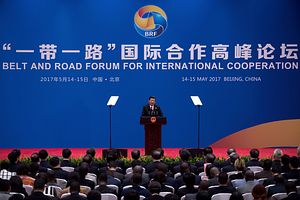

On Monday evening, the curtain closed on China’s massive Belt and Road Forum (BRF) in Beijing. The two-day summit was attended by 30 world leaders (including Chinese President Xi Jinping, who delivered both the opening and closing remarks) and official government representatives from at least 30 more countries. It served as a diplomatic showcase for China’s ambitious global project, which aims to create an interlocked trade, financial, and culture network stretching from East Asia to Europe and beyond.

The BRF served as China’s highest profile diplomatic event of the year, culminating in the 30 world leaders in attendance signing on to a joint communique that championed globalization and free trade.”We reaffirm our shared commitment to build open economy, ensure free and inclusive trade, oppose all forms of protectionism including in the framework of the Belt and Road Initiative,” the communique read in part.

Even if the larger focus of the event was on the global implications of the Belt and Road, that topic is best understood through the discrete bilateral arrangements China has with various interested parties. According to Xi, during the course of the forum a total of 68 countries and international organizations signed agreements on furthering the Belt and Road concept. That includes the official inking of a free trade agreement with Georgia; energy deals with Saudi Arabia, Azerbaijan, and Russia; and a strategic cooperation deal with Interpol, among other bilateral arrangements.

In his keynote address at the BRF’s opening ceremony, Xi likewise highlighted the achievements of the initiative so far in a series of bilateral examples. In the three-plus years since rolling out the concept, China has successfully “deepened policy connectivity” with a number of other states and groupings, Xi said. That includes aligning the Belt and Road with the development strategies of the Russia-led Eurasian Economic Union, ASEAN, Kazakhstan, Turkey, Mongolia, Vietnam, the United Kingdom, and Poland. Xi also highlighted a few of the more high-profile projects under the Belt and Road framework:

“We have accelerated the building of Jakarta-Bandung high-speed railway, China-Laos railway, Addis Ababa-Djibouti railway, and Hungary-Serbia railway, and upgraded Gwadar and Piraeus ports in cooperation with relevant countries.”

Notably, the first two projects on that list have run into a number of issues in implementation, as The Diplomat has discussed in detail before.

According to Xi, “Total trade between China and other Belt and Road countries in 2014-2016 has exceeded $3 trillion, and China’s investment in these countries has surpassed $50 billion.” Those figures were boosted by the creation of financing mechanisms specifically to carry out the Belt and Road vision, including the multilateral Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank (AIIB) and China’s Silk Road Fund.

Indeed, one of the major announcements from the BRF was Xi’s pledge to further boost funding for the project. In his keynote, Xi promised China will funnel an additional RMB 100 billion ($14.5 billion) into the Silk Road Fund, while the China Development Bank and Export-Import Bank will set up new lending schemes of 250 billion ($36.2 billion) and RMB 130 billion ($18.8 billion), respectively, for Belt and Road projects. In addition, China will provide RMB 60 billion ($8.7 billion) for humanitarian efforts focused on food, housing, health care, and poverty alleviation.

All that lending has long-term costs, both for China and for the loan recipients. Poorer countries often struggle to repay billions of dollars in loans, even at low-interest rates, while Chinese banks take the hit when bad debts can’t be collected. On the sidelines of the BRF, Reuters explored concern from China’s policy banks about granting too many loans to countries that are seen as a bad risk (with Venezuela, which owes China $65 billion, as the poster child).

Xi also outlined China’s areas of emphasis for the Belt and Road. Key areas of focus include industrial development, financial integration and reform, and infrastructure construction. In addition to those three stalwarts, which have defined every high-profile Belt and Road project to date, Xi stressed the need for “innovation-driven development” calling for “cooperation in frontier areas such as digital economy, artificial intelligence, nanotechnology and quantum computing, … the development of big data, cloud computing, and smart cities.”

Aside from the economic underpinnings of the Belt and Road, Xi took the opportunity to reiterate China’s vision for regional and global peace and security, which he stressed was a prerequisite for bringing the Belt and Road to fruition. Xi called for mutual respect and non-interference, as well as settling differences through political dialogue. Xi also included China’s old refrain that alliances are outdated in the modern world, calling instead for countries to “forge partnerships of dialogue with no confrontation and of friendship rather than alliance.”

Such pronouncements have only in the past only exacerbated concerns that the Belt and Road is an economic veneer for China’s grander geopolitical ambitions – namely, placing itself as the central hub of the Eurasian continent. Geopolitical worries kept India from sending any official representative to the summit; the United States, which has also expressed doubts in the past, only announced at the last minute that it would send a government delegation. Xi’s keynote speech also included China’s latest attempt to assuage those concerns:

“We are ready to share practices of development with other countries, but we have no intention to interfere in other countries’ internal affairs, export our own social system and model of development, or impose our own will on others. In pursuing the Belt and Road Initiative, we will not resort to outdated geopolitical maneuvering. What we hope to achieve is a new model of win-win cooperation.”

He added that “all countries, from either Asia, Europe, Africa or the Americas, can be international cooperation partners of the Belt and Road Initiative.” That may not be entirely comforting, however — China’s inclusivity saw North Korea attend the BRF even as Pyongyang launched its latest missile test to international criticism.

Overall, the Belt and Road Forum was unlikely sway anyone’s perceptions of the massive project. None of the announcements or speeches made at the forum fundamentally altered preexisting interpretations of the Belt and Road (both good and bad). Anyone familiar with relevant policy documents from the Chinese government (most notably the “Visions and Actions on Jointly Building Silk Road Economic Belt and 21st Century Maritime Silk Road” issued in 2015) was not going to glean much new information from the BRF. It was more a celebration of the project – and China’s diplomatic clout in getting it accepted by as many countries as possible – than an expansion of its parameters or a serious consideration of the challenges that face the Belt and Road. In other words, the BRF was all about optics – the sheer number of attendees and agreements signed – rather than substance.

China was clearly pleased with those results; Xi announced on Monday that a second Belt and Road Forum will be hosted in 2019.