This post contains spoilers for Star Wars: The Last Jedi.

Did the writers of the Star Wars: The Last Jedi take some inspiration from the history of the Communist Party of China? The Star Wars Universe notably lacks in many of the throw-ins that modern blockbusters increasingly include to attract Chinese audiences. The ahistorical nature of the universe makes it difficult to directly reference Chinese themes, or develop Chinese characters (to date only Donnie Yen, in Rogue One, has had an extensive role in a Star Wars film).

But intentionally or no, the latest Star Wars film is built around a conflict that may feel very familiar to Chinese audiences. In The Force Awakens, the First Order destroys the vestiges of the New Republic, and inflicts catastrophic damage to the Resistance, a loosely allied organization. In The Last Jedi, First Order forces destroy a rebel base, then pursue the remaining elements of the Resistance to a small, dusty world where the latter make a last stand, hoping for outside assistance. The last stand fails, but a residue of the Resistance survives and escapes the planet on a broken down freighter.

The closest real-world analogue to the experience of the Resistance and the Rebel Alliance may be that of the Chinese Communist Party. The founding mythology of the CCP is well known; only twelve members (enough to fit on the Millennium Falcon) attended the first party meeting in 1921. The CCP came into existence in the years after the collapse of the Qing Dynasty, with contending forces fighting for supremacy. A brief alliance with the Nationalist Party led to some success against warlords, but in 1927 the alliance broke; in the wake of the Northern Expedition, Chiang Kai Shek turned on the CCP, massacring thousands of communists in Shanghai. Similar massacres took place in other parts of the country, resulting in the elimination of almost two-thirds of the CCP’s strength.

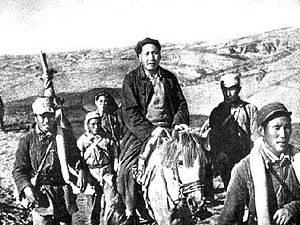

The CCP fled to “hidden” bases around the country, including Jiangxi. In 1934, the Nationalists once again put the CCP on the run, forcing Mao Zedong and his small band of rebels to engage in the Long March, ending in the dusty, distant city of Ya’nan. It is not at all difficult to see echoes of the Ya’nan period throughout the new trilogy, and even the old. Indeed, the pursuit that constitutes The Last Jedi might well evoke the Long March. The film ends with a residue of the Resistance surviving, but with the hope that it can offer redemption to the greater portion of the galaxy that remains under the boot of the First Order, as well as self-interested warlords.

Societal myths often frame our understanding of artistic works. JRR Tolkien insisted, explicitly and repeatedly, that The Lord of the Rings series was not intended as a metaphor for the Second World War. Nevertheless, readers almost immediately perceived parallels between Saruman and Mussolini, Sauron and Hitler, Helms Deep and the Battle of Britain, and the One Ring and the atomic bomb. Even if the authors of The Last Jedi did not intend to echo the experiences of the Long March, Chinese viewers may perceive those parallels on their own.