If we have to choose a single word for Chinese politics since the Qin Dynasty (221-206 BCE), the first central government established in China, that key word should be “succession.” With no parliamentary democracy and popular elections, the succession of current leaders became the number one problem for the different generations of rulers in China — from the emperors of the dynasties, to Chairman Mao, and to the current President Xi Jinping.

Even though Xi will surely be reelected as the number one leader of the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) in the upcoming 19th Party Congress, which will begin on October 18th, the most important issue for this congress is still succession. This is about whether the congress will follow the recent norm to choose someone as a successor to replace Xi in five years at the next party congress in 2022, or if Xi wants to become China’s Putin, and have more than two terms in power as the top leader.

For the Chinese emperors during the different dynasties, the succession system was based on blood — the emperor passed his position on to his son, and the son to the grandson, and so on. Normally the priority of succession goes to the eldest son, but when the emperor has multiple sons and the eldest son is not the most talented or suitable, the selection could be a complicated process. It involved the current emperor’s evaluation of his different sons, and the different son’s mothers and relatives would be involved in the process as well.

Looking back at the history of China, it is not an exaggeration to say that succession has been a main theme of internal Chinese politics. Each dynasty had its own succession stories, and most of them were tragedies — many different court plots, murders between brothers and royal families, and civil wars. These stories about the struggles for succession have been made into operas, movies, and novels for generations of Chinese.

Emperor Yongzheng, a powerful emperor of the Qing Dynasty, was tired of the internal struggle of succession, so he created a very special system. He wrote the name of his chosen successor in a formal document, and placed it on a plaque above a door in the main hall of the Forbidden City where no one could reach it. After Yongzheng died, the document could be retrieved, and the rightful successor would be revealed. The reason for the emperor to do this was to avoid the negative consequence of infighting between the princes, very often the chosen prince would become the target of attack from the other sons. Also, a selected prince very often would attract a large group of officials seeking to establish themselves with the future ruler, which would make the current emperor a lame duck. So Yongzheng’s method had multiple advantages in helping to avoid such consequences as murder, infighting, and marginalizing the current leader. This special way of choosing successor invented by Yongzheng had been used for nearly 200 years.

After the CCP came into power in 1949, the question of succession was still the number one political issue. To some extent we could say the succession issue has been the main source of conflict for each of the main internal power struggles of the party, from the Cultural Revolution to the Gang of Four in 1976, and the 1989 Tiananmen movement.

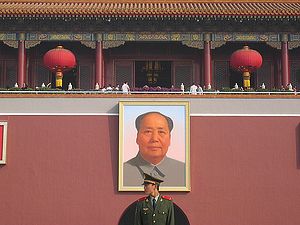

Succession was the dominant issue during Chairman Mao’s term. Mao initially chose two successors: Liu Shaoqian and Lin Biao. But his conflict with Liu became one of the main sparks behind the outbreak of the Cultural Revolution in 1966, and before he could remove his second successor, Marshall Lin Biao, Lin and his family members boarded a flight to the Soviet Union which crashed in Mongolia, killing all aboard on September 13, 1971.

Chairman Mao’s death on September 9, 1976 created another huge crisis of succession. On October 6, Hua Guofeng and Marshal Ye Jianying arrested Mao’s widow and several of her allies.

When it comes to Deng Xiaoping’s time, the same story repeats itself. Deng also chose two successors, but he ended up removing each of them. The succession issue was a major reason for the escalation of tensions in 1989. Deng finally used extreme methods, and sent troops to remove the students from Tiananmen Square. He also placed his second successor, Zhao Ziyang, under house arrest.

Realizing the huge possible damage that could be created by the succession issue, Deng later created a new system for the party. This is called Gedai Zhiding in Chinese. Basically, the current leader chooses his successor’s successor. The current leader can’t choose his own successor, avoiding the dominance of power and the dictatorship. But the current leader can choose his successor’s successor so the next leader needs to share power with the selected prince. For a period of time this system seemed to work well, and a few Chinese scholars even wrote articles praising the system as a major innovation and advanced political arraignment. The system worked smoothly for Deng transferring power to Jiang Zemin, and Jiang passed power to Hu Jintao, and Hu passed to Xi Jinping. However, this system has its shortcomings and drawbacks. It basically creates two power centers within the party between the current leader and the selected future successor.

Five years ago in 2012, the CCP experienced its most serious political turmoil since the 1989 Tiananmen crackdown. Dramatic events, such as the arrest of the former Politburo member Bo Xilai and Ling Jihua as well as former standing committee member Zhou Yongkang, were part of the internal party struggle. It has been rumored that even Xi Jinping survived two attempts on his life and there was at least one unsuccessful coup plot. Another negative consequence of Gedai Zhiding is it ensures that the party lacks strong leadership. The collective leadership system avoids the dominance of power, but also weakens the top leader’s decision-making. There were strong internal opinions regarding the party which needed stronger leadership, for domestic issues but especially for foreign policy decision-making.

Xi surprised everyone during his first term. He conducted a series of major reforms, and rapidly consolidated power. In the past five years, a large number of Chinese senior officials and senior generals have been removed from their positions. Xi restructured and reorganized the People’s Liberation Army (PLA). Together with his close political ally, Wang Qishan, they launched the strongest anti-corruption campaign since 1949. But the biggest issue for Xi at the 19th Party Congress is still the succession issue.

The political arrangements set in the 18th Party Congress was still based on the Gedai Zhiding system. Hu Jintao selected not one, but two successors for Xi Jinping. Based on this arraignment, Hu Chunhua, the current party secretary of Guangdong, would replace Xi at the party congress in 2022, and Sun Zhengcai, the former party secretary of Chongqing, would become the next premier in 2022. Based on this arrangement, the 19th Congress should be a ceremonial event for these two to enter the standing committee of the Politburo to begin their 5-year on-site training. However, this arraignment is definitely against Xi’s interests, and it can be argued that he doesn’t want to retire five years from now. Just a few months ago people read the striking news that Sun Zhengcai was removed from his position and put under investigation.

With only one week before the 19th Congress, there are all different rumors about the power arraignments and who will ultimately be on the standing committee. The most important thing to watch is the paths of two people: first is whether Hu Chunhua will enter the standing committee and be placed in a position as the next successor, and second is whether Wang Qishan will retire or not. For China, the succession is not only for the top leader. In the collective leadership system, the successor to the position of premier and the successor to the person in charge of discipline, as well as the other positions such as the person in charge of the daily work of the party are all very important. It is not a succession for just one position, but rather succession for a team. This is the reason the membership of the standing committee is so important.

Every five years, it has become somewhat of an intellectual game for the Chinese, especially those interested in politics, to guess who will be named to the standing committee of the Politburo. Its membership is normally seven people, but occasionally it has been nine or five. It’s a challenging game as there are many factors and variables that influence the final list. People who do the guessing have to make judgements based on their understanding of the power struggle among the leadership, and the possible compromise between the different political groups. They also need to be sensitive to any minor indicators of political activities before the party congress.

So I will submit the following name list as my best guess for the standing committee for the 19th party congress:

Xi Jinping, Li Keqiang, Wang Qishan, Wang Yang, Wang Huning, Zhao Leji, Han Zheng

I based my list mainly on seniority. Seniority for Chinese politicians is based on how many terms they have served as Politburo members, and how many terms they have served as members of the central committee. Based on seniority, Hu Chunhua is more junior than Han Zheng, the party secretary of Shanghai, even though both of them served only one term as a Politburo member — in terms of the central committee membership, Han has served three terms, while Hu only served two terms.

Besides seniority, I also excluded a few people who have been widely considered to have no political future, such as the current Vice President Li Yuanchao. The reason I use seniority as the most important criteria is because when the top leadership has major differences on succession, seniority is the most convenient and acceptable criteria for the leadership to use. This is also the reason that five years ago seniority was the only thing that could explain why each member of the standing committee was promoted. Even though there are very strong power struggles among the different political groups inside the party, they are also trying to stay afloat, and not to rock the boat too much.

The final result of the 19th Congress will give us very important information in understanding the communist party’s top leadership and the next five to ten years of Chinese politics. This is important not only for domestic politics but China’s foreign policy. Many people believe that if Xi can successfully consolidate power, especially if he can propel himself past two terms, then during this second term he would be in a good position to carry out more dramatic actions and plans, including many new foreign policy actions.

For China, everything will restart on October 18th.