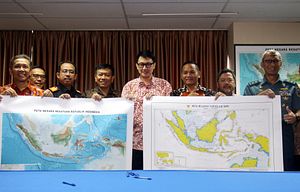

On Friday, Indonesia announced that it had renamed a resource-rich northern portion around its Natuna Islands, which lie in the southern end of the South China Sea, as the North Natuna Sea. The move, which was part of the unveiling of an updated national map that was months in the making, reflects the Southeast Asian state’s determination to safeguard its claims even amid the lingering challenges inherent in doing so.

Although Indonesia is not a claimant to the South China Sea disputes strictly speaking, it has nonetheless been an interested party, especially since China’s nine-dash line overlaps with Indonesia’s exclusive economic zone (EEZ) around the resource-rich Natuna Islands.

As I’ve argued elsewhere, Jakarta’s traditional South China Sea position since the 1990s might be best summed up as a “delicate equilibrium” – seeking to both engage China diplomatically on the issue and enmeshing Beijing and other actors within regional institutions (a softer edge of its approach, if you will) while at the same time pursuing a range of security, legal, and economic measures designed to protect its own interests (a harder edge) (See: “Indonesia’s South China Sea Policy: A Delicate Equilibrium”).

Though we have seen somewhat of recalibration within this delicate equilibrium as well as newer developments since Indonesian President Joko “Jokowi” Widodo came to office – from more run-ins with Chinese vessels to some upgrading of facilities in the Natunas and even visits by Jokowi to the area – the overall approach itself has not fundamentally changed (See: “Will Indonesia’s South China Sea Policy Change Amid China’s Assertiveness?”).

The latest development fits into this broader pattern. With this move, Jakarta is signaling that it is willing to take new steps to even more clearly underline its long-held position that it does not recognize China’s notorious nine-dash line claim.

Indonesia’s North Natuna Sea is just the latest in a succession of such designations we have witnessed among Southeast Asian States. The Philippines refers to the South China Sea as the West Philippine Sea, and Vietnam refers to it as the East Sea.

As with these other cases, from an Indonesian perspective, that clarity has more than just symbolic significance. As Jakarta begins to register the new name with the International Hydrographic Organization (IHO), such moves will take on broader significance and will be critical in ensuring that its actions are aligned with international law. In that vein, it is no coincidence that the Indonesian government directly mentioned the the arbitral tribunal ruling on the Philippines’ South China Sea case against China as part of its rationale for the name change. Jakarta is trying to ground the domestic change partly in terms of its adherence to international law.

Beyond this, being clear with respect to the extent of the Southeast Asian state’s boundaries also has bearing on more practical grounds in terms of the oil and gas resources that lie beneath the continental shelf as well as the legality of other moves that it can take to reinforce its claims, including patrolling waters.

As significant as this legal move might be, its effectiveness remains to be seen. As I had warned last year, and as the tribunal award has demonstrated, such legal decisions alone are unlikely to stop China’s assertiveness unless they are paired with actions in other areas as well, including in the military and even the economic realm (See: “What the South China Sea Ruling Means”).

And therein lies Indonesia’s problem. Though Indonesia may be on firm ground legally speaking, its military capabilities still remain quite limited (See: “Confronting Indonesia’s Maritime Coordination Challenge“). Furthermore, the Jokowi government – not unlike other Southeast Asian countries – has found it difficult to strike the proper balance between cooperating with China where interests converge and effectively confronting it where differences remain.

In addition, though the Natunas were no doubt a major factor in Indonesia’s unveiling of its new map, we also ought to keep in mind that there are other developments too in Jakarta’s diplomacy that are affecting how it thinks about its borders. In the complete rationale for the new map, Indonesia’s Deputy Coordinating Minister for Maritime Affairs Arif Havas Oegroseno noted not only the Natunas as a factor, but also other developments like Jakarta’s delimitation agreements with Singapore and the Philippines.

The inclusion of a list of reasons for the new map, rather than just the Natunas alone, no doubt has its own diplomatic utility. But at the same time, though this often does not get as much attention among outside observers, the Jokowi government had made progress on outstanding border issues with neighboring states a key priority from the outset, which was tied to the broader emphasis on preserving sovereignty and territorial integrity (most visibly manifested by the blowing up of illegal fishing vessels) (See: “Explaining Indonesia’s Sink the Vessels Policy Under Jokowi“).

That broader perspective should be kept in mind as these developments unfold, rather than an exclusive focus on China and the South China Sea. As Indonesian diplomats often note, including Oegroseno himself in these pages, they carry a significance of their own.