On May 15, the government of Philippine President Rodrigo Duterte signed a letter of intent to purchase defense assets from one of China’s top state-owned defense firms. The move is just the latest sign that Manila is flirting with the idea of a stronger defense relationship with Beijing, despite the well-known challenges in doing so.

Since coming to office in June, Duterte has sought to diversify his country’s foreign policy away from its traditional ally the United States and toward other major powers with whom the Philippines has not had close ties with previously, most notably China (though Russia is another interesting case).

As I have noted before, Duterte is hardly the first Philippine leader to attempt such a rebalance or recognize the economic imperative of closer ties with China (See: “The Limits of Duterte’s US-China Rebalance”). Nonetheless, even some of the ongoing initiatives we have seen so far in the defense realm, from closer coast guard cooperation to offers on military equipment, are admittedly things that would have been unthinkable even just a year ago, given the poor state of ties after years of saber-ratting in the South China Sea (See: “What’s Behind the New China-Philippines Coast Guard Exercise?”).

On defense equipment itself, however, little progress appeared to have been made up to this point. Back in December, Philippine Defense Secretary Delfin Lorenzana disclosed that China’s ambassador to the Philippines, Zhao Jianhua, had offered to provide $14.4 million worth of equipment to Manila for free in what would be considered military assistance, along with a more ambitious but strangely less discussed $500 million long-term soft loan for other equipment (See: “What’s the Deal With China-Philippines Military Ties?”). While Lorenzana had indicated then that things could move quite quickly – with a deal finalized by the end of 2016 and equipment received by the second quarter of 2017 – there had been little public disclosure of advancements since that point.

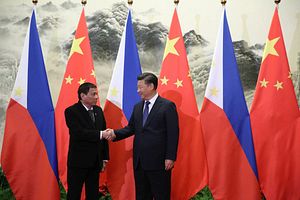

This past week seemed to suggest some progress in translating that initial commitment to reality. During Duterte’s trip to China for the Belt and Road Forum over the weekend, he and the Philippine delegation received a courtesy call from Poly Technologies, one of China’s top state-owned defense manufacturing and exporting firms. Lorenzana later told reporters that the Chinese firm had offered “a wide array of defense equipment.” On Monday, Lorenzana and Poly Group President Zhang Zhengao signed the letter of intent (LOI) in Beijing.

The news led to a series of headlines across Philippine newspapers about a new deal and its implications for Manila’s alignments with the major powers. Though this does represent some progress, the lack of details we have about the LOI itself and the challenges and uncertainties inherent in the Sino-Philippine relationship more broadly suggest that caution is warranted before jumping to conclusions.

For one, the significance of the deal itself still remains unclear. Lorenzana stressed that the letter of intent was not binding, which they indeed are not. Letters of intent in such contexts often have little worth beyond either conveying some sort of preliminary desire by both parties to enter into an actual agreement or outlining the general bounds of a potential arrangement at a later date. Lorenzana emphasized this was just the first of a series of steps that would be required for any transactions to take place, and he repeated what he said last year about the need for a technical working group that would first have to look at the company’s products. He also clarified that though the Philippines did have a general sense of what it required – including airplanes, drones, and fast boats – this would have to be finalized with the consultation of the various services.

“We are not saying that we will buy from them or we will not buy from them, but if we need anything from the Chinese defense industry, then we’re going to procure using the loan they are going to offer to us,” Lorenzana said in a rather non-committal response.

Furthermore, even assuming that these steps do proceed as planned, the exact path for future collaboration is still a rather muddy one. Take the issue of financing, for instance. Though Lorenzana mentioned at the press conference that the Philippines could use Chinese loans to procure weapons, he also said that Manila would only use the funds if it did not have sufficient money from the existing budget for its military modernization (See: “What’s Next for Philippine Military Modernization Under Duterte?”).

These are not just mere technicalities. As a number of countries have already found out, the original financial terms they have reached with Chinese entities have at times caused initial controversy or eventual challenges or both. Such specifics would need to be sorted out before a deal is made.

And that’s not even getting to the challenges that remain to strengthening Sino-Philippine ties in this dimension, which Duterte is not immune to. One is how the optics of Manila buying weapons from a country with which it is having disputes in the South China Sea will play into domestic public opinion, a point that continues to be made in some articles in local media outlets. Though Philippine officials are technically right that disputes in one area do not necessarily have to undermine defense collaboration in another, they too are aware that Philippine public opinion continues to be wary of China and supportive of the United States as well as some other traditional partners (See: “The Truth About Duterte’s ‘Popularity’ in the Philippines”).

Even assuming that this is something that the Duterte administration can get past, there are other concerns that will need to be addressed if Manila is to do business with a new partner in this area as opposed to traditional ones like the United States. These range from national security sensitivities to interoperability, an issue some in the Philippine defense establishment have already raised, noting that alternatives with other traditional partners do exist (interoperability is also an issue in the case of Russia, as I have noted before) (See: “A New Russia-Philippines Military Pact?”).

And then there’s the reality that it is still early days, and that Duterte’s initial China approach could well freeze or at least cool further down the line and affect cooperation in the defense realm. As I have recalled before, the two Philippine presidents that preceded Duterte, Gloria Macapagal Arroyo and Benigno Aquino III, learned the limits of engaging Beijing the hard way: Arroyo when she was accused of selling out Philippine interests to China, and Aquino as China began dialing up the temperature on the South China Sea even early on in his term. Duterte could similarly see his olive branch to Beijing wither and have to turn to other established partners like Australia, Japan, and the United States for the Philippines’ defense needs. Indeed, as it is, his China outreach has already run into some familiar challenges, including in the South China Sea (See: “The Truth About Duterte’s ASEAN South China Sea Blow”).

And given that we are still not even through the first year of Duterte’s single six-year term, with the trajectory of the U.S.-Philippine alliance as well as broader Philippine foreign policy still left uncertain, it would also be premature to conclude that his initial views will end up being his eventual legacy, and that initial exploration of cooperation will actually generate tangible results (See: “Recalibrating US-Philippine Alliance Under Duterte”). Things could well change further down the line in Manila’s ties with the major powers, as they have done in the past. One thing to watch in this regard, as I have suggested earlier, is U.S. President Donald Trump’s likely summit meeting with Duterte (See: “Why Trump Must Go To ASEAN and APEC in the Philippines and Vietnam”).

This is not to pour cold water over what we are have seen in Sino-Philippine defense relations so far, which, as I noted earlier, constitutes significant progress from the almost non-existent state under Aquino. But it is so suggest that we ought to be careful about reading too much into things too early on and with so few details, no matter how tempting it may be to do so.