Australian Prime Minister Malcolm Turnbull’s recently concluded visit to India could signal the beginning of a new chapter in India-Australia bilateral ties. The two countries share many commonalities, like being secular, multi-cultural liberal democracies with common colonial histories (and even a shared love for cricket).

What was the significance of Turnbull’s visit?

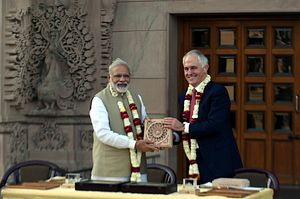

First, this visit was important because it Turnbull’s first to India as the Australian prime minister, though he and Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi had met on the sidelines of the G20 summit. His predecessor Tony Abbott had visited India in September 2014. Back then, the two countries signed an agreement for civil nuclear cooperation. Australia holds almost 40 percent of the world’s known uranium reserves and New Delhi needs uranium for its nuclear power requirements. India is looking at a massive increase in nuclear power generation as it struggles to meet the requirements of its booming economy and a growing population.

Second, there are almost 500,000 people of Indian descent in Australia who have made an immense economic contribution in the country. Moreover, Australia is the second most-popular destination for Indian students abroad, with close to 60,000 students from India pursuing their post-secondary education in Australian educational institutions last year. The Indian government is aiming to train around 400 million people in various skills by 2022 and Canberra can be a key partner in this initiative.

Third, there is growing synergy between New Delhi and Canberra on a host of issues. In the aftermath of the horrific 2004 Boxing Day tsunami, India, Australia, Japan, and the United States came together to provide relief and rescue efforts to the affected areas along the Indian Ocean rim. The four together are also part of many regional initiatives like the East Asia Summit, the G20, and the Indian Ocean Rim Association (formerly known as the Indian Ocean Rim Association for Regional Cooperation). New Delhi also requires Australian support in its bid to become a permanent member of the United Nations Security Council (UNSC) and the Nuclear Suppliers Group (NSG).

Despite all this room for cooperation, there are quite a few challenges as well. Two-way trade in goods and services between the two countries stood at $19.4 billion in 2015-16, which is far below its actual potential. Though there was some hope for an improvement, neither the anticipated CECA (Comprehensive Economic Cooperation Agreement) or the Australia-India FTA (Free Trade Agreement) were signed during this most recent visit, which is a big disappointment.

That said, the outlook for the future remains bright. Australia is a key strategic partner for India in the Indo-Pacific region and it needs no reiteration that freedom of navigation in the waters of the region is key to both countries’ continued economic prosperity. Turnbull, writing recently in an Indian newspaper, notes that “as liberal democracies, we can work together to encourage free trade and prosperity and to help safeguard security and the rule of law in our region.” Australia and India are also taking part in ongoing negotiations for the Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership (RCEP), which assumes increasing significance in the region after the United States’ pull-back from the Trans-Pacific Partnership (TPP).

Moreover, the Indian Navy, which is one of the most capable actors in the Indian Ocean region, has been collaborating with friendly navies like the Royal Australian Navy in order to tackle both traditional and non-traditional security threats in the region. India’s Andaman and Nicobar chain of islands also lie very close to Aceh province in Indonesia, another capable player in the Indo-Pacific. The Indian Navy is thus a strategic actor in the greater region.

As India looks to operationalize its ‘Act East’ policy and Australia looks to expand its ‘Look-West’ policy, there is a clear path forward for both sides to expand their partnership.

Rupakjyoti Borah is with the Institute of South Asian Studies at the National University of Singapore. He is a two-time fellow of the Australia-India Council’s Australian Studies Fellowship programme. His latest book is The Elephant and the Samurai: Why Japan Can Trust India. Views are personal.