After North Korea successfully launched its second intercontinental ballistic missile on July 28, 2017, U.S. President Donald Trump criticized China again: “I am very disappointed in China. Our foolish past leaders have allowed them to make hundreds of billions of dollars a year in trade, yet… they do NOTHING for us with North Korea, just talk.”

Trump appears to assume that China is able, but not willing, to curb North Korea’s nuclear ambition. Is that assumption right? Does China really have enough influence to rein in North Korea? In fact, Beijing’s leverage over Pyongyang is a lot more limited than he believes.

True, China shares a border with North Korea and is the country’s sole ally. Having communist ideology in common, it also fought for North Korea during the Korean War. Today, China accounts for more than 80 percent of North Korea’s total foreign trade volume. Nevertheless, none of these – sharing the same border and ideology, a military alliance, or massive economic trade – necessarily guarantees Beijing can curb Pyongyang’s nuclear ambitions. Here an interesting analogy from Cold War history is worth considering.

The United States was extremely anxious about China’s attempt to build nuclear weapons in the early 1960s. Just like today’s Pyongyang, Beijing at that time was entrenched in a mindset that it was threatened by “American Imperialism,” because it didn’t have nuclear weapons. “The reason why [American] Imperialism is looking down on us is that we do not have atomic bombs,” said Mao Zedong.

The prospect of Chinese nuclear capabilities struck fear in the hearts of U.S. policymakers. President John F. Kennedy told the Director of Central Intelligence that “[Nuclear China] would so upset the world political scene [that] it would be intolerable.” Back then, just like now, the United States even considered taking military action to halt China’s nuclear program. Fortunately, a direct military confrontation between the two was avoided thanks to the Joint Chiefs of Staff considering it “unrealistic to use military force.”

What the United States decided to do instead was approach the other superpower at that time: the Soviet Union. The United States wanted the Soviet Union to exercise its influence to thwart Beijing’s nuclear desire or acquiesce to military action by Washington. Kennedy sent a secret cable to Assistant Secretary of State, Benjamin H. Read, who was in charge of communication with Moscow, stating, “You should try to elicit Khrushchev’s view of means of limiting and preventing Chinese nuclear development and his willingness either to take Soviet action or to accept U.S. action armed in this direction.”

Moscow’s response, however, was not positive. In fact, neither scenario was a feasible option to the Soviet Union. Potential Chinese instability following a counterforce strike was definitely not in the Soviet’s interest. Moreover, Moscow didn’t have much leverage over Beijing.

Yes, they were both communist countries and had a military alliance, shared a border, and engaged in massive economic trade. However, that didn’t mean the Soviet Union had enough influence on China. In effect, the once-brotherly relations between the two countries had already deteriorated by the 1960s to the point where each openly criticized the other. Ideologically, they were no longer in the “same” communist bloc; while Mao was adhering to orthodox Marxism and Leninism, Khrushchev conceived of a “peaceful coexistence” with capitalist countries. In 1961, Beijing denounced Soviet leaders as “revisionist traitors.”

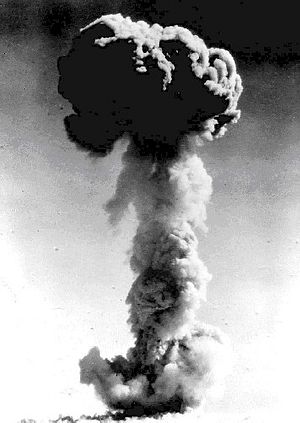

As a result, by the time the United States approached the Soviet Union, Moscow’s leverage over Beijing had already drastically decreased. Moscow had stopped providing nuclear technology to Beijing at least three years prior, withdrawn some 1,400 Soviet advisors, and cancelled more than 200 scientific projects with China. Consequently, the United States and the Soviet Union were not able to halt China’s nuclear development and helplessly witnessed China’s first successful detonation of nuclear weapons on October 16, 1964. President Lyndon B. Johnson called it, ”the blackest and most tragic day for the free world.”

This situation is analogous to Sino-DPRK relations today. China and North Korea no longer boast about their fraternal relations, especially after Kim Jong-un took office. Kim Jong-il, the former leader of the reclusive regime, allegedly left instructions to his son two months before his death, warning that, “Historically, China is the country that forced difficulties on our country… Keep this in mind and be careful. Avoid being exploited by China.” Following this instruction, Kim Jong-un tried to keep his distance from China. One example is the purge of his uncle, Jang Song-thaek, and Jang’s pro-China faction in 2013. The recent assassination of Kim Jong-nam, who had been living in Macau under Chinese protection, is also widely interpreted as Kim Jong-un’s effort to reduce China’s influence over North Korea. It is also noteworthy that Kim Jong-un has never paid a visit to China.

Just like Sino-Soviet relations in the 1960s, the ideological discrepancy between China and North Korea is also becoming increasingly obvious. While Beijing is pursuing “a new type of great power relations,” with Washington, Pyongyang is still obsessed with “American imperialism,” and sticks to its Juche ideology of self-reliance.

“Although both countries are socialist, their differences are much larger than those between China and the west,” Deng Yuwen, deputy editor of the journal of the Central Party School of China, wrote in Financial Times on February 28, 2013. Similarly, Wang Hongguang, a former deputy commander of the Nanjing military region, wrote in the Global Times newspaper in 2014, “Now there is no more ‘socialist camp.’” In response, Rodong Sinmun, the official newspaper of the Workers’ Party of North Korea, publicly denounced these articles as “an extremely ego-driven theory based on big-power chauvinism [of China].” It also warned that, “China should no longer try to test the limits of the DPRK’s patience.”

Sino-DPRK relations today are at the lowest point since the Cultural Revolution, when Chinese Red Guards openly criticized North Korean leader, Kim Il-sung. Due to this increasing ideological discrepancy and mistrust in China, North Korea under Kim Jong-un’s rule has been trying hard to minimize China’s influence over its politics, especially its foreign policy. This is clearly demonstrated every time Pyongyang turns a deaf ear to Beijing’s criticism of its consecutive nuclear provocations. It is true that North Korea is heavily dependent on China economically. But just as Beijing did not give up its nuclear armament even under the terrible economic conditions caused by the Great Leap Forward and the Sino-Soviet split, nor will Pyongyang, even under China’s full and sincere participation in economic sanction. Instead, it will further strengthen Pyongyang’s isolation mindset and belief that the only source of security it can rely on is nuclear weapons. Pyongyang already unequivocally stated, “The DPRK will never beg for the maintenance of friendship with China, risking its nuclear program… no matter how valuable the friendship is.”

Indeed, China’s leverage on North Korea is a lot more limited than widely assumed. Trump’s continuous criticism of China will not yield satisfactory outcomes.

Son Daekwon is a Ph.D. Candidate at Peking University and a Korea Foundation Fellow at Pacific Forum CSIS.