Over the past four years, ties between Beijing and Pyongyang under the leaderships of Xi Jinping and Kim Jong-un have been on a one-way trajectory: down. While Xi sent a delegation of advisors to Pyongyang shortly after taking office to deliver a personal letter to the North Korean leader, Kim’s welcome greeting to his new Chinese counterpart featured a satellite rocket launch in December 2012 followed by a nuclear test in February 2013 during the Chinese New Year and on the eve of Xi Jinping’s first National Party Congress. The provocations marked the first of many that have disillusioned the Chinese leadership (and people) about their fraternal brothers in the North. When Pyongyang tested its fifth nuclear test last week, after having already stolen the world’s attention from China’s G20 limelight by firing three ballistic missiles, it only added insult to injury.

Under Kim Jong-un’s regime, North Korea has dealt China a steady stream of irritants: the execution of Jang Song-thaek, China’s most trusted North Korean interlocutor; a fifth nuclear test and the development of a so-called hydrogen bomb; multiple long-range missile tests, despite senior Chinese diplomatic efforts to halt them; and the testing of a two-stage, solid-fueled ballistic missile most recently, which adds significantly to the North’s missile program’s capabilities. Even a Chinese leader more inclined to pursue stronger relations with China’s traditional ally would have had trouble justifying such efforts in light of these egregious actions.

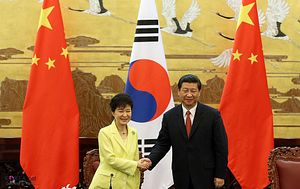

The course of China-South Korea relations over the same period, by contrast, has been nearly the inverse. Starting at a relative low point in bilateral ties following a deterioration of relations under the previous leaderships of Lee Myung-Bak and Hu Jintao, Xi Jinping and Park Geun-hye developed a palpable personal connection that lent momentum to a broader rapprochement. The leaders exchanged state visits to each other’s capitals in 2013 and 2014, despite the fact that Xi has not yet granted a meeting with Kim Jong-un. Both countries also advanced bilateral economic, trade, and commercial ties by signing a new free trade agreement in December 2015 and with South Korea’s decision to join the China-led Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank (AIIB). Park’s attendance at the Chinese military parade commemorating the 70th anniversary of the end of World War II – her sixth summit meeting with Xi — in September 2015 capped what some called a “tilt” by Park’s administration toward China.

Yet the embrace between Seoul and Beijing has not transferred to the strategic arena, where South Korea has long hoped that closer relations with China would produce greater coordination on the North Korea nuclear issue. Despite agreeing to “full and complete implementation” of UN Resolution 2270 following North Korea’s fifth nuclear test, Beijing has remained a reluctant partner in addressing nuclear proliferation by the Kim regime. For many years, China has watered down sanctions and draft resolutions against North Korea, and turned a blind eye to lackadaisical enforcement of those resolutions out of fear that such punitive measures by the international community could spark escalation or lead to regime collapse in Pyongyang, which China does not see in its interests. Moreover, China’s sustained economic engagement with the North, though not necessarily a violation of UN resolutions, undermines the effectiveness of multilateral sanctions.

The failure to make progress on addressing the North Korea nuclear issue has meant that the country’s nuclear weapons and ballistic missile capabilities have continued to mount. Thus, it was little surprise in July when South Korea and the United States jointly announced that they would deploy the U.S. defense system Terminal High-Altitude Area Defense (THAAD) by the end of next year in order to enhance South Korea’s capability to meet North Korea’s threat. U.S. leaders have emphasized to their Chinese counterparts that the decision to deploy THAAD was made “directly in response to the threat posed by North Korea in its nuclear and missile programs” and was “ purely a defensive measure… not aimed at any other party other than North Korea… nor capable of threatening China’s security interests.”

Beijing, however, views the deployment as part of a broader effort to encircle China in the Asia Pacific. Despite evidence to the contrary, China contends that THAAD would undermine China’s nuclear deterrent capability and that the existing Patriot PAC-3 missile defense system is capable of protecting South Korea from Pyongyang’s missile threats. China therefore sees the true aim of THAAD deployment to be China as well as Russia. South Korea’s cooperation with the United States on the system implicates Seoul in what China views as a U.S. subplot to establish a regional anti-missile system, enhance U.S. capabilities against Chinese strategic weapons, and undermine the overall strategic equilibrium in Asia.

Based on China’s assessment of the intentions of THAAD deployment and the threat it poses, the leadership in Beijing has begun to take retaliatory steps. China canceled several Korean pop concerts and television dramas in China, sending the stocks of some of the top entertainment companies into sharp decline. Chinese media reported on speculation that China had revoked visas for South Korean tourists visiting the Mainland. And the Chinese Air Force announced a possible move to enhance the capabilities of the country’s existing anti-missile capabilities. Foreign Minister Wang Yi summarized by saying, “the recent behavior from South Korea has undermined the foundation for our bilateral trust.” The end result could set back China-ROK relations to the lowest point in either leader’s tenure, despite the growing trust and cooperation that had been achieved.

A more extreme contingent of Chinese scholars has emerged in the aftermath of the THAAD announcement advocating that China not only take strong steps to punish South Korea, including sanctions on THAAD-affiliated Korean companies, services, and the politicians who actively supported its deployment, but also should also reevaluate sanctions against North Korea. They have proposed that the PLA should enhance China’s own anti-missile capabilities in order to minimize THAAD’s capabilities and deepen cooperation with Russia. For some in China, a reasonable response to South Korea’s deployment of THAAD would be to loosen sanctions on the North and look to repair and develop ties with Pyongyang.

It is misleading, however, to say that the deployment of THAAD now presents China with a zero-sum security dilemma in which it must choose between either safeguarding its security or advancing constructive relations with a South Korea that hosts a THAAD battery. This is a false choice.

The decision by the United States and South Korea to deploy THAAD in South Korea is a consequence of the collective failure to constrain Pyongyang’s nuclear ambitions, which threaten all countries in the region, including most certainly China. Pyongyang’s nuclear developments have offset Beijing’s efforts to safeguard stability on the Peninsula. Increasingly, North Korea is becoming a burden, even a liability, for China—eroding the benefits of the strategic buffer that it provides. The decision to deploy THAAD is a case in point. In the context of this significant setback for China’s North Korea policy and its regional diplomacy, China needs to review its approach to the Korean Peninsula, because neither economic retaliation against the South nor loosening sanctions against the North will enhance regional strategic stability and security.

The real choice facing Xi Jinping as he approaches a new U.S. administration is whether to continue to tolerate Kim Jong-un’s stubborn belligerence and defiance, which threatens the security of China and will result in greater U.S. military presence and more advanced U.S. alliance activities in the Asia-Pacific, or to employ greater pressure to stop North Korean bad behavior, working alongside South Korea, the United States, and other parties. Countries are often faced with competing interests and how leaders choose between those competing interests tells you a lot about that country. The costs of China’s coddling of North Korea now far outweigh the benefits. For China, the choice is clear.

Paul Haenle is the director of the Carnegie–Tsinghua Center based at Tsinghua University in Beijing, China. Haenle is also an adjunct professor at Tsinghua University.

Anne Sherman is a master’s in Asian Studies candidate at Georgetown University’s School of Foreign Service. She was formerly research assistant to Paul Haenle at the Carnegie-Tsinghua Center in Beijing.