Bruised and with her arms bandaged, Zulekha squats next to a heap of rubble. The debris used to be a mud house atop the mountain that houses Churanda, a village in the extreme north of Jammu and Kashmir. Beyond the mountain, within walking distance — although no one would dare to walk there — lies the Line of Control (LoC).

India and Pakistan share a 3,252 kilometer border, of which 767 km forms the LoC that runs through Jammu and Kashmir, dividing it between India and Pakistan.

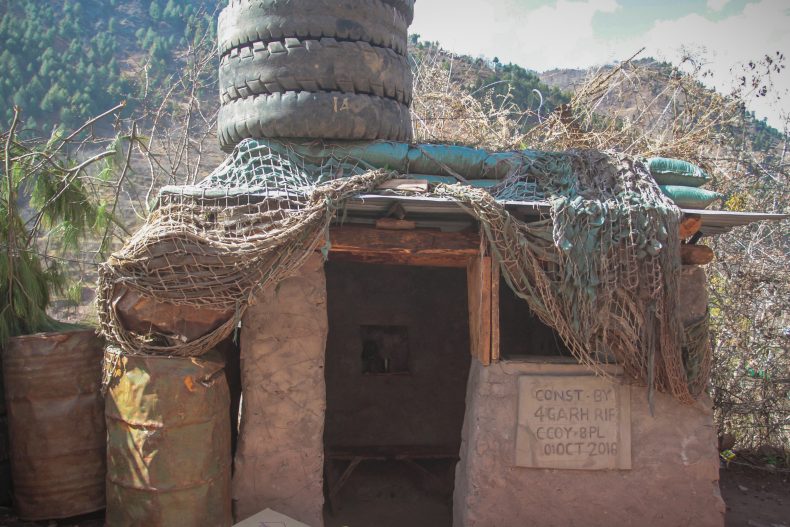

The military installations of both the armies on either side of the LoC can be seen, with the troops peeping through the highly guarded bunkers, ready to shoot at anything they see moving into the territory they are holding on.

Fencing near the Line of Control that divides Kashmir between India and Pakistan at Silikote. The area is witnessing heavy shelling after the hostile situation on the borders between India and Pakistan. Photo by Shuaib Masoodi.

The rubble next to 48-year-old Zulekha was her home until February 19, when a mortar shell from across the border razed it. A few flinders hit Zulekha too, injuring her grievously.

Zulekha was among three people who were injured as a result of firing and shelling exchanged between Indian and Pakistani troops along the LoC on February 19.

In recent years, the Indian and Pakistani armies have engaged in furious exchanges of mortar shells and gunfire. Amid the routine battle on the LoC, the villagers living next to the border are defenseless against the bullets and shells.

The recent flare-up along the LoC began after 17 Indian troopers were killed in an attack in September 2016, when a group of militants, believed to be Pakistani nationals, entered a military base in North Kashmir’s Uri town. The attack came at a time when Kashmir was simmering in protests against the killing of militant leader Burhan Wani and nearly 100 civilians by the Indian forces.

When Zulekha was injured, both India and Pakistan blamed each other for violating the ceasefire that was agreed upon in 2003. An Indian defense spokesman said the attack was initiated from the Pakistani side and “appropriately retaliated by the Indian forces” – a statement that the defense spokesmen and army generals from both sides make every time escalation flares along the LoC.

A family stands near a hole in their ceiling, through which a shell fell into the house in Silikote, Uri. Photo by Shuaib Masoodi

The day Zulekha’s home was reduced to rubble marked a new spell of cross-border tension.

A treacherous one-and-a-half hour trek down the mountain leads to Tilawaadi village, where a few mud and concrete houses sprawl under the constant gaze of Indian army.

There, Subhan Najar, 42, points toward the military installations. “When shells miss these bunkers, they hit our homes.”

Najar was sitting with his family in his house on February 22 when a mortar shell penetrated through the wall and damaged it completely. It was miraculous that all of them escaped alive, he says. Now all that is left behind is charred wood, burnt bricks, and his children’s notebooks, buried under the rubble.

That day Najar heard the loudspeakers blaring from the mosques on the Pakistani side asking these villagers to evacuate as they were going to start shelling.

As most of the villagers evacuated in haste, taking with them a few precious items and leaving behind everything else, Najar decided to stay put.

“I could not leave. Where else could I go, leaving behind my home and cattle?” he asks.

An elderly man clears his room after shelling in an area in Silikote, Uri. Photo by Shuaib Masoodi

Prior to the 2003 ceasefire agreement, the locals in these border villages had built mud bunkers, where they would take refuge every time the two armies along the border engaged in shelling and firing at each others’ post.

These bunkers would cushion the shocks and were hard to penetrate, unlike concrete houses.

But after an earthquake in 2005 razed every structure on either side of the LoC, these bunkers collapsed. As the ceasefire had been agreed upon by both the countries two years prior, the locals were in no rush to rebuild them.

Ever since tensions flared up anew, the locals say, “We have been asking the government to build bunkers for us. At times like these, we can sneak in those bunkers and save our lives even if the houses are damaged. At least we will not have to abandon our livestock and live in cramped places as refugees,” Najar says.

An empty bunker of the Indian Army in Silikote, Uri. The bunker was abandoned after heavy shelling on the borders between India and Pakistan. Photo by Shuaib Masoodi.

This year’s escalation along the LoC is the worst in recent memory. On March 5, Indian Minister of State for Defense Subhash Bhamre accused Pakistan of violating the ceasefire agreement as many as 351 times since January 1 of this year. He claimed that 209 violations took place in January and 142 violations were noted since February 21.

In 2017, as many as 12 civilians were killed and 79 injured due to cross-border firing, Indian official records claim.

In January alone, eight civilians lost their lives to cross-border shelling and as many as 58 were injured.

These records, however, do not estimate damage to property and livestock, nor so they tell about the constant fear the villagers live in.

When 40-year-old Bilal Ahmad from Silikote, located on the hem of the last mountain bordering the LoC, returned home in March after the shelling ceased a little, he found his cow and and a calf lying lifeless in the shed. Their bullet-torn carcasses faced a wall torn off by shells.

If bullets had not killed them, something else would have, he says.

“The cattle do not die only because of bullets, but when we abandon our homes, there is no one to look after them. They starve to death or die of cold. And if they roam around, they may get tangled in some razor fence and bleed to death,” Bilal says.

A worker distributes food at a relief camp in Uri. People are staying in a school room after they migrated from their villages near the Line of Control to escape shelling. Photo by Shuaib Masoodi

When the fresh battle along the border began this year and people abandoned their homes to take refuge at safer places, the government set up a relief camp in Uri town, almost 70 km north of Srinagar, the summer capital of Jammu and Kashmir.

Thousands of villagers were crammed into a government-run school building where they constantly tried to connect with relatives, not knowing if they had fled, stayed, or were alive at all.

Mukhtar was among the few who did not flee. For over a week, he witnessed the horrors that the shells and bullets caused. Every time bullets were fired, Mukhtar said, it felt as if a thunder reverberated through the mountains. When shells hit the ground or carved into the mountains, the earth beneath shook, like an earthquake.

Mukhtar witnessed dozens of such earthquakes everyday when he was almost alone in the village.

Life along the LoC is not only perilous inside heavily protected military bunkers or mud houses. The threat crawls to every corner of over a dozen villages that border or are close to the LoC. It seeps into the cattle sheds, sprawls across fields, and looms large over schools.

The students in these villages walk for hours to reach a government-run school in Balkote, crossing over rivers and treading treacherous mountains, where one wrong step means a fall.

During the initial days of the fresh escalation, parents were not so reluctant to send their children to school. But as the shelling intensified, the schools saw fewer and fewer students.

Children in Uri stay in a school room after migrating from the villages near the Line of Control. Photo by Shuaib Masoodi

“Being alive is paramount here. Education, job, and everything else comes later,” Habeebullah, who lives in Silikote, says.

And Habeebullah stands vindicated in these villages. Thirteen-year-old Ambreen recalls that she was in her classroom when the shelling rattled the school building. She does not remember the date but she has not returned to her classroom since.

“I cried when I heard the loud bang. Our teacher asked us to duck but we all ran away,” Ambreen says.

Though the tensions along the LoC have eased a little, many parents are hesitant to send their children to school again and the students are also reluctant to go back to classes, fearing they might have to run again from school amid showering shells and bullets.

As the villagers return to their houses, almost every wall, pockmarked by bullets, welcomes them to start a fresh life on the dangerous line that divides Kashmir and everything else.

Qadri Inzamam is a freelance journalist based in Kashmir. His stories have been published in BBC Hindi, Express Tribune, Kindle Magazine, and other publications.

Haziq Qadri is a freelance multimedia journalist based in India. His work has appeared The Guardian, The Telegraph, Huffington Post, Daily Mirror UK, Discovery and its affiliate networks, among others.