China’s central government has ordered local authorities to delay or cancel construction of new coal-fired power plants as regulators attempt to reduce a glut in capacity, just one year after decisions were delegated to the provinces.

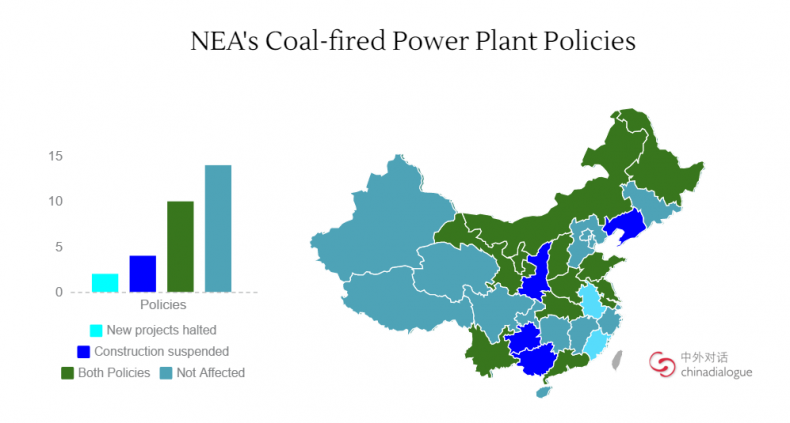

The National Development and Reform Commission (NDRC) and the National Energy Administration (NEA) have ordered a halt to construction of coal-fired plants in 13 provinces where capacity is already in surplus, including major coal producers such as Inner Mongolia, Shanxi, and Shaanxi. A further 15 provinces will be required to delay construction of already-approved plants.

Harsh punishments have been threatened for construction that goes ahead in breach of the new regulations. Operating licenses will be denied, connection to the power grid blocked, and financial institutions will halt lending to transgressors.

The curbs come as Chinese government departments are asked to make rapid policy adjustments in response to slowing electricity demand, as the country shifts toward a less wasteful and less energy-intensive economy and aims to reduce the amount of coal power generation.

China’s central government decided early last year to decentralize the authority to approve environmental impact assessments on coal projects starting from March 2015 onwards. But the problem goes back further, say analysts, pointing to the Chinese economy’s addiction to debt-fueled capital spending.

“The document shows the government has realized how serious the overcapacity issue is, and that decisive measures need to be taken to solve it,” Song Ranping, developing country climate action manager at the World Resources Institute (WRI), told chinadialogue.

“The government now needs to make sure this is implemented and evaluate how successful the measures are, so that controls can be further tightened if necessary,” he added.

Central and local governments need to address issues such as oversupply at an earlier stage, Song said. He pointed to the need for an “early warning mechanism” that flags up local decisions that exacerbate the surplus.

A clear price signal that a surplus of coal-fired power is uneconomic is lacking in China, because the country’s power tariffs are state-controlled. That means energy producers still receive a good price despite the oversupply.

The communique issued last week by the NDRC and the NEA comes in the wake of announcements made at China’s twin legislative sessions in March and in the country’s 13th Five-Year Plan, which placed a strong emphasis on greener, smarter economic growth.

To put this into effect the NDRC and NEA are imposing strict controls. Provinces with too much electricity are, in principle, not supposed to add extra coal-fired capacity; while those with power shortages are to give preference to non-fossil fuel generation and keep new coal-fired generation to a minimum. Thermal generating units that do not meet efficiency, environmental, safety or quality standards are to be gradually phased out. The measures will most likely apply to facilities that have operated for 20 years or more.

A sharp fall in the amount of hours that coal-fired power stations operate has underlined the major surplus in China’s electricity supply. According to data published by the NEA in January, the average coal-fired power plant was in use for 4,329 hours in 2015, a new 69-year low. The industry regards over 5,500 hours of operation as an indication that electricity is in short supply. Under 4,500 hours means an electricity surplus.

The NEA calculates that no more than 190 GW of additional coal-fired generation is needed before 2020, yet 300 GW of capacity has been approved or is under construction – far more than demand warrants.

Despite overcapacity and falling profits, enthusiasm for building new coal-fired power plants remains strong due to vested interests, the relatively high initial costs of renewable energy investment, and continued demand from industries that rely on coal power, such as cement, steel, base metals, and chemicals.

According to the CEC, 22.28 GW of new capacity was built in the first two months of 2016, 13.95 GW of which, over 60 percent, was thermal coal power.

This trend is clearly at odds with what China needs to do to meet its commitments under the Paris climate agreement, in which the world’s largest energy consumer has agreed to peak carbon emissions by 2030 or before. This will require a decisive shift away from coal and toward renewables, a transformation that will depend on China’s grid giving greater priority to solar, wind on the grid to displace coal, and augment hydro’s share of non-fossil fuel generation.

Feng Hao is a reporter in chinadialogue’s Beijing office.

This post was originally published by chinadialogue and appears with kind permission.