Nepal’s new constitution is its seventh iteration since 1950. Promulgated on September 20, 2015, the new document, which came into being after seven years of grueling effort, was supposed to be a representative document, at last compared to the previous six. However, it is proving to be as contentious and controversial as any of the past ones. Prashant Jha, a journalist who has followed Nepal’s recent evolution into a democratic republic from up close, expresses serious doubts about the inclusiveness of the constitution and its capacity to bring representative democracy to Nepal.

Author of the seminal book on Nepal, “Battles of the New Republic,” Jha spoke with The Diplomat, outlining his deep apprehension about the new constitution.

The Diplomat: Is Nepal’s new constitution a step forward or backward?

Jha: Nepal has had six constitutions so far and the problem in Nepal has not been writing the constitution but the ownership of constitutions. All the previous constitutions have not been owned by all sections of the society and all political forces. These constitutions have not been sustainable. Of course, there is a qualitative difference between the old ones and the new one. Previous constitutions were written by monarchs, but this has been written by elected people in the constituent assembly (CA). That is a positive difference.

The idea was that the CA would be a platform where people from the diverse social groups of Nepal would sit together and collectively participate in drafting a document and would have the same common rules for all. The idea was that the CA would bridge and overcome the social and ethnic divisions existing in Nepal. The idea was that the CA would create a political structure where different ethnic groups and social groups, particularly excluded ones, would get to exercise power and be a part of more inclusive order. Based on these principles, the CA has failed. It is a setback because the constitution is not owned by a substantial section of the country.

The Terai region in southern Nepal has been on strike for the last 40 days. The socially marginalized groups, like the Madhesis, who live mostly in the Terai area, Janajatis (indigenous people), and women have strong objection to the provisions of the constitution. They feel left out. So the constitution is not collectively owned by a large section of the citizenry. It represents a setback. It is not only the ownership, but also the process through which the constitution has been adopted that is questionable. The entire process has been hijacked by a few leaders, all belonging to the upper caste communities.

The CA was supposed to create inclusion and provide political access to marginalized social groups, but what has happened instead is that the constitution has been framed and political boundaries have been redrawn in a way that ensures the dominance of the traditional political elites: the upper caste people of the hills. It dilutes the principles of affirmative action and reservation. So to summarize: the CA represented a historic opportunity for Nepal, but what we finally landed up with is a lost opportunity.

Why you think that the three major parties rushed to pass the constitution?

It is inexplicable behavior if you go by rational calculations. These parties have been sitting together and writing the constitution for the last seven years; one wonders what was the immediate rush. The parties argue that the earthquake expedited the process. They say that they wanted to focus on reconstruction, but this is a claim that belies credibility. For the last four months, not a single task has been accomplished on the reconstruction front. The international treasure made available for reconstruction has not been used at all, and the parties have done little on the reconstruction front.

I think it is an excuse rather than a real reason. The real reason is convergence of the power ambitions of the leaders belonging to the three major political players in Nepal. Prime Minister Sushil Koirala aims to become the President of Nepal and leave a legacy. The leader of the second biggest party, the United Marxist Leninists (UML), Khadga Prasad Sharma Oli, wants to be a prime minister, and Maoist leader Pushpa Kamal Dahal, known as Prachanda, who is a marginal political player right now, sees an opportunity to leverage power in Kathmandu and further wants to insulate himself from any probes into his alleged financial corruption. Another Congress leader, Deb Bahadur Deuba, thought that he could become party president if the process is pushed through. Therefore, it is this convergence of power ambitions across various parties that explains the haste in constitution making.

So if one goes by your analysis, the new constitution does not guarantee stability in Nepal?

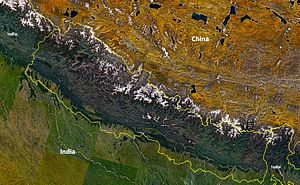

The constitution, by alienating the Terai, has introduced instability from the word “go.” The people in the area have close linguistic and ethnic ties with people across border in Bihar and Uttar Pradesh in India. These are the people who have felt deeply alienated by the hill-dominated political structure. We have seen many such ethnonationalist movements taking a different kind of political shape across the world. The Nepali political elite has played with fire in ignoring and alienating the Terai.

Why did Nepal refuse to heed India’s advice and went ahead with the constitution despite New Delhi’s objections?

The fact is that India has been consistently telling Nepal for the past year to write a constitution based on consensus, a document that represents the aspirations of all sections of the society. In the past weeks, we saw the foreign minister issue a statement, the Indian foreign secretary, S. Jaishankar, going as Prime Minister Modi’s special envoy. We also saw the Indian ambassador in Kathmandu making public pronouncements. Despite all this, we saw that the Kathmandu-based political elites went ahead. They are actually trying to consolidate the power of the politically dominated communities and that became their primary political consideration.

They did not listen to Indian advice because, at the core, they just want to entrench elite power in Nepal. We have seen in the past when it comes to these kind of base political calculations external actors cannot play greater role. It is an internal balance of power which was in the favor of the upper caste groups. Another reason is the shared ambition. The ambition of various parties has come together; they all realize that they are in the same boat and they have their own political aspirations. This is more important than any Indian advice. Third, India reacted a bit late. It should have woken up to the crisis earlier. We know that the Indian embassy in Kathmandu was reporting on developments there on a regular basis. I think there was a bit of an absence of attention at the higher bureaucratic and political levels in Delhi. By the time India reacted, events had already unfolded in Nepal.

So this constitution won’t be sustainable?

This constitution, in the current form, is not going to sustain for long.This document has to go through substantial review to hold for long.

This interview has been edited for brevity and clarity.