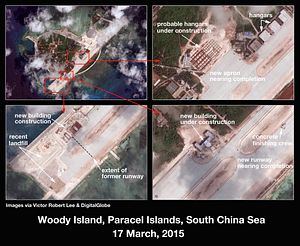

Last month, officials confirmed that China deployed advanced HQ-9 anti-aircraft missiles and fighter jets to Woody Island—one of several islands in the disputed Paracel chain in the South China Sea. The New York Times said the deployment “underscores the growing risk of conflict among the Chinese, their neighbors and the United States.” The Heritage Foundation asserted the move “makes clear that China is prepared to employ military forces to support its [South China Sea] claims.” Senator John McCain, chairman of the Senate Armed Services Committee, called the deployment “a blatant violation” of Chinese President Xi Jinping’s promise not to pursue regional militarization. And the Center for Strategic and International Studies’ Asia Maritime Transparency Initiative (AMTI) suggested the move foreshadows China’s militarization of its sites in the Spratly Islands.

Against this clamor came a rare attempt from the highest ranks of former- officialdom to correct the narrative that the move constituted a threat, escalation, or broken promise. Retired Admiral Dennis Blair was commander of U.S. forces in the Pacific during the 2001 collision between a U.S. EP-3 surveillance plane and the Chinese fighter jet sent to intercept it in the South China Sea. He was also President Obama’s first, if somewhat embattled, director of national intelligence. Writing in a Washington Post editorial, Blair argues that 1) the missiles deployed on Woody Island are not that militarily significant; 2) President Xi excluded Woody Island (where China’s claims are stronger than elsewhere) from his non-militarization pledge; and 3) the deployment is “self-defeating” because it motivates other regional claimants to cooperate against China.

Admiral Blair is correct. Concluding that the missiles and planes on Woody Island are a harbinger of future deployments or use-of-force in the Spratly chain exceeds the present facts expressly because President Xi’s non-militarization pledge excludes the Paracels. Speaking at the White House last fall, Xi said that “…relevant construction activities that China are undertaking in the island of South — Nansha [Spratly] Islands do not target or impact any country, and China does not intend to pursue militarization.” To be sure, intent can change with circumstances and a listener’s understanding of that intent can differ from the speaker’s. China may intend to militarize the South China Sea dispute and it may deploy weapons systems to the Spratly Islands in unambiguous violation of President Xi’s pledge. It may even use those weapons systems to enforce its claims against regional rivals. And if similar weapons systems appear on the Spratlys, it will tell us much more about how far China intends to move down that path. But these scenarios are no more likely today than before those missiles and aircraft appeared on Woody Island.

AMTI maintains a comprehensive catalog of impressive imagery and analysis of China’s construction and deployments in the region and believes the missiles on Woody Island indicate that China intends to emplace “…both an anti-access umbrella and a power projection capability” on the Spratlys. They suggest China’s next steps may be to harden aircraft shelters, place military radars and sensors, deploy missiles, ships, and aircraft to its features, and establish territorial baselines around the Spratlys (as they have for the Paracels).

The United States should remain especially vigilant about these indicators. Should China deploy missiles, ships, and aircraft to the Spratlys, this would signal an unmistakable escalation with troubling political implications. It would diminish, if not outright erase, hope of a diplomatic settlement to the territorial disputes in the South China Sea, and threaten that the aggressive but still bloodless regional competition may not remain so. However, as I have discussed, the fact that China has not declared territorial baselines around the Spratly Islands underscores its current preference to avoid an open clash over its South China Sea claims by keeping them ambiguous (in that, excluding the Paracels, they are nonexistent). Further, the problem with extending the Paracels analogy to the Spratlys now is that the militarization projects in the Paracels that China has replicated in the Spratlys are categorically different from the missiles and other weapons hardware appearing on Woody Island. Land reclamation, runway construction, and other infrastructure projects all enable military projection, but also have civilian use (even granted that such civilian utility alone does not justify the scale of China’s construction). Missiles and fighter aircraft do not. Suggesting the presence of the latter on Woody Island augurs their deployment to the Spratlys conflates dual-use projects like port facilities and runways with actual weapons systems merely supported or enabled by those projects.

Like President Bill Clinton’s famous parsing of what the definition of “is” is, much of the current analytical fracas centers on how you define “militarization.” Here it is critical to differentiate militarization from “weaponization”—specifically on land. Even setting aside China’s exclusion of the Paracel Islands from its pledge against militarizing the Spratlys, Senator McCain justifiably believes China’s infrastructure projects there and elsewhere constitute militarization because they can enable Chinese force projection in the region. That view is supported by unclassified assessments from the Director of National Intelligence (DNI) in response to inquiries from Senator McCain.

Viewing the South China Sea as a military problem, that assessment makes sense. A potential adversary’s intentions are assumed away when formulating contingency military responses. Instead, militaries plan against the capabilities they might face in a worst-case scenario, not intentions. However, this approach is not useful for understanding the political solutions that are still available short of armed conflict. While it is important to understand the military capability China could project in the Spratlys, it is not Pollyannaish to recognize that China has not realized this latent capability yet. The key sentence in the DNI’s assessment is this: “although we have not detected the deployment of significant military capabilities at its Spratly Islands outposts, China has constructed facilities to support the deployment of high-end military capabilities.” In other words, China’s ports in the Spratlys can support naval vessels, the runways can land military aircraft, and the radars (like the new facilities apparently constructed on Cuarteron Reef) can cue surface-to-air or anti-ship missiles, but there are no naval vessels, military aircraft, or missiles deployed there now. As long as there are not, the political options for peaceful resolution of the disputes—or at least the avoidance of military clash—are more viable.

China may be escalating its South China Sea activities to exercise greater effective control over the region and, as Blair acknowledges, any precedent of increased military presence there is concerning, in particular if that presence extends to the Spratly Islands in violation of Xi’s pledge. But as Micah Zenko, senior fellow at the Council on Foreign Relations, tweeted when the Woody Island missiles were revealed, “US conception of South China Sea ‘militarization’ refers only to weapons stationed on land, not on the actual Sea itself.” China already has extensive military capability in the region (as does the United States). Each of the handful of Type 052C and Type 052D -class destroyers believed to be assigned to China’s South Sea Fleet carries more HQ-9s than have been deployed on Woody Island. This is no doubt part of the reason neither Blair nor AMTI view the missiles on Woody Island as militarily game-changing.

But the difference between land-based and sea-based power is critical in the territorial disputes in the South China Sea. While navies can project power persistently, all ships must eventually return to port. Land power is permanent unless a deliberate effort is made to (re)move it, which can appear as a withdrawal or defeat. Land-based systems can certainly project influence during peacetime, but because they do not have room to maneuver on the region’s small reclaimed features, and because those features are isolated and geographically fixed, land-based systems there are quintessential “sitting ducks”—a vastly simpler targeting problem than ships at sea. In an open conflict, they are likely to be the first thing taken out, and so not actually that useful. Politically, however, they are much more potent precisely because they represent a permanent occupation and not simply a transient patrol. Further, the political cost of removing them, in terms of lost face, is likely to be prohibitive to a diplomatic settlement.

The Cuban Missile Crisis best illustrates this dynamic. In 1962, the prospect of nuclear missiles being based in Cuba sparked a global crisis between the United States and USSR. The central negotiation problem was the prospect of either side losing face by being seen to withdraw weapons systems already or soon-to-be in place that was only overcome by the risk of mutual destruction. But as the Cold War went on, submarines off each other’s coasts carrying greater numbers of more powerful nuclear missiles presented a much more immediate and complex military problem in theory, yet never generated the same immediate or consuming political crisis.

Naval and air power still represents the preponderance of military power in the South China Sea. But the particular political implications of land-based weapons systems there means the U.S. and other countries in the region have a special interest in monitoring their deployment and reinforcing peaceful norms with engagement and naval presence. Possession is nine-tenths of the law, so the adage goes, and as a practical matter it is hard to envision a South China Sea claimant giving up an island or feature they have garrisoned troops or emplaced armaments on.

In the Paracels, China can point to recognized Qing-era claims, a continuous civil and military presence since the 1950s, and spilled blood during a 1974 skirmish with South Vietnam. That history, no less the present militarized reality, makes the likelihood China would allow any part of the chain to revert to Vietnamese control through arbitration or diplomacy seem vanishingly small. The cases for sovereignty over the Spratly features are comparatively thinner and the environment lacks the same emplaced military presence for now. This makes it all the more important to keep them as free as possible of any claimant’s troops or weaponry for any non-military settlement to be realistic. That should be the focus before jumping ahead to an as-yet theoretical military problem.

Steven Stashwick is a writer and analyst based in New York City. He spent ten years on active duty as a U.S. naval officer with multiple deployments to the Western Pacific. He writes about maritime and security affairs in East Asia and serves in the U.S. Navy Reserve. The views expressed are his own. Follow him on Twitter. A version of this article has been published on the EastWest Policy Innovation Blog.