With less than a week before world leaders arrive for the Group of 20 Summit in Hangzhou, China is trying to stake out the high moral economic ground amid the heightened tensions in the South China Sea. Through its state-run media, China has recently urged India to focus on “preserving good economic ties” with China instead of “unnecessary entanglement” in the South China Sea dispute. As part of the effort to ensure the success of the September summit, China has also attempted to keep tensions with Japan in check. However, that is no easy task.

The August 15 anniversary of Japan’s surrender in the World War II occurred a month before the Summit. Every year, a couple of Japanese Cabinet members irritate China by visiting the Yasukuni Shrine, which honors convicted war criminals along with millions of war dead. The simmering row between the two countries in the South and East China Seas also drive bilateral relations away from peace. These longstanding disputes over the wartime history as well as maritime interests and rights have paved a difficult path for China-Japan relations. With the clock ticking fast before the September G20 Summit, managing China-Japan relations has become the biggest challenge to China.

Historical Disputes (Temporarily) in Check

Past annual visits by prime ministers and Cabinet members to the war-linked Yasukuni Shrine on August 15 have provoked outcries in China. This year, attention focused on a possible visit by Japan’s newly appointed defense minister, Tomomi Inada, who is perceived by some as a revisionist when it comes to Japan’s wartime history. On the day of Inada’s appointment, China expressed its dissatisfaction. Chinese official news agency commented on Inada’s assignment as one that would “draw the ire of Japan’s neighboring countries.” China had its reasons for concern. Inada has made trips to the Shrine for the past two years, as the minister in charge of regulatory reform in 2014 and the policy chief of the ruling Liberal Democratic Party (LDP) in 2015.

On August 4, when asked whether she would continue her visits to the Shrine, Inada evaded the question and said decisions on such visits are “a private, emotional matter.” Inada’s response did not exclude a possible Shrine visit. To some, it even increased the possibility of a visit as long as she regarded it as a “private” matter separate from her role as a defense minister. Unexpectedly, however, days before the August 15 anniversary, Japan’s Defense Ministry confirmed that Inada would not visit the Shrine. With Inada and Abe both staying away from the Shrine on August 15, this could be a success for China’s efforts to bring one of the disputed issues with Japan under control.

Maritime Disputes in Suspense

In contrast, the China-Japan maritime disputes have become unpredictable. While China’s activities in the South China Sea seem to have died down to prioritize the G20 Summit, China has renewed its push to assert its sovereignty over the Senkaku/Diaoyu Islands in the East China Sea in the past couple of months. Japan’s government recently lodged a series of protests with China after spotting an “unusually large number” of about 230 Chinese fishing boats, accompanied by six Chinese Coast Guard ships, in the waters around the disputed Senkaku/Diaoyu Islands. Tokyo also filed a protest against the presence of Chinese radar equipment on a natural gas exploration platform close to disputed waters (though they reportedly found the equipment in June) and urged Beijing to explain the purpose.

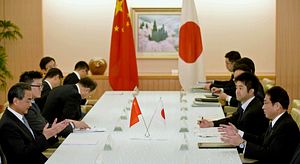

In his recent meeting with the Chinese ambassador to Japan, Cheng Yonghua, Japanese Foreign Minister Fumio Kishida warned that Sino-Japanese ties were “deteriorating markedly” as China was trying to “change the status quo unilaterally” in the waters surrounding the Senkaku/Diaoyu islands.

China’s increasing activities may reflect Beijing’s discontent about Japan raising its voice on the South China Sea disputes. As much as China intends to tone down tensions with Japan before the G20 Summit, Japan being vocal in the South China Sea issues has irritated China, which has repeatedly called on Tokyo not to interfere as it is not a claimant country in those disputes. Particularly after China’s humiliating loss in a court case brought by the Philippines, which challenged China’s sweeping claims to historical and economic rights in the South China Sea, Japan clearly expressed its stance on various occasions that it is important for the parties to the dispute to comply with the international tribunal ruling. Days after the ruling, Kishida conveyed Japan’s stance on South China Sea disputes to his Laotian counterpart, who chaired an Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN) meeting debating the issue.

Just when bilateral ties seemed to be in a downward spiral, an incident that saw Japan’s Coast Guard rescue Chinese fishermen has given China an opportunity to smooth ties with Japan before the G20 Summit. For the moment, China and Japan are trying to set their relations back on track, as the trilateral meeting between foreign ministers from China, Japan, and South Korea recently made an uncommon display of unity to condemn North Korea’s latest submarine missile test.

But the latest developments do not guarantee a forward-looking China-Japan relationship. The disputes over wartime history and maritime interests and rights are still outstanding and are expected to continue to be an obstacle to the improvement of China-Japan ties. To ensure the success of the G20 Summit, China’s biggest challenge is to put its tensions with Japan under control. Recently, Japanese Prime Minister Shinzo Abe has expressed a hope for a one-on-one talk with Chinese President Xi Jinping on the sidelines of the G20 Summit, but China has remained silent about its intent. Whether an Abe-Xi meeting will take place during the Summit, and if so, how it will turn out, will be a litmus test for China’s capability to manage its ties with Japan. Even more, a meeting will set the tone for China-Japan relations in the near future.

Emily S. Chen is the Silas Palmer Fellow with the Hoover Institution, a Young Leader with the Pacific Forum CSIS, and a Non-Resident Fellow at the Center for the National Interest. She holds a Master’s degree in East Asian Studies and a focus on international relations at Stanford University. She tweets @emilyshchen.