A look back at the year’s headlines and ten months of weekly reflections on U.S.–China relations might suggest a rising rivalry. In reality, however, 2015 was the year longstanding tensions went public, in no small part due to changes in U.S. policy.

In areas of disagreement with China, the U.S. government slowly and methodically increased pressure on Chinese counterparts, gradually defining and threatening action against Chinese activities deemed to be objectionable.

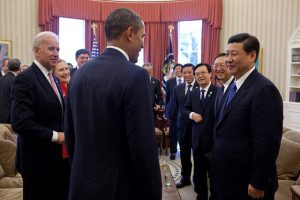

Concrete areas of bilateral cooperation also went public this year in a very different way. After President Barack Obama and President Xi Jinping committed in November 2014 to work together toward a global deal on climate change in Paris, the two governments publicly emphasized their alignment, and they deserve significant credit for the positive outcome this month.

Even as public disagreement has proliferated over strategic issues at sea and in cyberspace, China was a full member of the group that reached the Iran nuclear deal; U.S.–China military exchanges have maintained momentum; and new protocols for unplanned military encounters have reduced the risk of accident or miscalculation.

But feel-good cooperative efforts are naturally likely to be made public. More consequential this year has been the persistent publicity around two prominent areas of difference—maritime security and cyberspace—where much news had previously remained in the shadows.

Public pressure and dueling ambiguities in the South China Sea

The United States and China are structurally inclined toward disagreement in maritime disputes. Two U.S. treaty allies, Japan and the Philippines, are engaged in territorial disputes with China, and U.S. concepts of global security rub up against Chinese ideas of national security. In the South China Sea, 2015 brought an apparently concerted effort by U.S. officials to publicly expose and directly challenge Chinese conduct.

Much of the U.S. effort occurred in the context of anonymous quotes from U.S. officials, anticipating or advocating for the U.S. military to directly challenge implied Chinese claims through the longstanding Freedom of Navigation (FON) Program. Those anonymous quotes appeared as early as May. By August, anonymous sources were saying the Pentagon and the White House disagreed about whether or when to conduct FON operations. In October, the U.S. Navy sent a guided missile destroyer within 12 nautical miles of a disputed Chinese installation. Both governments maintained significant ambiguity in discussing that event, thereby keeping options open as the dispute continues.

What was not ambiguous was the U.S. decision to go public about China’s island construction and its practice of warning away planes and ships that travel nearby. In May, the U.S. government allowed a CNN correspondent to film and report from a U.S. spy plane flight, exposing to the world Chinese warnings about a legally ambiguous military zone. Non-governmental efforts by the Center for Strategic and International Studies to expose Chinese island construction were wildly successful in the media, providing repeated occasions for U.S. officials to comment.

Still, the U.S. and Chinese governments appear to be anticipating further moves. Later U.S. FON operations may be better documented. Chinese military warnings could be challenged as outside the regime of international law.

Most significantly, in 2016, the Philippine–Chinese arbitration case is expected to result in an award that China would legally be bound to respect, though the Chinese Foreign Ministry has repeatedly declared the proceeding invalid, and enforcement is based primarily on reputation.

Cyberspace, norms, and sovereignty

The U.S. government pursued an even more subtle escalation of public pressure on China over conduct and norms in cyberspace. In February, U.S. officials called out China for undermining the global internet in a Politico essay, focusing in part on domestic Chinese legal developments. In March, Obama added his voice in criticizing Chinese domestic rules that would require foreign companies to adhere to provide Chinese officials with security controls. In April, Obama signed an order putting sanctions on the table over “cyber activity” threatening U.S. security, including economic security.

It is perhaps no coincidence that the increasingly prominent Chinese concept of “cyber sovereignty” showed up in a draft national security law in May. If U.S. pressure can be interpreted as an attempt to enforce foreign norms in Chinese practice, especially domestic practice, sovereignty is the natural response.

By the lead-up to Xi’s visit to Washington in September, the massive-scale theft of U.S. government personnel files, unofficially attributed to Chinese state-sponsored hackers, had brought hacking and cyberspace to the front pages. Before the summit, the Obama administration made it known that the U.S. government was considering sanctions against Chinese firms connected with hacking incidents, and news stories suggested those sanctions could even come before Xi arrived. This public pressure reportedly resulted in a visit from Politburo member Meng Jianzhu, during which late-night meetings helped produce a real breakthrough in U.S.–China discussions about cyberspace.

That breakthrough, uncertain in its concrete implications, was one of bringing U.S.–China disagreements and common interests in cyberspace out into the open. The carefully worded pledge issued by both governments not to engage in, or knowingly support, online economic espionage took on unexpected weight when identical language was endorsed by the G20 leaders weeks later. Questions remain about implementation and follow-up from the September agreements, so it is still too early to declare a U.S. victory on the concrete issues. But it is hard to avoid the conclusion that U.S. public pressure achieved a diplomatic goal of opening bilateral channels on this increasingly troublesome set of problems.

In 2016, observers and officials both will have a better chance of assessing the success or failure of what could be a genuine bilateral commitment to confront cyberspace issues. The U.S. government maintains the threat of sanctions against Chinese firms, and U.S. observers are generally skeptical of vague reports that China’s government has taken action to address specific incidents. Nonetheless, new channels of communication are open, and the two governments continue to participate in the slow multilateral process of developing norms for cyberspace under UN auspices.

Primacy, preeminence, predominance, and politics

Looking ahead to the 2016 election and the ensuing transition, one of the most important developments of 2015 was a new serious public discussion about U.S. priorities in foreign policy, and specifically about whether the United States should continue to pursue “primacy” or “preeminence” in the Asia-Pacific.

A widely discussed study published by the Council on Foreign Relations argued that the U.S. should put “preeminence” first. Two top voices on China policy, David M. Lampton and Michael Swaine later separately questioned whether “primacy” or “predominance” is a wise or realistic objective for U.S. policy toward China.

China policy soul-searching in the United States may take on a more bellicose tone as the election overtakes political discourse in 2016, but with luck, that spirit of questioning assumptions and going public with uncertainty will fuel much-needed innovative thinking in the coming year.

Graham Webster (@gwbstr) is a researcher, lecturer, and senior fellow of The China Center at Yale Law School. Sign up for his free e-mail brief, U.S.–China Week.