Ahead of the next round of Asian summitry led by the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN) set for Manila later this week, reports have surfaced that, as expected, ASEAN countries and China will endorse a framework on the code of conduct (COC) in the South China Sea that had first been agreed to in May.

Even though we ought to recognize any amount of diplomatic progress, however small, when it comes to the contentious South China Sea disputes, we also need to keep things in perspective by asking: what does the so-called ASEAN-China draft framework on a code of conduct in the South China Sea actually mean, and to what extent does it matter?

Three main things are clear in this respect: there is no real meaningful breakthrough between Southeast Asian states and Beijing on the South China Sea; there is no real code of any kind to speak of; and even if this agreement is built out, evidence suggests it will do little to regulate actual Chinese conduct in the maritime realm.

In other words, the draft framework as it stands now, and even an eventual, concluded COC for that matter, may not really matter that much if the past is any guide to how the future will play out.

No Real China-ASEAN Breakthrough

First, there is no real breakthrough between China and ASEAN states on the South China Sea. Instead, what we have seen thus far is more of the same.

China’s trumpeting of a new “cooling down” period in the South China Sea is nothing new. It is consistent with its tendency to calibrate its maritime assertiveness between coercive actions to enforce its extensive claims and periods of charm to consolidate gains it has made and to manage the losses it has incurred with ASEAN states, major powers, and the international community (See: “Will China Change its South China Sea Conduct in 2015?”). Or, as one Southeast Asian official in an ASEAN claimant state put it to me much more darkly in a candid conversation last summer, “like an abusive husband” with the repeated cycles of hits and makeups.

It is no coincidence, for instance, that China only conceded to a non-binding Declaration on the Conduct of Parties (DOC) in 2002 after it had executed the first seizure of a feature from an ASEAN member state (Mischief Reef from the Philippines in 1995) and had tested the resolve of Southeast Asian states as well as Washington and encountered more pushback than expected.

Similarly, China is now playing up this “cooling down” period after both completing its island-building activities and sensing that a number of fortuitous events – most notably the weakening of the Philippine South China Sea position under Rodrigo Duterte – gives it a way to “turn a page” (to borrow a favorite phrase among Chinese officials over the past year) from the humiliating defeat in last year’s arbitral tribunal ruling (See: “Beware the Illusion of ASEAN-China South China Sea Breakthroughs”).

Meanwhile, Beijing has shown no signs of departing from its decades-long goal in the South China Sea: to acquire the capabilities and to undertake calibrated actions that will allow it to eventually enforce its extensive (and now unlawful) claims in the South China Sea at others’ expense while not entirely alienating neighboring states and jeopardizing its rise.

China’s construction of military facilities on the Spratly Islands has continued, along with other familiar sorts of behavior such as the coercion of other claimant states (most notably Vietnam on energy exploitation) and pressure on other regional and extraregional states not to “interfere.” Meanwhile, Chinese leaders continue to restate, as President Xi Jinping did this week at his speech during the 90th anniversary of the People’s Liberation Army (PLA), that China will not cede an inch of territory, a rather unhelpful stance as it only hypes up nationalist sentiment at home and makes agreements like joint development harder to strike abroad.

We are seeing more of the same from ASEAN states as well. Beyond the diplomatic niceties, claimant countries and interested parties, to varying degrees and though still being aware of their limitations relative to China and the divisions within ASEAN, continue to speed up their own unilateral, bilateral, and minilateral steps to safeguard their interests while acceding to the slow progress in the multilateral realm that Beijing has agreed to.

There is no doubt that Duterte’s seemingly sudden about-face on the South China Sea during the Philippines’ ASEAN chairmanship, and, to a lesser degree, other factors as well like the uncertainty over the U.S. role under President Donald Trump, have combined to water down the degree of ASEAN consensus for now (though, as I have pointed out previously, this tends to ebb and flow because of the divided nature of the grouping). (See: “The Truth About Duterte’s ASEAN South China Sea Blow”).

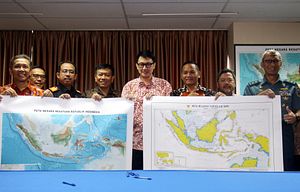

But the steps we have seen from individual Southeast Asian states of late, be it Indonesia’s recent announcement of the North Natuna Sea designation, Vietnam’s attempt at furthering energy exploitation earlier this year, or even for that matter Malaysia’s hardening rhetoric and tougher enforcement against maritime encroachments even as Prime Minister Najib Razak continues to engage Beijing economically, illustrate that we are far from any kind of ASEAN-China understanding or cooling down period of any sort (See: “Beware the Illusion of South China Sea Calm”).

No Real Code of Conduct

Second, there is not yet any meaningful code of any kind to speak of.

The so-called draft framework for a COC is a continuation of a quarter century of “agreeing to disagree” between ASEAN and China on some form of binding framework to regulate conduct in the South China Sea. In that time, a 1992 ASEAN declaration was ignored by China; the quest for a binding COC among some Southeast Asian states in the mid to late 1990s was eventually watered down to a non-binding DOC in 2002; and China has since then been dragging its feet on a binding COC up till recently, with the draft framework introduced this May.

Considering that we are now a quarter century into discussing a framework on the South China Sea and 15 years have passed since the DOC, the draft framework is quite simply an embarrassment. The working version that I had seen was essentially a skeletal one-page outline, consisting of a series of bland principles and provisions, some of which China has already violated, and a few operational clauses – the ones that ought to be the focus of a meaningful, binding COC of any sort – that have been left vague.

Southeast Asian officials familiar with the issue and ongoing discussions no doubt realize that this all amounts to very little substantively. Though there have been a series of sobering analogies I have heard in the region, my favorite came from one diplomat from an ASEAN claimant state at the sidelines of the Shangri-La Dialogue in Singapore this year, who said that this was the equivalent of submitting a table of contents to an editor years after a much-delayed manuscript was expected and then attempting to pass that off as progress.

Of course, this is at least a start, and ASEAN countries and China have been clear that this is a framework to build on, rather than a final document. But that misses the point. The issue is the extent to which diplomatic progress achieved in regulating the conduct of claimants and other relevant actors in the South China Sea is keeping pace with the changing facts on the water, primarily driven by Beijing’s actions.

The past quarter century has shown that the former has proceeded glacially while the latter has advanced blazingly, to the benefit of China and at the expense of other ASEAN claimant states and interested parties like the United States who have a stake in the issue as well. The draft framework does not even come close to changing that grim reality, and it will take a lot more work before it does.

No Real Regulation of Behavior

Third and finally, even if a draft framework is built out and we eventually do see a COC concluded in the distant future, the reality is that it is unlikely to actually help regulate China’s behavior in the South China Sea.

The past quarter-century has shown that China has not just been blatant about its foot-dragging on future commitments, but is equally unafraid to flout commitments it has already made in order to realize its goal of acquiring capabilities and undertaking actions to eventually enforce its extensive claims in the South China Sea at others’ expense.

Even as China continues to call for the full implementation of the DOC – mostly as a delaying tactic to stall the negotiation of a binding COC – it has itself violated the DOC through various actions including land reclamation activities. Other indicators, from Xi’s violation of his pledge in Washington not to militarize the Spratlys to Beijing’s reluctance to comply with the binding arbitral tribunal ruling, also do not inspire confidence in this regard.

Nor, by the way, do the artful diplomatic dodges and endless legal loopholes that Chinese officials and scholars, along with their proponents, continue to use. To seasoned observers, this is nothing more than duplicity under the guise of intellectual masturbation.

Some continue to hope for future shifts in China’s position in this respect, be it an eventual clarification of the notorious nine-dash line or a gradual acceptance of binding frameworks. But that (seemingly endless) wait misses the point. The issue is not whether the extent of Chinese compliance will evolve at all, but whether it will evolve to a degree that will keep pace with the facts on the water.

So far, what we have seen instead is that the elusive quest to regulate Chinese behavior (or to get Beijing to regulate its own behavior) has been vastly overtaken by the facts on the water. If this continues to be the case, even if we eventually get a binding and meaningful COC, it would have been rendered meaningless because Beijing would essentially have de facto control of the South China Sea by then.

Philippine Supreme Court Justice Antonio Carpio, a shrewd South China Sea observer, has been warning that even as the focus is on getting to Beijing to agree on a COC, we should not discount a scenario where China eventually does agree to do this, along with further steps like a freeze by all claimant states on island-building, reclamation, and militarization — once it achieves its objective of assuming control of the South China Sea through steps like reclaiming Scarborough Shoal and developing the capabilities for an effective, enforceable (and perhaps undeclared) air defense identification zone (ADIZ).

In other words, China may indeed accede to the COC once it succeeds in achieving its goal in the South China Sea. And by that time, a COC will not really matter much.

Even as we acknowledge the incremental progress — real or imagined — being touted in the diplomatic realm on the South China Sea disputes between Southeast Asian states and Beijing, these broader realities as important to keep in mind.