SIPHANDONE, LAOS — Explorers, travelers, and traders have long been enchanted by the magical vistas and extraordinary biodiversity of the Mekong, especially here.

Swirling rapids roar through the surrounding forest to unleash the magnificent Khone Phapheng Falls in southern Laos. The surrounding myriad islands and forested islets, dotted among the tranquil waterways and braided channels of the Mekong, inspire awe and wonder. This is Siphandone (Four Thousand Islands) district of Southern Laos, nestled alongside the Cambodian border.

However, the serenity of Siphandone has recently been rudely disrupted by the dynamite-blasting of rocks, shattering the tranquil reverie of this ecotourism paradise.

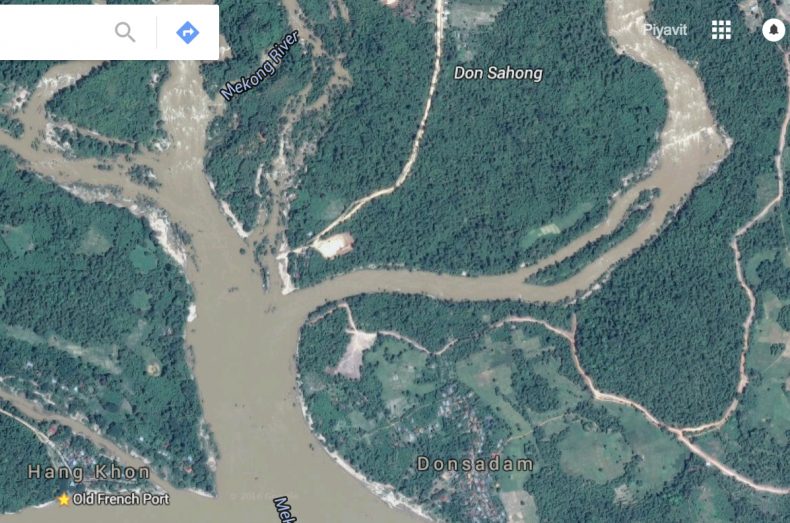

The ugly intrusion of earth-moving trucks in this picturesque landscape has accompanied the launching of the Don Sahong dam, a joint venture of Malaysian company Mega-First (MFCB) and the government of Laos, in January 2016. The dam has gone ahead without approval from the Mekong River Commission and in defiance of wide-ranging protests from regional NGOs and downstream countries Cambodia and Vietnam.

In 2012 the bitterly contested first dam on the Lower Mekong, the Xayaburi dam, a $3.8 billion project based on Thai investment and controlled by Bangkok engineering company Ch.Karnchang, began its controversial construction.

According to scientists, both dams pose a major threat to fish migration and food security.

Chhith Sam Ath the Cambodian director of the World Wide Fund for Nature (WWF), told The Diplomat, “The Don Sahong Dam is an ecological time bomb that threatens the food security of 60 million people living in Mekong basin. The dam will have disastrous impacts on the entire river ecosystem all the way to the delta in Vietnam.”

The Lao government plans to build nine dams on the mainstream Mekong, and hundreds more on other rivers and tributaries, claiming that this is the only path to development for one of the region’s poorest countries.

Just across the river from the Don Sahong dam site, on the Cambodian side of the Mekong, ecotourists gather at the Preah Romkel commune. This correspondent witnessed tourists poised with their cameras, trying to catch a glimpse of the three remaining Irrawaddy Dolphins clinging onto their fragile home despite being under daily siege from the dam-builders. This wetlands zone has been a popular destination for ecotourism in both Laos and Cambodia, but WWF warns that damming the Mekong will soon drive all the remaining dolphins to extinction.

The future site of the dam across the Sahong Channel is recognized by fishery experts as the only one out of seven braided channels of the Mekong that is deep enough and wide enough for large fish to migrate, providing effective fish passage around the rapids, rocks, and waterfalls year round. Now the dam construction has diverted all the water from the channel, and it will permanently block this natural fish migration route and passageway.

The Malaysian dam developers and the Lao Energy Ministry have airily dismissed all the protests, claiming that their fish mitigation engineering – the expansion and widening of two other channels – can fix the problem.

The Xayaburi dam also claims that its “fish-friendly turbines,” fish ladders, and locks can protect at least 28 species of fish that have been targeted for special attention by Poyry Energy the Swiss-based company hired to supervise the engineering and fish mitigation.

However the Poyry presentation and research by fish consultants Fishtek shows there are at least 139 fish species that would be blocked from swimming past the dam.

Fish mitigation on these two dams may look impressive in presentation videos, but Dr. Ian Baird, who has published many studies on Mekong fisheries, notes that “this is a high risk experiment, as these sort of mitigation measures have never been attempted before on tropical rivers.”

The Mekong Crisis: When Ecology and Economy Suffer in Tandem

The mighty Mekong, flowing for 4,630 km through the heart of Southeast Asia, is in deep crisis. The delta in Vietnam is both shrinking and sinking.

The loss of nutrient-rich sediment is wrecking havoc on the delta region. All large dams trap sediment and deprive the downstream areas of vital nutrients. Vietnam is suffering from huge sediment loss, running at 50 percent less than the regular flow. Rampant sand-mining in Cambodia and Vietnam has also aggravated the delta’s acute sediment shortage.

The miraculous but fragile ecosystem that connects the Four Thousand Islands in Laos, Tonle Sap in Cambodia, and the delta in Vietnam is directly threatened by these two dams – the Don Sahong and the Xayaburi (in addition to all the damage done by six Chinese dams upstream from Laos). Now a third dam at Pak Beng has been announced by the Lao government.

A new WWF report has drawn attention to how the dramatic decline in the health of the Mekong is not only an ecological disaster, but also a serious threat to the economy of the region. With a fresh perspective on how ecology and economy are intimately linked together, the report reminds all stakeholders, “Economic growth in the Greater Mekong region depends on the Mekong River, but unsustainable and uncoordinated development is pushing the river system to the brink.”

WWF’s lead coordinator for Water and Energy Security in the Greater Mekong, Marc Goichot, sees the delta as crucial to Vietnam’s economic future. “It produces 50 percent of the country’s staple food crops and 90 percent of its rice exports. It is one of the most productive and densely populated areas of Vietnam, home to 18 million people. Vietnam cannot lose the delta.”

But right now Vietnam is losing it. The delta is shrinking and unless there is a major policy turnaround on the Mekong, scientists in Can Tho have warned that 27 percent of its GDP, furnished by the delta, could evaporate during the next 20 years.

The strong momentum toward damming the Mekong has been greatly assisted by the widely held perception that dams are a reliable source of energy, producing great economic benefits.

The Mekong River Commission, the World Bank, and USAID have promoted dam-building with this approach, billed as “Sustainable Hydropower.”

The prevailing assumption has been that trade-offs, including negative environmental impacts, are inevitable, but we should not worry too much because improved environmental impact assessments (EIAs) and effective mitigation would provide adequate safeguards to protect ecosystems. It is only recently that researchers have been submitting these assumptions to closer scrutiny.

The credibility of this narrative is increasingly being challenged. Dr. Philip Hirsch a Mekong specialist, concluded after decades of inspecting dams that “some hydro-power impacts can simply not be mitigated – only compensated. And compensation systematically falls short.”

Most fisheries experts in the region familiar with the Sahong and Xayaburi dam projects consider that the mitigation experiment is a risky venture into uncharted waters and cannot be relied on to protect fisheries and the ecosystem.

Whereas the apparent benefits of hydropower can easily be quantified in terms of electricity, the financial losses inflicted by dams have been consistently underestimated or ignored by economists and governments.

The combined fisheries assets for the MRC countries are now valued at $17 billion and vital to the food security of tens of millions.

On the other side of the ledger, energy from 11 scheduled dams may yield economic benefits valued at $33.4 billion according to an international study on hydropower impacts on the Mekong based at Mae Fa Luang University in Chiang Rai.

But set against losses from a denuded river system and huge losses of fisheries, sediment, agricultural produce, and livelihoods, this same study predicts a loss of $66.2 billion, resulting in an overall negative impact of $21.8 billion if all 11 dam projects go ahead.

According to one of the three authors, Dr. Apisom Intralawan, “hydropower benefits have been over-stated in these figures (2015) and based on current economic data we are about to revise them.”

Hirsch confirms that “many studies show that the real costs of hydropower outweigh the benefits but the projects still go ahead.”

Can The Mekong Survive?

Wetlands ecology specialist Nguyen Huu Thien, a Vietnamese scientist based in the delta’s capital Can Tho, concluded “The sure thing we know, if the delta cannot support its population of 18 million, then people will have to migrate – migrate everywhere. The dams are sowing the seeds of social instability in the region.”

The only way forward, says the Vietnamese director of Hanoi’s Institute of Economics, Tran Ding Thien, is for Mekong countries to move beyond what he calls “the small-pond mentality.”

That seems unlikely at the moment. In Laos, Daovong Phonekeo, director general of Laos’ Department of Energy Policy and Planning, told Voice of America: “For the development of the Mekong River, we don’t need consensus!”

It is true that the 1995 Mekong Agreement does not provide for any veto on controversial dam projects, but it does enshrine principles of international river cooperation and good water governance that are undermined by the Lao government’s penchant for unilateralism.

Stuart Orr, WWF’s leader for Water Resources Practice, observes that “Water underpins our agricultural systems, our energy production, manufacturing, ecosystems, food security, and our wellbeing as humans. So if economic growth is to continue better river management is called for, that respects the limits of the ecosystem.”

Can the once mighty Mekong alter its currently blighted course of unregulated development, and this alarming rate of depletion of its natural resources?

“One step is that before we build any more dams, new green energy technologies need to be explored,” argues Hirsch. “It would be a tragedy to see the world’s greatest inland fishery destroyed for lack of imagination in applying cost-effective innovative solutions”

There also needs to be a new river-wide consensus that ultimately will have to include China.

Tran decries this small-minded approach, which clings to the “little pond of sovereignty” and cannot grasp the bigger picture of sharing water resources and respecting the whole river.

In this perspective of international scientific cooperation the Mekong should not belong to any one nation. As Tran, speaking at Mekong conference held in Can Tho in April, declared:

“If the Mekong is turned into a series of ponds and reservoirs, it is a loss not only for the region it is a loss for the world. The water that fuels the dams belongs to us all. We need to create an International Mekong Foundation and protect it.”

Tom Fawthrop is a freelance journalist and film-maker based in Southeast Asia.