South Korean President Park Geun-hye gave her annual New Year address and press conference on Wednesday. Coming one week after North Korea conducted its fourth nuclear test, Park’s remarks included a call for the “strongest yet sanctions” on Pyongyang – and for China, North Korea’s major international partner, to do its part to add to the pressure.

In her address, Park called for the UN to implement “bone-numbing” sanctions on North Korea. She warned that these sanctions must be “strong enough to change North Korea’s attitude” – something that clearly didn’t happen after the first, second, or third nuclear tests.

Park acknowledged that China has a major role to play in making sure this round of sanctions has more of an impact. “China has repeatedly said publicly that it would not tolerate North Korea’s nuclear weapons,” she said. “I think China is fully aware that if such strong will is not matched by necessary measures, we cannot prevent fifth and sixth nuclear tests by the North or guarantee real peace and stability on the Korean Peninsula.”

“Holding the hands of those in need is (the role of) best partners,” Park added. “I believe China will play a necessary role as a standing member of the U.N. Security Council.”

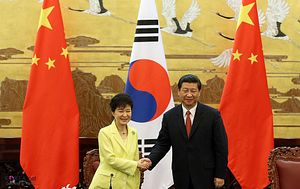

During her presidency, Park has made considerable outreaches to China, holding six summit meetings with her counterpart, Chinese President Xi Jinping. Most recently, Park traveled to Beijing to attend a military parade commemorating the 70th anniversary of the end of the World War II, an event the United States and its other allies mostly shunned. Beyond the obvious economic logic behind cultivating China-South Korea ties, Park’s administration was hoping that a close relationship with China would give Seoul more leverage to seek Chinese pressure on North Korea. But despite Xi’s proclamation that the China-South Korea relationship “has become the best-ever national relationship in history,” Seoul is not having much luck changing China’s traditional approach to North Korea.

Responding to Park’s address in a routine press conference, Chinese Foreign Ministry spokesperson Hong Lei told reporters, “[I]t is China’s consistent and clear position to uphold the international nuclear non-proliferation regime and oppose DPRK’s nuclear tests.” Yet he did not mention any specific steps China would take, including supporting UN sanctions. Beijing’s long-stated preference for dialogue – namely, a resumption of the Six Party Talks – over sanctions has not changed.

On January 7, a day after the test, Foreign Ministry spokesperson Hua Chunying called the nuclear issue “deep-seated and complex.” In phrasing that seemed to place equal blame on both Koreas, she said that the “reasonable concerns of all parties should be addressed through dialogues within the framework of the Six-Party Talks.”

“It takes two to tango. It takes six parties for the Six-Party Talks to work,” Hua added. “All relevant parties should return to the right track of resolving the Korean nuclear issue through the Six-Party Talks as soon as possible.”

This is the typical response from China, and it serves to implicitly validate North Korea’s claim that its nuclear program is necessary due a persistent security threat posed by the United States and South Korea (see also this op-ed run by China’s state news agency, titled “U.S. hostility behind DPRK’s nuclear brinkmanship”). That narrative has long frustrated Seoul, which chafes at being assigned part of the blame for North Korean provocations. As I wrote last week, history indicates China will agree to a tightened sanctions regime, but not one that goes far enough to actually squeeze the North Korean state.

It’s unsurprising that South Korea has been unable to change China’s calculus on the North Korea issues. However, what’s more disappointing is that high-level communication between the two sides was noticeably absent after the nuclear test. Hong, the Chinese foreign ministry spokesperson, said that “China and the ROK have been in close communication and coordination on the Korean nuclear issue and the situation on the Korean Peninsula.” Hong specifically mentioned conversations between both foreign ministers and the Chinese and South Korean officials in charge of the long-defunct Six Party Talks.

However, South Korea’s Chosun Ilbo points out that Seoul has not been able to get in touch directly with Xi Jinping. By contrast, Park had spoken with both U.S. President Barack Obama and Japanese Prime Minister Shinzo Abe the day after the nuclear test. Similarly, South Korean Defense Minister Han Min-koo has not been able to hold a conversation with his counterpart Chang Wanquan, despite a newly-activated defense hotline between the two sides.

Chosun also reports that, in the conversation between their foreign ministers, the two sides did not see eye-to-eye: “Foreign Minister Yun Byung-se repeatedly asked China to take strong sanctions against North Korea, but Chinese Foreign Minister Wang Yi stressed resolving the crisis through dialogue.”

Still, South Korea has another card to play in its attempts to persuade China to take a tougher stance: dangling the deployment of the U.S. THAAD missile defense system as a negative incentive. Beijing has repeatedly expressed its concern over a THAAD deployment, which China sees as a security threat. But in a press conference following her New Year’s address, Park said South Korea would review the THAAD issue based on its national security interests.