According to a press release issued by the Permanent Court of Arbitration in The Hague, its verdict in the arbitration between the Philippines and China will be made public on Tuesday, July 12, 2016.

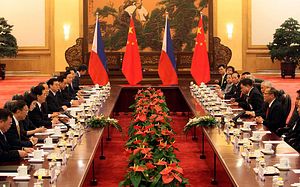

The Republic of Philippines v. The People’s Republic of China, the official name of the case, was initiated in January 2013 by the Philippines, following a difficult 2012 stand-off with China over Scarborough Shoal in the South China Sea.

The arbitration proceedings were initiated under Annex VII of the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS), the primary treaty governing international maritime law. Both China and the Philippines are party to the treaty, but Beijing has refused to participate in the arbitration, citing a lack of jurisdiction.

Last October, the Court announced that it had decided in the Philippines’ favor on the question of jurisdiction on most matters in the initial filing.

The Court ruled that the case was “properly constituted” under UNCLOS and that China’s “non-appearance” (i.e., refusal to participate) did not inhibit the Court’s jurisdiction.

While China has refused to participate in the proceedings, the Chinese government issued a position paper on the South China Sea in December 2014. That paper outlined China’s position on the issue of jurisdiction.

The highly anticipated verdict will have immediate geopolitical ramifications concerning the South China Sea disputes.

While the Court will not rule on the territorial sovereignty of individual features (a common misunderstanding of the purpose of the Philippines’ arbitration), it will decide the status of several disputed features in the Spratly Islands and elsewhere in the South China Sea.

The decision on the status of features, consequently, will have ramifications for the legal maritime entitlements that can be claimed under UNCLOS.

Under UNCLOS, maritime features receive varying entitlements based on whether they’re legally considered islands, rocks, or low-tide elevations. Islands receive the most capacious and generous entitlement: a full 200 nautical mile exclusive economic zone (EEZ), in addition to a 12 nautical mile territorial sea.

Rocks, by contrast, are entitled to a territorial sea of 12 nautical miles, but not an EEZ. Artificial islands, a subject of discussion since early 2014, when China started developing seven Spratly features into capable installations, receive no special consideration for maritime entitlements under UNCLOS.

Critically, there is a chance that the Court’s verdict could question or nullify China’s ambiguous nine-dash, or U-shaped, line claim in the South China Sea as having no basis in international law.

Beijing has justified its capacious claim in the South China Sea using the language of historic rights.

The Philippines and China are but two of six overall claimants in the South China Sea. Brunei, Malaysia, Taiwan, and Vietnam also claim various features.