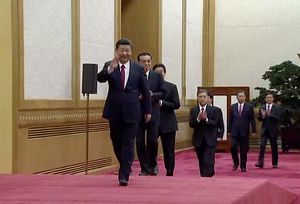

Well, it’s official. The Chinese Communist Party’s new Politburo Standing Committee (PSC) will consist of seven individuals. Listed in order of seniority, they are: Xi Jinping, Li Keqiang, Li Zhanshu, Wang Yang, Wang Huning, Zhao Leji, and Han Zheng.

With President Xi Jinping (now 64 years old) and Premier Li Keqiang (62 years old) continuing on from the previous PSC, the new line up brings five new faces into China’s highest policy making body.

Who Are the Five New Members?

Li Zhanshu has been director of the General Office of the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) since August 2012. Before that, he was Communist Party secretary of Guizhou (2010-2012) and governor of Heilongjiang (2007-2010). He was born in August 1950, and is 67 years old.

Wang Yang has been a vice premier of the PRC since March 2013. Before that, he was Communist Party secretary of Guangdong (2007-2012) and Party secretary of Chongqing (2005-2007). He was born in March 1955, and is 62 years old.

Wang Huning has been director of the Party’s Central Policy Research Office since November 2002, and over the past two decades has served as a key advisor to Jiang Zemin, Hu Jintao, and Xi Jinping. He was born in October 1955, and is 62 years old.

Zhao Leji has been head of the CCP’s Organization Department since November 2012. Before that, he was Communist Party secretary of Shaanxi (2007-2012) and Party secretary of Qinghai (2003-2007). He was born in March 1957, and is 60 years old.

Han Zheng has been the Communist Party secretary of Shanghai since November 2012. Before that, he was mayor of Shanghai (2003-2012). From September 2006 to March 2007, he also served a short stint as Shanghai’s acting Party secretary. He was born in April 1954, and is 63 years old.

What Does This Mean for China?

While most immediate news stories have emphasized the absence of any clear cut successor to Xi Jinping in the new line up and have taken that as a sign that Xi is planning to continue on as China’s leader for the indefinite future (rather than simply oversee the next five years and step away), I read the composition of the new PSC somewhat differently.

I grant that, outside of the new PSC line up, there are a number of indicators of Xi’s considerable strength – for example, the massive reorganization of China’s military and recent promotions, his designation as “core leader,” Sun Zhengcai’s sacking and purge, and the recent change of the CCP’s constitution to include the phrase “Xi Jinping thought on socialism with Chinese characteristics for a new era.” Still, from my perspective, the PSC line up itself seems to indicate both a willingness to defy conventions as well as some respect for institutional norms.

As far as a violation of norms are concerned, the absence of younger, potential successors to Xi on the new PSC breaks with recent practice. In recent decades, successors have generally served on the PSC for at least a term before becoming Party general secretary. When Jiang Zemin began to step down in 2002, Hu had already been on the PSC for a decade, having been elevated in 1992. When Hu Jintao stepped down in 2012, Xi Jinping and Li Keqiang had both already served a term on the PSC. If Xi steps down in 2022, then whoever succeeds him will either be older than expected (unlikely) or will not have served a full term on the PSC (more likely). If Xi does not step down in 2022, then recent norms regarding retirement age and the length of a leader’s time at the top in China will have been violated. One way or another, the lack of successors on the new PSC signals a break from recent precedents.

It should also be pointed out that, from a seniority point of view, Li Yuanchao’s absence from the PSC also runs counter to recent norms. Born in November, 1950, he is only 66 years old (and so, should not have been facing age-related retirement issues). Moreover, at the time of the recent Party Congress, he had already served two terms on the Politburo. On the basis of age and experience then, he had one of the strongest claims for elevation to the PSC (with the only other person in a similar situation being Wang Yang, who did indeed get promoted). Nevertheless, not only did Li Yuanchao fail to get promoted, he lost his position on the Politburo. While his treatment is clearly in violation of recent norms regarding seniority, his serving as vice president without having a seat on the PSC was also unusual, and so, having been marginalized in that way in 2012, his failure to advance this year can’t really be said to be a surprise.

At the same time, the new PSC line up also shows some signs of respect for convention. In particular, all those 68 or older on the PSC retired. This includes Wang Qishan, the youngest retiree at age 69, despite some speculation that he might stay on. In addition, all new faces on the PSC came from the Politburo. Nobody was helicoptered into the PSC, like Hu Jintao in 1992, not even Chen Min’er, despite some talk of such a possibility. Also, Li Keqiang continues to serve as premier and PSC member (despite some whispers that he might be pushed out of his position as premier).

How Did the Congress Compare to Earlier Predictions?

Relative to the lead up to the 18th Party Congress in 2012, there seem to have been fewer commentators willing to go out on a limb and publicly predict who they thought would end up on the PSC after this year’s 19th Party Congress.

That said, last fall in The Diplomat, Chutian Zhou predicted that the 19th Party Congress would result in a PSC line up of Xi Jinping, Li Keqiang, Wang Huning, Sun Zhengcai, Wang Yang, Hu Chunhua, and Zhao Leji or Li Zhanshu. More recently, on October 12, Miles Kwok (Guo Wengui), who has made a name for himself by revealing explosive but unsubstantiated accusations of CCP corruption, tweeted out his own list of individuals he claimed would comprise the new PSC: Xi Jinping, Li Keqiang, Wang Yang, Han Zheng, Hu Chunhua, Li Zhanshu, and Chen Min’er.

To Zhou’s credit, he correctly predicted five out of seven members of the reconstituted PSC a year in advance of the event. Just weeks before the event, Kwok did no better. Zhou did not foresee the purge of Sun Zhengcai. Kwok was too optimistic about Chen Min’er’s ability to advance (while Chen wasn’t elevated to the PSC, he was promoted to the Politburo). In both cases, the biggest error came in assuming the new PSC would include younger potential successors to Xi Jinping. As evidence of the failure of conventional expectations, the lack of successors is clearly newsworthy.

As far as my own work is concerned, I considered three potential scenarios in The Diplomat last year: a base case built purely on institutional norms, a “compromise” case, and a third case representing a dominant Xi. All three cases included Xi Jinping, Li Keqiang, and Li Zhanshu as PSC members, and as it turns out, all three ended up on the new PSC (not a particular reach in the case of Xi and Li). Overall, the institutional base case successfully accounted for four out of seven members of the new PSC, while the compromise case captured six of the seven, as did the case representing a dominant Xi.

Clearly, the results go beyond what can be understood by institutional norms alone. Whether the results are more indicative of political horse trading and compromise or a triumphant and unconstrained Xi is less clear. On one hand, the elevation of Wang Yang and retirement of Wang Qishan appear to be evidence of there being some constraints on Xi’s power. The failure to promote any younger potential successors to Xi and Li Yuanchao’s retirement, however, speak to Xi’s ability to go beyond convention.

What Comes Next?

While there is some uncertainty as to how things will shape up, it appears that Li Zhanshu is likely to become chairman of the Standing Committee of the National People’s Congress and that Han Zheng will become chairman of the Chinese People’s Political Consultative Congress (CPPCC). Zhao Leji will be in charge of the Central Commission for Discipline Inspection (CCDI), and Wang Huning is likely to be in charge of ideology and propaganda, while Wang Yang will become senior vice premier.

If Wang Yang ends up as the first-ranked vice premier, he seems well positioned to become premier in 2022.

While some may make much of Zhao Leji replacing Wang Qishan as head of the Central Commission for Discipline Inspection (since new hands could mean a change in the way corruption charges have been handled), I think there may be less to this than meets the eye. If recent reports on restructuring are to be believed, then – as I noted this past spring – the NPC looks set to become an umbrella organization covering the CCDI and other inspection agencies. With Li Zhanshu, Xi Jinping’s “most trusted ally” expected to head up the NPC, will we see a case of plus ça change, plus c’est la même chose?

Meanwhile, Xi seems to be grooming Chen Min’er for higher things.

In symbols and substance, Xi is powerful. While he may have thrown some bones to others in this latest round, he seems to be astute at dealing with rivals. While I don’t think Xi will decide to keep his seat on the PSC or his current positions as CCP general secretary after the next Party Congress in 2022, he may well continue to hold considerable power after 2022 and could easily continue on as chairman of the Central Military Commission (CMC). That said, Xi’s first five years in power have coincided with a relatively tranquil international environment and world economy. Whether he is able to navigate as deftly in times of stress remains to be seen.

Jonathan Brookfield is an Adjunct Associate Professor at the Fletcher School of Law and Diplomacy at Tufts University. His research covers politics, economics, and business strategy in Asia.