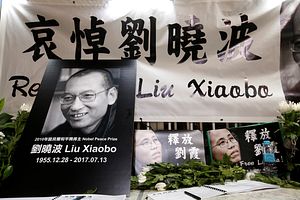

As Chinese Nobel Peace Laureate Liu Xiaobo lay on his deathbed in a hospital late June, a mysterious video surfaced on YouTube, showing him undergoing medical treatment while in custody and telling medical staff he “greatly appreciated” the care he was given.

While news of his terminal liver cancer was met with shock and disbelief around the globe, China’s state propaganda machine swiftly moved into high gear to make sure its version of the story was dominating public discourse.

When Liu died two and a half weeks later, another video appeared on a Shenyang provincial government website, with a narrator saying Liu had been treated by top medical experts and foreign doctors in a “humanitarian spirit.” Just hours after his passing, doctors explained to a press conference that Liu couldn’t have traveled abroad to seek treatment as he wished due to the severity of his illness.

At another press conference, a two-minute video clip of the government-controlled, sparsely-attended funeral and the scattering of ashes into the sea was shown to journalists from mainly overseas media outlets. Amid accusations that the family was pressured into accepting the authorities’ arrangement to ensure there will be no gravestone, Liu’s elder brother extolled the benefits of “sea burial” at the briefing and thanked the party and the government profusely for the “humanitarian care” shown to his family.

These events are just the latest example of how the Chinese authorities have become increasingly savvy in their use of modern media tools to shape their own versions of events — while behind the scenes, the suppression continues to intensify.

The government’s attempt to monopolize the storyline related to Liu’s illness and death is part of a radical change in the way the Chinese government uses the media. Instead of hushing up issues it found embarrassing like in the past, it is now aggressively manipulating the public discourse.

Although Chinese media has always been controlled by the Communist Party, there had been periods of relative liberalization after the Cultural Revolution in the early 1980s and again in the late 1990s and 2000s, when the press was allowed a degree of freedom to run investigative stories that helped uncover corruption and limit the power of local governments. But under Xi Jinping, the media has become a tool which exists to shore up the authority of the Communist Party, and not to challenge it.

The leadership’s intolerance for a free media cannot be more apparent. In 2013, an internal party edict known as Document No. 9 condemned seven subversive influences on society, one of which was “Western notions of press [freedom],” among other concepts such as “Western constitutional democracy” and “universal values” such as human rights and free speech.

Xi’s ambitious push to further the Chinese government’s dominance in public discourse was revealed on February 19, 2016. He made a high-profile tour to three key state media outlets in Beijing — the People’s Daily, Xinhua News Agency and China Central Television — ordering staff to dedicate their loyalty to the party.

“We must tell a good story of China,” Xi told visibly excited staff members, including foreigners, during a prime-time newscast.

In a speech to a party conference on the same day, Xi emphasized that the news media must uphold the “party’s leadership” and insist on “the correct guidance of public opinion” and “positive propaganda.”

The state media “bears the party surname,” Xi was quoted by People’s Daily as saying.

“Everything in the party’s news and public opinion work must materialize the will of the party, reflect the party’s opinion, safeguard the central party leadership’s authority and unity,” he said.

The state media used to maintain a stony silence over the suppression of activists, social unrest, and other news deemed sensitive. But in recent years, selected party news outlets or government organs are deftly using state-controlled and social media tools to take the lead in shaping the Chinese government’s own versions of these events.

“Troublemakers” such as activists and rights lawyers are now portrayed as agents of “foreign hostile forces” intent on destabilizing the regime. After the government rounded up over 300 human rights lawyers and activists in a crackdown that started July 2015, the Communist party mouthpiece People’s Daily accused the lawyers at the core of the crackdown of being part of a “major criminal gang” that “seriously disturbed social order.”

When four of them went on trial in August last year, a video on the microblog of the Communist Youth League featured images of rights lawyers and activists at scenes of protests, accusing them of subverting state power under the pretext of “democracy, freedom and rule of law.” The video warned against the danger of a “color revolution,” vowing that China would never become “the next Soviet Union.”

If simply smearing the reputation of these “enemies of the state” is not enough, then there are “self-confessions” on state television.

When dissident journalist Gao Yu was detained by the authorities for allegedly “leaking state secrets abroad” in 2014, she was shown on state television admitting to her supposed guilt. She later retracted her confession, saying it was made under duress. Peter Dahlin, a Swedish NGO worker detained for his human rights work, was paraded on state television in early 2016, claiming he had “violated Chinese law… and hurt the feelings of the Chinese people” — after he regained freedom he said he had been forced into making an appearance.

The party also uses social media to promote its campaigns. As part of a national security drive earlier this year, cartoons and video clips were posted on the microblog accounts of China Central Television, the Communist Party Youth League, and the Ministry of Public Security showing how ordinary people could identify spies and report suspicious people to the authorities. “Come on, be brave, go and report!” said a narrator to the beat of rap music on one video.

In the case of Liu, most state media outlets stayed mute with the exception of the Global Times and the English version of People’s Daily. These papers, which are the Chinese government’s voice to the outside world, lashed out at Western countries over their criticism of Liu’s treatment in strident commentaries.

Global Times’ English edition said Liu was “a victim led astray by the West” while the People’s Daily insisted that Liu had “long engaged in illegal activities aimed at overthrowing the current government.” The Chinese edition of Global Times accused “Western hostile forces” of meddling in China’s internal affairs and argued that China has already shown mercy to Liu, whom it called “a criminal,” without mentioning that he was a Nobel Peace prize laureate.

To hide the harsh reality in circumstances related to Liu, the Chinese authorities’ attempts to control public discourse, or the “guidance of public opinion,” continues to be seen even after his death.

Liu’s name remains blocked on internet search engines and social media sites in China — even candle-shaped emoji have been banned.

A Shenyang city government spokesman told reporters after Liu’s funeral that his widow was “free,” but two weeks after his death, she is still nowhere to be found. Liu Xia has been under house arrest since her husband was awarded the Nobel Peace Prize in 2010. Apart from appearing in images released by the authorities, she has not been seen in public and her friends are unable to reach her, even by phone.

Supporters of Liu Xiaobo who gathered by the seaside in several cities to commemorate him were taken away by the police. Others who gathered to commemorate him privately were questioned by the police.

The suppression continues.

Verna Yu is a freelance journalist based in Hong Kong. She has covered China for over a decade and has been the recipient of seven Human Rights Press Awards and three SOPA awards. She worked for the South China Morning Post, AP, and AFP and her stories have been published in the Diplomat, the New York Times, Ming Pao, and Hong Kong Economic Journal.