On April 12, China’s Ministry of Education announced that the Xinjiang Uyghur Autonomous Region (XUAR), the restive Muslim province in China’s far west, would no longer provide added points to university entrance exam applicants from bilingual educational tracks. Bilingual education was established in 2004 with the aim to promote Chinese language education among the region’s ethnic minorities, especially the Uyghurs. In the bilingual system, the role of the minority language is typically restricted to that of a single language subject, creating a highly immersive Chinese language environment.

Since educational levels of China’s minorities have often been far inferior to that of the Han majority, the state instituted a series of preferential policies in order to equalize access to higher education and public employment. To this end, ethnic minorities receive extra points on the university entrance exam (gaokao) as well as public recruitment exams, provided they take them in Chinese instead of their own native language. Minorities in Xinjiang’s bilingual education take the gaokao in Chinese, and hence qualify for the added points.

From the late 2000s, several influential Chinese intellectuals and academics, such as Ma Rong and Hu Angang, began to advocate what came to be called a “second generation of ethnic policies” (SGEP). The SGEP camp argues that preferential policies based on ethnicity not only endanger social cohesion by strengthening distinct ethnic identities, but can also give unfair advantages to minority students from better educational backgrounds. Moreover, preferential treatment is considered to dampen the minority’s motivation to “work hard.” Instead, preferential treatment should solely be based on socio-economic need. In disadvantaged regions, all residents regardless of ethnicity should receive such support. Despite his sympathy for an integrationist approach to the minorities, China’s president Xi Jinping has been hesitant about adopting such measures, presumably since substantial impingements on ethnic benefits could further destabilize restive minority regions.

With the abolishing of added points for minority applicants from bilingual education, Xinjiang has in fact already taken a second step toward SGEP demands. In 2015, the province established a region-based preferential system for the southern four prefectures, home to most of Xinjiang’s Uyghur population and economically far behind the rest of the province. In these prefectures, residents of any ethnicity can receive 10 added points if they take the gaokao in Chinese. However, this policy did not entirely remove ethnicity-based preferentiality. Applicants with at least one ethnic minority parent receive 50 points. In Xinjiang’s other prefectures, only those with two parents from minority backgrounds qualify for 50 added points, while those with one minority parent only obtain 10 points.

Chinese-Educated Minorities Are Becoming Increasingly Competitive

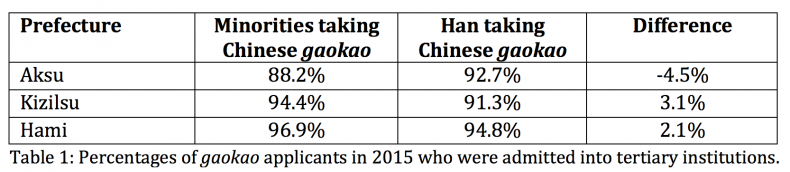

While Xinjiang’s new policies are rendering the preferential admissions system ever more complicated, evidence from higher education and government recruitment supports them. Table 1 shows tertiary acceptance shares by exam language. For the Chinese language gaokao, admission shares of minorities and Han are actually very similar.

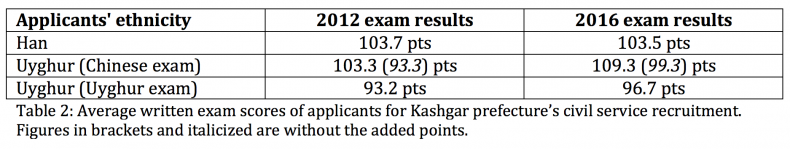

Additional evidence for the increasingly strong performance of Chinese-language educated minorities comes from Kashgar’s civil service recruitment. Here, minority applicants who took the exam in Chinese received 10 added points to their score. Alternatively, minorities could sit the exam in Uyghur, in which case they did not quality for such preferential treatment.

In 2012, Uyghur applicants who took the exam in either Chinese or Uyghur achieved about the same points average, each group scoring about 10 points lower than Han applicants. However, due to the added 10 points, Uyghurs opting for the Chinese exam reached nearly the same average as the Han.

By 2016, Chinese exam-taking Uyghurs had became the highest-performing applicant group, improving their average score by 6 points and surpassing Han applicants’ average scores due to the added points. While the Kashgar case is not representative for all of Xinjiang, it reflects the growing competitive advantage of Chinese-educated minorities over both Han and other minorities.

Chinese-Educated Minorities Are Displacing Those From Minority-Language Education

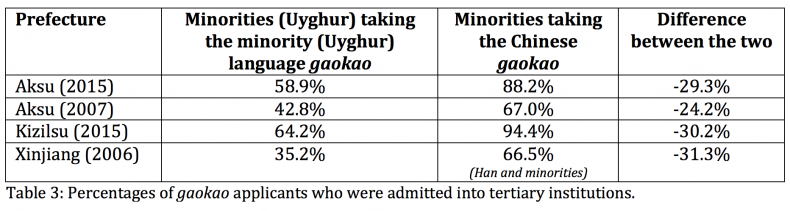

Aided by the added points policy, Chinese-educated minorities are increasingly displacing their peers from minority language education. Table 3 shows that tertiary admission shares for these two groups differ considerably, on average by about 30 percent. Notably, this gap has not been improving for the regions shown below.

This troubling fact may be related to a trend that has gone largely unnoticed. Minorities who take the gaokao in their native language do not receive added points. Instead, they benefit from a lower minimum points level for tertiary admission. The gap between this level and the higher points level required for Han applicants has gradually narrowed, from 163 points in 1987 to 89 points in 2006 to only 66 points in 2016. While minorities in bilingual education are about to lose a 50-point advantage, those in minority language education have been slowly losing nearly a 100-point advantage over the past three decades.

In 2015, Xinjiang’s government proudly cited a 78 percent gaokao admission share for its impoverished southern regions, just barely below the whole province’s 81.4 percent level. This outcome was celebrated as the direct result of the new preferential policy for the disadvantaged south. However, the admission rates shown in table 3 for Aksu and Kizilsu, two of the four southern prefectures, paint a different picture. They indicate that the south’s surprisingly high admission share is largely the result of Chinese-educated minorities as well as the Han, whose 2015 admission shares in Aksu and Kizilsu stood at a staggering 93 and 91 percent. In contrast, the percentage of Uyghur language gaokao takers in Aksu who were admitted into a tertiary institution fell from 47 percent in 2000 to 22 percent in 2015. Consequently, the new policy is powerfully promoting Chinese-medium applicants, while minority language applicants are losing out.

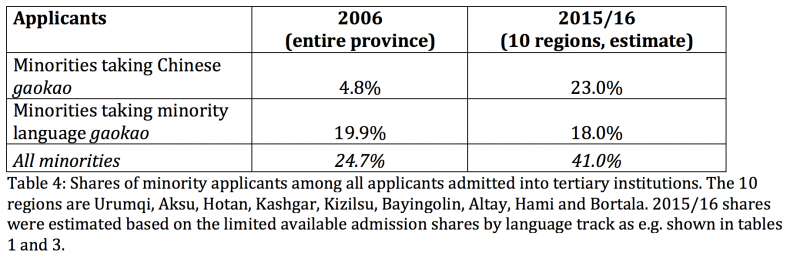

The displacement of minority language applicants for tertiary study is also evident from overall gaokao acceptance shares (table 4). Whereas in 2006, minority applicants who passed the gaokao in Chinese made up a fifth of all accepted minority applicants (4.8 of 24.7 percent), an estimate for 2015/16 indicates that they likely constituted over half of them (23 of 41 percent). While overall minority representation increased from 24.7 to 41.0 percent, the share of those admitted based on the minority language exam fell from 19.9 to an estimated 18 percent.

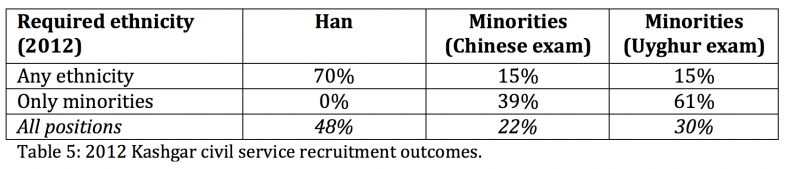

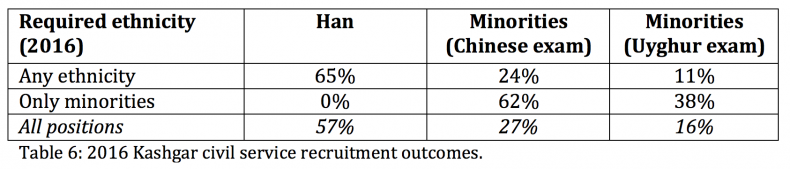

Similar displacement dynamics are reflected in the Kashgar civil service recruitment outcomes. There, each position comes with an ethnicity requirement. Some are open to any ethnicity, while others are restricted to minorities. Applicants can take the exam in either Chinese or Uyghur.

Tables 5 and 6 below indicate that in 2012, minorities who took the exam in Uyghur secured most positions restricted to minority applicants (61 percent). By 2016, the situation was the reverse, with 62 percent of such positions being awarded to minorities who took the Chinese recruitment exam. Between 2012 and 2016, the share of jobs secured by minorities who had taken the exam in Uyghur nearly halved, falling from 30 to 16 percent in a prefecture whose population is 92 percent Uyghur.

Conclusion: Added Points Are a Mixed Blessing for Disadvantaged Minorities

Overall, the removal of the added points advantage for minorities in bilingual education showcases the government’s success in fostering a generation of minorities who can compete against the Han majority in the Chinese language. However, minorities whose education centers on their own ethnic language are rapidly falling behind. Increasingly, competitive dynamics in Xinjiang and elsewhere are based on educational language rather than ethnicity. This means that intra- rather than inter-ethnic competition is becoming the most pertinent challenge to social stability in restive minority regions.

From the perspective of Xinjiang’s ethnic minorities such as the Uyghurs, added points policies are therefore a mixed blessing. On the one hand, they increase overall minority recruitment shares in higher education and public employment. On the other hand, they speed up the process of Chinese-educated minorities displacing their native language-educated peers, and therefore promote cultural and linguistic assimilation. Therefore, the planned abolishing of the added points policy is not all bad news for minorities.

Adrian Zenz obtained his Ph.D. in social anthropology at the University of Cambridge, and is currently lecturer in social research methods at the European School of Culture and Theology, Korntal, Germany. His research focus is on China’s ethnic policy and public recruitment in Tibet and Xinjiang (the latter in collaboration with James Leibold). Adrian is author of Tibetanness under Threat (Global Oriental, 2014) and co-editor of the “Mapping Amdo” series of the Amdo Tibetan Research Network.