China’s largest and most prominent success thus far has been in the economic sphere. Thanks to Deng Xiaoping’s policies, China, by opening itself up to the world, has allowed its economy to flourish and grow, becoming the second largest economy in the world in less than four decades. The Middle Kingdom has come to embody the notion of an Asian economic miracle, but can the miracle last?

Following Deng Xiaoping’s moves to decrease the cult of Mao Zedong and open up to the world, China moved first from a closed communist system to a planned economy, then to a “partial” market-oriented economy (where the Chinese Communist Party, CCP, is pulling the strings). China’s reforms were made gradually. The state began first by phasing out collective farming, introducing a gradual liberalization of prices and fiscal decentralization, creating a diversified banking system, and developing stock markets. Increasing autonomy was granted to state-owned enterprises (SOE), while private sector growth and foreign investments were allowed but controlled. International trade was now becoming the basis of China’s growth. These changes resulted in improved living and working conditions, far removed from China’s dire days under Mao.

However, given the unsettled nature of today’s worldwide economy, the current Chinese economic situation is under scrutiny by many foreign observers. With growth slowing, observers around the world are wondering: What is the real pulse of the Chinese economy?

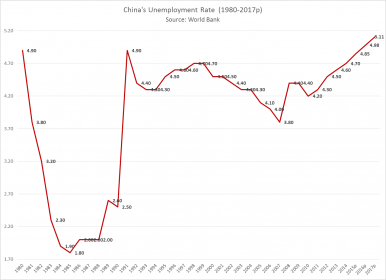

Employment

One of the factors analysts are keen to understand is the Chinese employment market. From 1980 until 2014, China’s long-term average unemployment rate was around 3.86 percent. It reached a low of 1.8 percent in 1985 and a high of 4.9 percent (both in 1980 and 1991, during global recessions). The projections for 2015-2017 are showing an unprecedented high unemployment rate.

At first, the unemployment rate seems relatively constant, but we know that China’s official statistics are just that: Official. The real numbers are probably both higher and more volatile than what it is presented.

The ‘traditional’ equation used to calculate the unemployment rate has its limitations when applied China. Both the informal economy, as well as the vestiges of communism and its social safety nets, cloud the economic landscape.

The problem for China is that while maintaining an upward trend in wealth, salaries are expected to rise as well. This is where the CCP’s headache grows. Moreover, there is the famous “harmony” pact between the CCP and the Chinese that must be kept in mind: As long as the state continues to hire millions of young people in its SOEs, as well as allowing the emergence of a middle class that is getting wealthier over time, the Chinese agree to accept limitations on their freedoms. With millions of young people joining the labor market annually, and salaries increasing, the situation is unsustainable in the long term, especially with the burden of the informal economy getting out of hand.

Moreover, the foreign companies that came to China for its cheap labor (around 20,000 companies per year since 1979) have started to leave for neighboring countries, where the lower costs are becoming more attractive each day. For example, during the period from 2010-2013, Nike production shares in China dropped from 40 percent to 30 percent while Vietnam’s shares increased from 13 percent to 42 percent. What is more worrying for China’s economy is that even some Chinese companies have started outsourcing part of their production to other countries, including Vietnam and Bangladesh, which is unprecedented.

With a labor force of around 804 million people of working age (between 15-64 years old), China cannot afford a domestic crisis because of outsourcing. That’s especially true at a time when external factors, such as the worldwide economic slowdown, oscillating stock markets, tumbling oil prices, and intense competition from other countries, including India, are complicating matters for the CCP.

That said, China continues to export its labor force overcapacity around the world, especially to Africa, through various projects. China has extended more loans to African countries than the usual Western organizations such as the World Bank; Beijing then signs infrastructure contracts that allow Chinese companies to work onsite, bringing with them the labor force and machinery. This is a rising trend in Africa, although a few African countries (e.g. Morocco) now ask for the participation of their local labor force, in order to stimulate their own economies. The infrastructure projects of the new Silk Road in Eurasia, Oceania, and Africa help as well, and China has kept on pushing them, and developing them at a good pace.

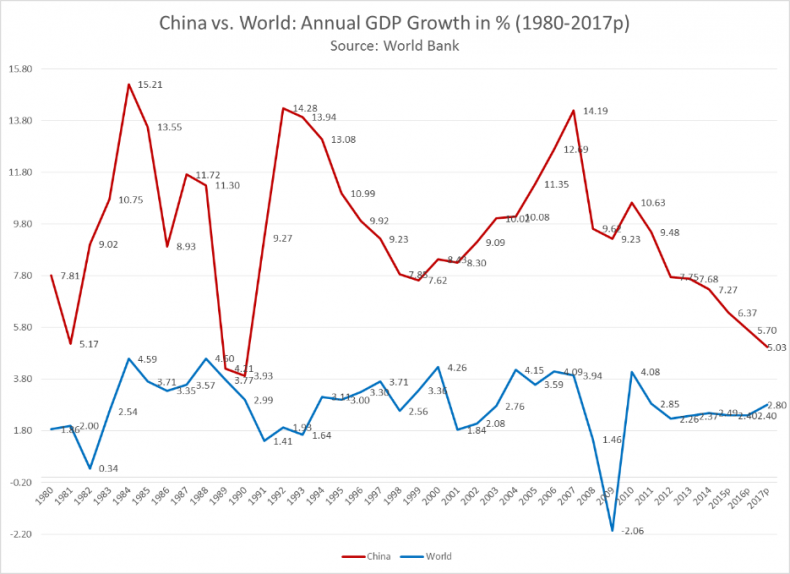

GDP Growth

China’s GDP growth trend follows a reverse trend with regards to China’s unemployment rate — as unemployment rises, GDP growth falls. In general, China has followed the same pattern as the world’s GDP growth, albeit at much higher rates. While the world’s average growth maxed out at 4.6 percent in 1983, China’s growth was then over three times higher, at 15.2 percent. China’s entry into the World Trade Organization in 2001 had a positive impact on the rise of the GDP, while the worldwide financial crisis in 2007-08 had a negative one.Projected GDP growth for 2016 and 2017 shows a decline. Despite this slowdown, China’s economy is in relatively good shape compared to many other Western countries.

However, the question of the comparison reaches its limits when China enters the equation: While Western countries are capitalist, China is not (for now). China abides by a different set of rules, and its domestic functioning is different as well: more complex, tangled, and less clear for Westerners.

This said, China’s economic slowdown is due to both external factors such as the worldwide economic slowdown (leaving China’s trading partners in bad shape) and to internal factors such as the inefficient allocation of capital by state-owned Banks, industrial overcapacity and well-known ticking debt-bomb that nobody can evaluate accurately. This year, the Institute of International Finance estimated that the total payload debt-to-GDP ratio is 295 percent. With the gloomy global economic climate, China’s debt problem is not reassuring — mostly because nobody knows the real extent of it. The uncertainty leads to speculations of all sorts, ranging from descriptions of China’s debt as “wet powder” (i.e., a situation that will be defused by the government as usual) by some optimistic investors to predictions of an unprecedented “global financial cataclysm” by other, more pessimistic hedge fund managers.

The economic slowdown has brought back talks about a potential recession, but that’s without counting on state intervention to contain it. In fact that state intervention is happening — and a closer look reveals some interesting side effects on the private vs. public sector in China. It is clear that the investments in the public sector vs. the private are unbalanced. The government invests massively in different infrastructure projects through its SOEs to keep the economy afloat and under control, creating in turn unintended consequences such as the real-estate bubble and ghost malls, buildings, and towns. Meanwhile, investments in the already-too-small private sector are shrinking.

At the same time, the state continues to adopt sector-specific regulation through a decision-making process that weighs the strength of domestic industries vis-a-vis foreign competitors, along with the perceived strategic value of the sector (for more on this, see Roselyn Hsueh’s China’s Regulatory State). On one hand, when the domestic sector is more competitive and its strategic value is high (e.g. textiles), the state applies a mixed orientation. If the strategic value is low (e.g. paper), the state applies incidental controls. On the other hand, when the foreign sector is more competitive and the strategic value is high (e.g. telecommunications), the state applies deliberate control; if the strategic value is low (e.g. automobiles), the state applies a mixed orientation.

Thus, the private sector is bound hand and foot in the face of governmental intervention. The consequences for the economy are that some industries are thriving while others are withering. Various sectors rise and fall depending on the state strategy outlined in the current Five-Year Plan (FYP). In the latest FYP, economic reforms were high on the government’s agenda. This was done in order to avoid over-dependency on heavy industries, and on exports that create an unwanted yo-yo effect in the Chinese economic landscape. But despite the talk of economic restructuring, China has yet to find a clear path to sustainable and healthier growth.

China’s Economic Future

Beijing’s aim is reaching the perfect balance to keep its side of the “harmony” pact. In order to do so, the CCP, with Xi Jinping at the helm, must pull different strings like a master puppeteer. First, the government should have a clear and well-thought-out vision about China’s economic future. They can do this by focusing on future-oriented industries — for example, investing in renewable and green energy to avoid an environmental and social catastrophe whose consequences may be devastating on a very large scale. China must avoid short-term strategies and work on long-term ones that will strengthen China’s economy over time, instead of patching it up whenever a crisis arises.

Second, China must take steps abroad as well. This would include exporting its labor force overcapacity to work on the many infrastructure projects under the umbrella of the new “One Belt, One Road” initiative sweeping through Central Asia, as well as projects won through international bidding, mainly in Africa. This would increase opportunities in the Chinese employment market. Meanwhile, attracting Foreign Direct Investment (FDI) must stay a priority, not only for coastal China, but more importantly for mainland China’s poorer western provinces. Typically, FDI come from businesses. As a bonus, this time, new groups (such as cooperatives or fair trade organizations) may enter the FDI picture to make investment sustainable and keep it in line with communism’s fundamental principle of economic equality. This will work to China’s benefit in both the economic and social spheres and will lift the economy of the poor provinces out of their current downturn.

To attract FDI, a strong currency policy must enter into force, in order to counterattack the consequences of Brexit and to counterweight the dollar, which is still playing an important role in financial markets. In addition, since the Chinese economy is strongly linked to the Western economy, decreasing its dependency on exports is certainly a must.

Third, China can keep up the “harmony” pact by satisfying needs of ordinary Chinese. These needs include improving working and living conditions in order to boost income over time. Hiring millions of young Chinese yearly in SOEs will continue to be inefficient and non-productive, according to capitalist standards, but for China this will become non-negotiable in the coming years. Stimulating the private sector to help absorb some of the labor overcapacity is another possibility, but remains a limited avenue because of state control.

One of the most important actions that could lead to a promising future for China is domestic market stimulation. With a population of over 1.3 billion people, the possibilities are endless for businesses, either Chinese or foreign. For China, capitalizing on its domestic market would require Chinese businesses to improve both their know-how and the quality of their products, as well as working on their branding through innovative strategies and education. Working with universities and professional centers to close the gap with regards to the skills shortage that companies are facing is another must. In addition to this, containing inflation will help to stimulate household consumption. Finally, continuing to fight the corruption that is undermining the Chinese society, starting with Party members as Xi has already done, and restricting the privileges of the “red” aristocracy, who are becoming insanely rich year after year, are other venues to explore.

Furthermore, the steps taken in China will also have a positive impact abroad for Chinese companies, and by extension for the Chinese economy in general. The examples of Huawei and Haier speak volumes and give early signs of what may come in the future when the Chinese wave will sweep the world.

In the meantime, China will continue to move forward, slowly aiming at harmony, the goal of all China’s rulers since the creation of the Middle Kingdom. Harmony can’t be reached directly in one go; it is reached through small alterations, Confucian-style. For foreign observers, this gives the impression that the Chinese are moving back and forth constantly, or even standing still, while actually they are gradually correcting partial imbalances in both the economic and social spheres.

All these actions aim to reach the elusive harmony that the CCP believes will secure its reputation and guarantee the stability of the country. However, the gradual pace of these various systemic corrections (economic and social) must not handicap China’s momentum, especially in the face of competition from more market-driver Asian neighbors.

Fatima-Zohra Er-Rafia is a lecturer at HEC Montreal, a consultant, and an independent researcher. She holds a Ph.D. in Business Administration with a focus on China and Japan.