The Japan Innovation Party is splitting, with party president Yorihisa Matsuno recently expelling twelve members close to party founder Toru Hashimoto. The split is not over policy, but strategy. Matsuno and most of his party seek closer cooperation with the Democrats, Japan’s largest opposition party; while Hashimoto and his supporters prefer to remain independent, but close to the ruling Liberal Democrats. The Innovation Party is Japan’s third largest, so this split could lead to the revival of the Democratic Party, a return of competitive elections, and a shift toward pro-market policies.

Why the split? Local politics. Hashimoto is the mayor of Osaka and founded a strong local party in 2009, which he used to help launch the Innovation Party in 2012. As a result the party is semi-regional – able to win nationwide, but only win reliably in Osaka. This created an Osaka faction whose members are secure in their seats and imbued with local Osaka politics (where Hashimoto’s local party and the Democratic Party are quite antagonistic). Members outside of Osaka though, are often isolated: few share the same prefecture, and fewer receive strong support from local politicians. Merging with the Democrats would solve both problems, and now they are free to do that. Moreover, Matsuno was formerly a leader in the Democratic Party, so he certainly has the connections necessary to pursue a merger. The question is: What will the Democratic Party under Katsuya Okada do?

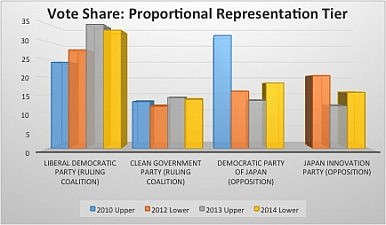

Okada knows his party is in poor shape. Between the 2010 and 2012 elections, the party’s support dropped by half – much of it going to new parties like Japan Innovation. It has hardly improved since then. The party is no better in local politics: It nominated 40 percent fewer candidates for local elections in 2015 than 2011. A merger could go a long way to helping the Democrats recoup its losses by removing a competitor, replenishing their stock of quality candidates, and offering a rebranding opportunity.

Mergers though, are not costless. They create new sets of winners and losers, and nobody wants to be a loser. In this case, neoliberal reformers stand to win as they are joined by many like-minded politicians from Japan Innovation; while old socialists and traditional conservatives stand to lose out. Members of these last two groups could make trouble. A likely alternative would be to hedge by forming an alliance for the 2016 Upper House elections. If successful, Okada would have a much easier time pursuing a merger prior to the more consequential Lower House elections (likely in 2017 or 2018).

The Democratic Party could forgo cooperation, but a merger or hedge is most likely. Forgoing cooperation would mean a continuation of the status quo: Liberal Democratic victories. Moreover, compared to when the Democrats merged with the Liberal Party in 2003, the incentives to merge are stronger: The 2003 Liberal Party was not as strong as today’s Innovation Party; while the 2003 Democratic Party was stronger than today’s Democratic Party. Finally, Okada would likely welcome the policy changes brought by a merger – he was previously party president in 2005, a time when the Democrats pushed pro-market policies similar to those espoused by the Innovation Party.

Turning instead to Hashimoto and his followers, they are already in the process of forming a new national party. Although unlikely to be as successful as the Innovation Party was in 2012, they stand to be a formidable regional party with some reach beyond Osaka. However, the party may be pulled to align with the Liberal Democrats. Japanese Prime Minister and Liberal Democratic Party President Shinzo Abe has been astute in courting Hashimoto and his supporters. If successful, his party could dominate politics in Japan’s second largest metropolitan area.

This split has presented the Democrats with an opportunity to recoup its 2012 losses, and the Liberal Democrats with an opportunity to dominate Osaka politics. However, pursuing these opportunities would pull both parties toward more pro-market policies. If the Democrats are successful, they will present a far more formidable challenge to the Liberal Democrats than they have for the past three years. Whether these parties will respond to renewed competition by raising their game or playing dirty is another matter – there are certainly precedents for both.

Christopher Pearson is a PhD student at the University of Washington’s Henry M. Jackson School of International Studies. His research is on electoral cooperation in Japan. He holds an MA in East Asian Studies from New York University and a BA in Philosophy from Trinity College. He has previously lived in Japan, Korea and Taiwan.