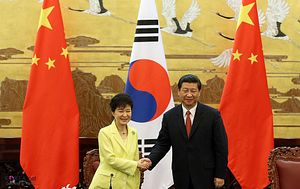

Currently, China-South Korea relations seem to be at their lowest point since President Park Geun-hye took office in early 2013. Several issues have significantly derailed the previously close relationship between Beijing and Seoul, particularly the South Korean government’s seemingly unexpected decision to deploy the U.S. Terminal High-Altitude Area Defense (THAAD) system on South Korea’s territory. Meanwhile, a scandal involving Park’s close confidante, Choi Soon-sil, has completely overturned the president’s domestic image and ruined public trust in her “capability to rule the country,” resulting in Park’s impeachment. As a result, Park’s China diplomacy has come to an end while stuck in a diplomatic dilemma, creating some uncertainty around South Korea’s future relations with China, its largest trade partner and critical stakeholder in many bilateral and regional issues.

Park’s China diplomacy has transformed through three stages: balancing, intimate relations, and the current dilemma. Her China policy was clear in the first months after her inauguration – making a mild modification to the former administration’s relatively pro-U.S. position, Park sought to once again find a strategic balance between the two great powers of China and the United States. Afterwards, ties between China and South Korea, as well as their national leaders, reached their best or the intimate stage when Park attended the September 3, 2015 military parade in Beijing. However, Seoul’s decision to deploy the THAAD system in South Korea’s territory after North Korea’s fourth nuclear test ended the short honeymoon with Beijing. This may further corner South Korea in the region, pending China’s continued reaction. Park’s China’s diplomacy all seems to have ended with this diplomatic dilemma.

Many may have regarded the final end to Park’s China dipomacy, and in particular the decision to deploy THAAD, as somewhat unexpected. However, as Robert Jervis argues in Perception and Misperception in International Politics, contradictory acts are often dependent on the perceptions (or misperceptions) of decision-makers. In view of the role of cognitive psychology in international politics, such an end to Park’s China outreach could actually be considered all too normal.

As Robert Jervis suggests, there are four common “misperceptions” held by decision-makers: seeing the behavior of others as more centralized, planned, and coordinated than it is; overestimating to extent to which one’s own country plays a central role in others’ policies; allowing wishful thinking or other desires or fears to influence perceptions; and cognitive dissonance, or committing acts that are contradictory to one’s own beliefs and ideas.

We can find evidence of the above misperceptions in Park’s China policy. For example, South Korea may have overestimated its influence over China’s peninsula policies, and may have wishfully expected China would make very significant changes to its policies (especially toward North Korea) after Park’s attendance at the military parade in 2015. Reality turned out to be contradictory to at least some of these previously held ideas and beliefs.

In a big picture, the frame of “cognitive entanglement” may help to understand the above misperceptions. By “cognitive entanglement,” I mean a psychological effect that is “entangled” with at least two competing desires. In the case of South Korea’s diplomacy with great powers, there are two obvious “entanglements”: Seoul’s desire to uphold its ties with the United States as a close ally, and to stand proudly in the mainstream world order under U.S. leadership; and the pull to join the construction of a new East Asian order, in which China plays a critically important role, or even to return to the long-gone tributary system as an inferior small neighbor. These two “cognitive entanglements” have co-existed and interacted in South Korea’s political and social lives for a quite long time,affecting the decision-making processes in South Korea’s previous administrations – Roh Moo-hyun, Lee Myung-bak, and Park Geun-hye.

No matter who will be South Korea’s president for the next five years, how to end Seoul’s “China Dilemma,” its cognitive entanglement, and maybe also the “cognitive dislocation” (from both sides), is indeed one of the most important strategic issues to be addressed. China’s decision-makers may also have to consider this issue as well.