In a matter of weeks, perhaps even days, an international tribunal will pass judgement on some of China’s claims in the South China Sea. The judges could – potentially – rule that China’s “U-shaped line” is incompatible with international law. The implications of such a ruling will shake the region.

Before they can consider this question, however, the tribunal judges must first consider whether they have the necessary jurisdiction. Chinese officials have argued that the question of the “U-shaped line” is fundamentally a question of territory, about which the Permanent Court of Arbitration has no right to rule. However, new research tells us that the judges should ignore such arguments. Documents in China’s own archives prove that when Chinese officials approved the U-shaped line they never intended it to be a territorial boundary. Other evidence suggests that it only became one because of the intervention of an American oilman in the 1990s.

Despite many claims to the contrary, China has never made an official “historic claim” to all the water within the U-shaped line. It has asserted claims to the reefs and islands and to “surrounding” or “relevant” waters – but never spelled out their exact extent. In May 2009, Chinese diplomats attached a map of the U-shaped line to an official submission to the United Nations Commission on the Limits of the Continental Shelf but didn’t explain its significance. Until they do, no one can be sure what it actually means.

The most coherent formulation of what it might mean comes from Dr. Wu Shicun, president of the National Institute for South China Sea Studies (an organization jointly sponsored by China’s Ministry of Foreign Affairs and Hainan Province). For Wu, the U-shaped line claim contains three elements:

- sovereignty over the features within the line;

- sovereign rights and jurisdiction over water as defined by the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS);

- “historic rights” over fishing, navigation and resource development.[1]

The first two components: sovereignty claims over features (assuming that Wu is referring to rocks and islands rather than underwater reefs) and UNCLOS-based rights over waters surrounding those features are relatively uncontroversial. China’s neighbors dispute the extent of those claims but they are at least grounded in commonly-understood international law. The problem – for the region, for China and for the world – is the third part of Wu’s formulation. China’s legal scholars are working hard, but they’ve yet to come up with a convincing justification for China to enjoy “historic rights” to waters up to 1,500 km away from undisputed Chinese territory.

New evidence suggests they shouldn’t even bother trying. Thanks to the pioneering work of a Canadian researcher, we now know that the Chinese officials who drew the U-shaped line back in 1946-7 never meant it to be an historic claim to waters. It was simply a cartographic device to indicate which islands China claimed in the South China Sea and which it did not.

Christopher Chung, a PhD student at the University of Toronto, is the first person to forensically examine the archives of the official Republic of China (ROC) committee that drew the line. He has discovered that, “On September 25, 1946, representatives of the Ministry of Foreign Affairs, Ministry of the Interior, Ministry of National Defense, and ROC Navy General Headquarters 海軍總司令部 (NHQ) convened in the Ministry of the Interior to resolve several issues pertaining to the South China Sea islands.”

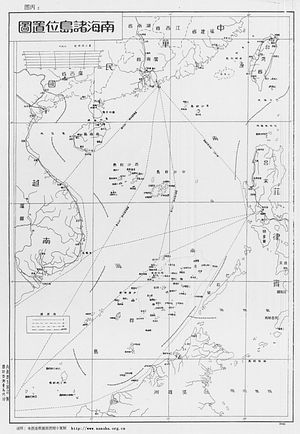

In its meeting that day, the committee defined which islands China would claim, according to a “Location Sketch Map of the South China Sea Islands 南海諸島位 置略圖” previously drawn up by cartographers in the Ministry of Interior. This map is the very first Chinese government document to show the U-shaped line and its meaning was clear to that ROC committee: it defined “the scope of what is to be received for the purpose of receiving each of the islands of the South China Sea” (“接收南海各島應如何劃定接收範圍案”). The committee’s interest was only in the islands. They made no mention of waters, historic or otherwise.

Nothing changed when that map was published a year and a half later. In February 1948, the ROC formally concluded four decades of internal Chinese arguments about where its borders lay with the publication of the Atlas of Administrative Areas of the Republic of China. The Atlas included the new official map of the South China Sea – the first public document produced by any Chinese government to include the line. Again, it was only about islands; there were no references to “historic rights.”

Nothing changed in China’s claim after the victory of the Communist revolution in 1949 either. When Zhou Enlai, premier of the People’s Republic of China, denounced the draft Treaty of San Francisco in 1951, he talked only of islands, not waters. The PRC’s 1958 “Declaration on the Territorial Sea” went further. While claiming a 12 nautical mile territorial sea, it explicitly noted that the islands were separated from the Chinese mainland by “the high seas.” There was no mention of “historic rights.”

The first maritime claims became more vague in January 1974, just before the Battle of the Paracels in which Chinese forces evicted Vietnam from the western half of those islands.[2] On January 12 that year, the People’s Daily declared that, “The resources of these islands and their adjacent seas also belong entirely to China.” But this was not a historic rights claim either. Rather it was the first sign that China understood the implications of the negotiations at the UN Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS), which had begun the year before: claims to maritime resources would be measured from coasts and islands. In mid-1973 the Republic of Vietnam (South Vietnam) had begun to auction off the rights to offshore blocks off its southeastern coast. China wanted a piece of that action.

The PRC participated in the UNCLOS negotiations from the beginning until their end in 1982. The final UNCLOS text, which it and all the other participants agreed to, makes no mention of “historic rights,” except in the very limited context of “historic bays” close to a country’s coast. China ratified the Convention in 1996, again without making any mention of historic rights.

So, the ROC government didn’t claim “historic rights” in the South China Sea in 1946-8 and neither did the PRC in its 1958 decree, its 1974 statement, at the UNCLOS negotiations, or subsequently in its 1992 Law concerning Territorial Waters and Adjacent Regions. Something changed in the 1990s, however. By the time the PRC passed its Law on the Exclusive Economic Zone and the Continental Shelf in June 1998, officials felt it necessary to include wording that, “the provisions of this Law shall not affect the historic rights enjoyed by the People’s Republic of China.”[3] The concept of “historic rights” only entered the official Chinese lexicon in the late 1990s: but why then?

While there were many factors at work in 1990s China, one that has been overlooked is the contribution of a buccaneering oilman from Denver, Colorado. In early 1991, Randall C. Thompson’s one-man oil company, Crestone, sealed a deal in the Philippines that opened his eyes to the potential riches of the South China Sea. Engineers with BP advised him that “the next big play” would be around the Spratly Islands.

In April 1991, Thompson traveled to the South China Sea Institute of Oceanography in Guangzhou. There he examined the results of Chinese seismic surveys the institute had carried out around the Spratlys since 1987. “They showed me some structures, I got excited about it and then I did some more research,” he told me. Thompson kept trying to persuade the Chinese to take Crestone seriously until, in February 1992, after much deliberation at the highest levels in Beijing, he finally got to pitch his proposal to the board of the China National Offshore Oil Company (CNOOC). Thompson took along a legal advisor to precisely define the patch of seabed he wanted the rights to: Daniel J. Dzurek, the former chief of the Boundary Division of the U.S. Department of State.

It was Thompson and Dzurek who persuaded the Chinese that they could make a legal case to exploit oil fields hundreds of miles away from China, off the southern coast of Vietnam. According to Thompson, “I used him [Dzurek] to help get validity to our concept this is Chinese waters and he strongly espoused many positions that this is Chinese waters, not Vietnamese waters based upon sovereignty of claim and historic stuff.” Dzurek, however, plays down his role. In an email he told me that he, “never gave China any ‘boundary advice’,” but “merely helped negotiate an offshore lease.” However in a key academic paper published after the Crestone episode, he noted that the Chinese term for the “U-shaped line” might best be translated as “traditional sea boundary line.”[4] He seems to have accepted – and developed – the idea that China had “historic rights” in the area beyond those spelled out in UNCLOS.

At the same time, lawyers in Taiwan, not mainland China, were also trying to develop the concept of historic rights. In 1993, the ROC government issued its South China Sea Policy Guidelines, which stated, “the South China Sea area within the historic water limit is the maritime area under the jurisdiction of the Republic of China, in which the Republic of China possesses all rights and interests.”[5] The phrase appeared in Taiwan’s draft Territorial Sea Law, but disappeared on the bill’s second reading in the Legislative Yuan.[6] The argument about whether or not to claim “historic rights” within the U-shaped line continues to divide Taiwanese maritime lawyers.

The concept has taken on new life in the Chinese mainland, particularly with officials such as Wu with an interest in maximizing the country’s maritime claims. This is no mere academic argument; the “historic rights” claim is the only possible basis for China’s auctioning of oil exploration blocks along the Vietnamese coast in June 2012: they are well beyond any potential Exclusive Economic Zone that could be drawn from land features claimed by China. It also lies behind the claims that Chinese fishing boats are operating in their “traditional fishing grounds” when they are found within Indonesia’s claimed EEZ off the Natuna Islands. Above all it provides the basis of China’s claim to have the right to regulate navigation within the U-shaped line – and obstruct “freedom of navigation” by other countries’ ships. This is the fundamental cause of the dispute between China and the United States in the region and the one most likely to lead their armed forces to come to blows.

The irony is that China seems prepared to risk conflict to defend a claim to “historic rights” that was first set out by an American boundary expert, and which is—at best—no more than 20 years old. Some have called for China to clarify its claims in the South China Sea. I argue the opposite. Imagine if Beijing clarified the claim in what the rest of the world would regard as “the wrong way” – stating that the U-shaped line is a boundary and all the waters within it are historically China’s. China would have nailed its colors to the mast and be forced to publicly defend its position, regardless of its legal and historical ridiculousness.

China has recently begun what it says is a five year process to draw up a new maritime law. Chinese officials and academics privately admit that there is still much confusion about what China should claim in the South China Sea and why. Some internal lobbies – such as Hainan Province with its large fishing industry – want to press a maximalist claim. But that claim will bring China into collision with its neighbors and the United States. Now is the time for China’s friends to explain that such a claim not only has no basis in international law, but also no basis in China’s own history. It is nonsense.

While that process of discussion continues, it is much better that China leave its claims vague and then quietly bring them into line with commonly-understood international law over time. Forcing China into a corner, in a legally adversarial manner, might sound attractive but there’s a risk that it could force the outcome least desired by the rest of the world.

Bill Hayton is associate fellow at the Asia Programme at Chatham House.

[1] Shicun Wu, Keyuan Zou Arbitration Concerning the South China Sea: Philippines Versus China, Routledge, 2 Mar 2016 p.132

[2] Chris P.C. Chung, Drawing the U-Shaped Line: China’s Claim in the South China Sea, 1946–1974, Modern China 1–35 (2015)

[3] Zou Keyuan, Historic Rights in International Law and in China’s Practice, Ocean Development and International Law, 32:149–168, 2001

[4] Daniel J. Dzurek, The Spratly Islands Dispute: Who’s On First? Maritime Briefing Vol. 2 No. 1, International Boundaries Research Unit, University of Durham, UK. 1996

[5] Quoted in Keyuan Zou ‘Law of the Sea in East Asia: Issues and Prospects’ Routledge, 2013 p.149

[6] Zou ibid p.47