while China has launched its own Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank and adopted and revitalized the Kazak-created Conference on Interaction and Confidence Building Measures in Asia (CICA), which some Chinese aim to make into an influential pan–Eurasian security structure that excludes Japan and the United States. It would prove hard for the SCO to sustain forward momentum without a strong Chinese commitment.

The SCO Development Strategy adopted at Ufa challenged Western values and demanded respect for cultural-civilizational diversity, but the SCO governments have many other opportunities to make this critique, which is not supported by India or Mongolia. Russia and China do not appear to treat the other SCO members any differently from their other non-SCO partners, raising the issue of whether post-Soviet Eurasia would look any different if the SCO did not exist.

Even as an empty shell, the SCO would be able to continue its basic function of reassuring Beijing and Moscow about one another’s intentions and activities in Central Asia. China makes sure to describe most of its major economic and security initiatives in the region, including loans, as occurring within the SCO framework even when these acts are essentially bilateral. Moreover, Beijing has not challenged Moscow’s security preeminence in the region, which Russia maintains through the independent Collective Security Treaty Organization (CSTO), which includes all SCO members except for China. Meanwhile, Russia uses the SCO both to signal its acceptance of China’s growing activities in Central Asia as well as to monitor them. Moscow is keeping its institutional options open by building a Eurasian Economic Union that could dilute, if not contain, China’s economic presence in Central Asia.

Terrorism

However, there is one area where the SCO could do some real good. SCO leaders have been trumpeting a growing regional security threat from the Afghan Taliban, al-Qaeda, and most recently the Islamic State, which has recruited thousands of SCO nationals. At Ufa, the SCO members appealed to the United Nations to direct more efforts against terrorism, extremism, and narcotics emanating from Afghanistan. The continued fighting in Afghanistan has prevented China from encompassing that country in its regional integration and natural-resource importation plans.

Despite this threat and the SCO’s counterterrorism focus, the organization has made no noticeable contribution to Afghanistan’s security. If anything, its members’ divisions regarding the Afghan issue have grown even after Afghanistan became a formal SCO observer in 2012. China has engaged in some limited diplomatic initiatives to reconcile the Kabul government with the Afghan Taliban and the Pakistani security services, while Russia and some Central Asian countries are pondering how to use the CSTO to counter Taliban-related threats. Thus far, no SCO member has tried to use their organization as a major tool to address Afghan security issues.

As a result, the SCO has confined its security activities north of the Afghan border to making alarming collective statements, sharing intelligence about drug trafficking and Afghan terrorists, and conducting intermittent joint counterterrorism training exercises. It has been the CSTO that has taken the lead in trying to prevent terrorists and narcotics from entering Central Asia from Afghanistan, while NATO, even with less than a tenth of the forces it had previously had in Afghanistan, still provides most of the foreign equipment and training to the Afghan National Army. Even in the economic field, the SCO has not provided much assistance to the Afghans, despite the enormous resources available to China and Russia.

The SCO could more effectively achieve its goals in Afghanistan if the organization helped develop that country’s legal economy and lowered trade barriers between SCO members and Afghanistan, which have contributed to the ridiculously small volume of two-way commerce between them. While certain barriers are for understandable security reasons – preventing terrorists and narcotics traffickers from moving across the frontiers – the SCO could establish a small number of special border zones, with preferential custom and simplified visa regimes but also intensified security monitoring to block illegal transit. They could also finance Afghan-led development projects and include Afghanistan in the infrastructure projects that they are building across the Central Asian landscape. Among other benefits, these measures would help Kabul manage the declining external assistance Western governments will likely provide in coming years.

Building new joint coordination and funding mechanisms to assist Afghanistan would give the SCO sorely needed collective institutional capacity separate from that of its member governments. The SCO has yet to develop institutional mechanisms to fund major economic reconstruction projects It would also help keep the organization relevant and make a genuine contribution to international peace and security.