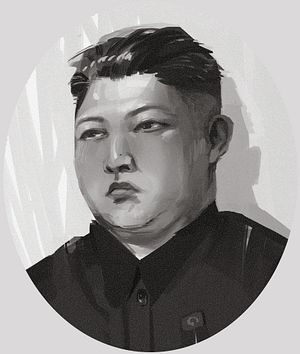

Last week, North Korea’s Supreme People’s Assembly met and proclaimed Kim Jong-un the chairman of a newly created Commission on State Affairs. The position, effectively a new title for Kim, the country’s third leader and supreme leader, was created by way of a constitutional amendment and, critically, replaces the all-powerful National Defense Commission.

Gauging something resembling political “reform” in Kim Jong-un’s North Korea hasn’t always been easy, but the substitution of the National Defense Commission is no small event.

As I’ve discussed here before, in recent months, Kim Jong-un has worked to implement his byungjin policy of simultaneously pursuing a nuclear deterrent and economic prosperity. The approach has been skewed toward the nuclear deterrent through 2016; Kim has tested what he claims is a thermonuclear device, shown off a compact nuclear weapon, launched a satellite, tested six Musudan intermediate-range ballistic missiles, shown off new solid-fuel engines, and more.

The economic leg of byungjin has played second fiddle. At North Korea’s much-anticipated 7th Workers’ Party Congress–the first event of its kind in more than 30 years–announced a new five-year economic plan, but nothing too ambitious.

The context of byungjin is important, however. Kim conceived of the policy as an explicit response to his father Kim Jong-il’s songun, or military-first, policy; songun caused widespread economic disaster and a famine through the late-1990s and early-2000s.

Kim had hinted at a head-on substitution of songun with his 2016 New Year’s address, which emphasized economic development while leaving nuclear weapons and the military on the margins.

With warnings in North Korean state media that famine is around the corner, the urgency of delivering on the economic leg of byungjin increases every day. (The UN Food and Agriculture Organization notes a 694,000 ton food shortage in North Korea this year.)

Replacing the National Defense Commission with a more even-handed body for political and economic state coordination sends a strong signal that Kim is looking to double down on economic work.

The Commission was set up through a similar constitutional amendment in 1998 under his father, becoming the ultimate executive authority within the North Korean state.

With his leadership largely consolidated five years into his tenure and demonstration of a likely capability to strike U.S. territory at Guam with the recent spate of Musudan testing, Kim can turn his attention to economic issues.

A possible coming shift in the second half of 2016 also makes sense when read together with North Korea’s attempts at rapprochement with China, its old ally and benefactor, in the wake of the exceptionally harsh sanctions enacted under United Nations Security Council resolution 2270. Most recently, Kim sent Chinese President Xi Jinping a congratulatory message on the 95th anniversary of the Chinese Communist Party’s founding.

The coming months will provide useful evidence in evaluating the extent to which we’re likely to see any real change.

Knowing North Korean unpredictability, instead of a turn to economic matters, we could get a KN-08 intercontinental ballistic missile test instead.