Last week the U.S. Navy released summaries of the investigations it conducted on the collisions of two Japan-based destroyers earlier this year, resulting the drowning deaths of 17 sailors when their berthing spaces flooded from the impacts. The USS Fitzgerald was struck by the container ship ACX Crystal in the approaches to Tokyo Bay in June and the USS John S. McCain was hit by the Alnic MC barely two months later in the busy approaches to the Singapore Strait.

In the aftermath, both ships’ captains and executive officers were fired, and several other officers and sailors faced administrative punishment. Higher up, the commodore in charge of the squadron the two ships belonged to was fired, as was the admiral in charge of the carrier strike group they were a part of, and the three-star admiral in charge of the Japan-based 7th Fleet. Both the three-star admiral in charge of equipping and training the surface fleet and the four-star admiral in charge of the entire Pacific Fleet are retiring early.

The vice chief of naval operations has also appointed Admiral James Caldwell, who is in charge of the U.S. Navy’s nuclear power program, as the Consolidated Disposition Authority for all future disciplinary actions related to the two mishaps. This move gives Caldwell the authority to initiate additional administrative actions against responsible individuals, or even refer them to court martial for possible judicial punishment.

The results of the U.S. Navy’s investigation into the USS Fitzgerald’s collision are analyzed here. In follow-on posts I will similarly analyze the USS John S. McCain investigation and the corrective measures advocated in the Navy’s also newly released Comprehensive Review of training and seamanship practices in the surface fleet.

Exhausting Schedule Preceded Collision

The day leading up to the mishap was a busy one for the Fitzgerald, full of training and assessments by inspectors certifying the ship’s ability to conduct various operations. The ship got underway from its homeport of Yokosuka, a U.S. Naval base about 20 miles south of Tokyo, at lunchtime, and proceeded to a nearby anchorage to onload new munitions from a barge for three hours. Upon completion, the Fitzgerald again got underway and proceeded the rest of the way out of Tokyo Bay, transiting for several hours to another nearby bay known as Sagami Wan that is often used for training and at-sea assessments by Yokosuka-based ships.

Source: US Navy

For nearly the next four hours the ship practiced landing and launching helicopters from its flight deck, stretching well past sunset and completing around 9 p.m. The ship then spent two hours operating small boats to ferry the inspectors who had been watching the flight operations back ashore so they could return to Yokosuka. At this point, much of the ship’s crew and officers had been conducting intense and often stressful operations for more than 10 hours. The ship’s commanding officer and executive officer had been on the bridge themselves overseeing those operations for most of that time.

Poor Judgement, Neglect of Procedure as Warship Proceeded

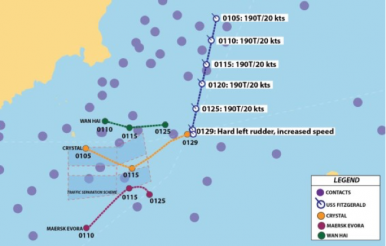

Then, just after 11:00 p.m. and with a normal watch now in charge on the ship’s bridge, the Fitzgerald proceeded southwest out of Sagami Wan. It hasn’t been disclosed what Fitzgerald’s destination or follow-on mission was, but despite dense fishing and cargo ship traffic in the area, the Fitzgerald soon increased speed to 20 knots. The investigation determined this speed to be faster than was safe for the situation.

Not only do most commercial vessels transit at much slower speeds, between 10 and 15 knots, but the Fitzgerald’s southerly course meant it was traveling across the prevailing traffic, most of which was moving easterly toward Tokyo through a maritime traffic lane. The Fitzgerald’s charts did not display the traffic lane and the ship’s navigator does not seem to have been aware of its existence when laying out the ship’s course out of Sagami Wan. If it had been taken into consideration, the Fitzgerald would likely have taken a different, safer track to cross the prevailing traffic.

Even before encountering the ACX Crystal, the Fitzgerald’s officer of the deck, the officer in charge of safe navigation on the bridge, violated standard watchkeeping procedures, best practices, and international rules for avoiding collisions.

Upon leaving Sagami Wan the Fitzgerald crossed ahead of three other vessels by less than the three nautical miles (6000 yards) that is standard practice in the U.S. Pacific Fleet where practicable; one vessel was crossed at only 650 yards. The officer of the deck did not report any of these other vessels to the ship’s captain as required by his standing orders to watch standers. Nor did the bridge team assemble the minimum information on any of those vessels that is required to make a sound determination of whether they posed a risk of collision, such as how far away the ship is, its course and speed, how close it will get, the angle that will be between the two ships when they are at their closest, and which of the nautical “rules of the road” apply to the situation. Investigators found that the radar being used on the bridge was not tuned correctly and was not reliably tracking those other vessels.

Watch standers then repeatedly made errors correlating what they saw on their radar with what they saw through their binoculars. Despite the improperly tuned radar and failing to perform the calculations manually, the Fitzgerald’s officer of the deck believed that they would pass no closer than 1500 yards to the Crystal.

The Fitzgerald was on the ACX Crystal’s port (left) side as it approached. This meant that, according to the international “rules of the road” that govern the interaction of ships at sea to avoid collisions, the Fitzgerald was obligated to take action to keep out of the other vessel’s way. The rules also stipulate that Fitzgerald should have done so either by slowing, turning to the right, or both.

It is consistently drilled into U.S. naval officers training to be deck officers to never turn left to avoid another ship in a crossing situation, barring some extraordinary circumstance. Once it became clear that the Fitzgerald’s officer of the deck’s estimate of a 1500 yard passage was wrong, their initial decision was to turn right to attempt to pass behind the ACX Crystal. But then, from the diagrams provided, it seems that the officer was worried that they would not be able to safely get around another, unidentified vessel that was still between the warship and the Crystal, leading them to reverse themselves and order an increase to full speed and a drastic left turn to attempt to cross ahead of the container ship instead.

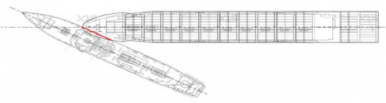

Despite the officer of the deck’s order, there was an unexplained failure by the helmsman, who controls the ship’s wheel and throttle, to execute either the left turn or speed increase until a more senior enlisted watch stander took over the helm and began the turn. However, neither the order nor its execution came in enough time to avoid the Crystal, and at 1:30 in the morning the larger vessel struck the Fitzgerald at about a 45 degree angle, crushing part of its superstructure and puncturing its hull below the waterline.

Source: US Navy

The collision came less than five minutes after the officer of the deck realized that the Crystal posed a serious risk, and only two minutes after their decision to reverse the Fitzgerald’s turn. At no point did anyone inform the warship’s captain of the approaching danger, nor did a more senior supervisor in the ship’s Combat Information Center where the ship’s radars, weapons, and communications equipment are directed, intervene to ensure the bridge was making sound decisions.

By the time the left turn and speed increase were finally executed, the best course of action was probably to remain on the Fitzgerald’s original course and attempt to speed ahead of the oncoming container ship. It is difficult to tell from just the information provided, but since turning bleeds off speed relative to an approaching ship, it is possible that had Fitzgerald not attempted to turn either left or right, much less both, that it might have just barely squeezed ahead of the ACX Crystal. But if the officer of the deck had used sound judgment earlier, such a gamble would not have been necessary to consider.

Instead, even though there was a third vessel complicating the situation, the Fitzgerald should likely have stuck to its original right turn, attempted to cut between the Crystal and that other vessel, and then passed behind the Crystal. But long before even that decision became necessary, the Fitzgerald’s officer of the deck owed it to the ship’s captain to make him aware of approaching vessels and give him the opportunity to bring his own experience and judgment to bear on the increasingly dangerous situation.