Each conference should have at least one brain-disabling paper. You know, the one during which you doze off to recharge your mental batteries, prepare your own paper which will be in the next panel, or check out your mobile phone (don’t forget to sit behind somebody, ideally somebody tall). Recently, the most brain-disabling presentations have been the ones that focus on maps of the Belt and Road Initiative (once referred to as the “New Silk Road”).

I am obviously exaggerating here, but this plague has become so widespread that countering it requires strong language.

PowerPoint Instead of Points of Power

My beef is with the “Xinhua maps” – the rather ridiculous maps that originated with China’s state news agency and were copied throughout much of the media. Even more unfortunately, they were also used by some think tanks and academics.

That a paper, an academic article, or a think tank report contains a map which the author has not prepared but rather downloaded from the internet does not necessarily make the accompanying work bad. But such a map is often like jewelry to the text’s main body: something pretty, meant to raise the status and arouse curiosity, but which says nothing of the owner’s intelligence and work. Otherwise, had the author analyzed some of those “Xinhua maps” he or she would have discovered they do not reflect Beijing’s official agenda and curiously show more of the distant past than the near future.

One simple observation is that the popularity of the Belt and Road Initiative maps comes from intellectual laziness and the pitfalls of internet research. Why waste months and years digging deep into official (and long) Chinese reports, analyzing international agreements and statements, and taking into consideration political, economic, and geographic factors? It’s better to wire into the internet on Sunday evening, copy some media map, and treat it as an official one. Add it to your PowerPoint presentation, sprinkle it with a few facts, add a photo of Xi Jinping, and your conference paper is ready in two hours.

Well, the fact that the maps originated from Xinhua does not make them official. In fact, the official Chinese publications do not agree with the “Xinhua maps.” One could, for instance, consult Building the Belt and Road: Concept, Practice, and China’s Contribution (published in connection with the Belt and Road Forum for International Cooperation held in May 2017) or read the Vision for Maritime Cooperation under the Belt and Road Initiative and compare them with the “maps” displayed below.

However, the above criticism refers only to the “Xinhua maps.” If a center or an individual prepared its own map based in an original and painstaking research then that is a completely different story. For example, Harbored Ambitions. How China’s Investments are Strategically Reshaping the Indo-Pacific, a report by C4ADS authored by Devin Thorne and Ben Spevack, is a big piece of work that resulted in creating informative maps and visualizations. Similarly, a report prepared by Polish think-tank the Centre for Eastern Studies — The Silk Railroad. The EU-China rail connections: background, actors, interests — maps out the extant railway corridors between Europe and China. It is also worth adding that such serious reports show a reality much different from the word of the “Xinhua maps.”

Of course, this is Asia Life and the focus of this section is not on politics or economy. What I will try to show is how our visions of history influence our present thinking. But, of course, all of this does leave an effect of our understanding of politics and economy as well.

The New Chang’an for a New Silk Road

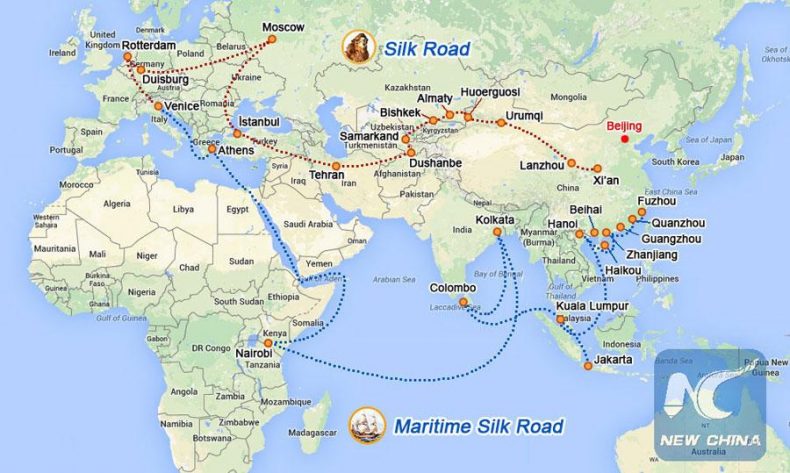

This is the first of two widely used maps I will deal with.

The initial section of the land route is a very clear reference to the historical Silk Road which, more or less, went the same way: from China through Central Asia, to fork out into one road toward India and another toward the Middle East. The trouble is this: what is shown on the map above is the old Silk Road, not the new one.

Current official Chinese publications stress the importance of the land connections between industrial east China with Europe and Russia through Kazakhstan. The above map does not show this trade link. In the future, the connections between Central Asia and Iran may acquire more importance for the Chinese, but for now, contrary to the above map, this is not Beijing’s main focus.

Even the starting point betrays that the map partially lives in a distant past: it shows Xi’an as the beginning of the “New” Silk Road. Unless I missed something, the current Chinese government is neither trying to shift its capital back from Beijing to Xi’an nor make Xi’an the new Shanghai.

Yet, my favorite part of this map is the illogical turn of the route from Istanbul to Moscow, only to return to Europe. But of course: so many traders badly need to pick up something very important from Russia on their way from Turkey to Germany, right? Caviar, maybe? As far as I know, this curve has nothing to do with any official Chinese plans. But it is also unclear to me if this section of the fictional route has anything to do with a historical reference.

Beyond staid historical references, the map simply does not reflect current Chinese activities. The South Asian part of the old Silk Road is not shown in this map at all, for example. The China-Pakistan Economic Corridor (CPEC) is perhaps one of the most measurable, concrete elements of the Belt and Road Initiative and yet this map ignores it altogether.

The “Maritime Silk Road” is also a curious combination of real routes, strangely drawn lines, and a sprinkling of historical references. It does show the industrial coast of eastern China, the strategically crucial Malacca Strait (though it chooses to mark Kuala Lumpur instead of Singapore) and some of the other ports of the Indian Ocean: Calcutta, Jakarta, Colombo, and Nairobi. It would be far-fetched to assume that the choice of these ports must be based on historical references as all of these cities may gain more importance for Beijing in the future (especially the strategically placed Colombo).

Yet, why the map forces the ship to go from Nairobi to Calcutta only to return to Colombo and then to proceed to Jakarta via Kuala Lumpur to take a sharp turn toward China is anybody’s guess.We perhaps should just ignore the sea route as drawn on this map and focus only on the ports. But speaking about this, while the already mentioned Vision for Maritime Cooperation under the Belt and Road Initiative document does mention Colombo Port City and the Mombasa-Nairobi railway line among the implemented projects, the map ignores other very important ports and bases. The chief missing points are the Kyaukpyu port in Myanmar, Hambantota in Sri Lanka, Gwadar port in Pakistan, and the Chinese navy base in Djibouti.

While the ships on this map drift between the continents, stumbling upon an important port from time to time, they do reach Athens, which seems entirely correct, as the Piraeus port is both mentioned in Chinese strategic documents and was taken over by the Chinese company COSCO, which purchased 51 percent of its shares in 2016. Yet, after finally reaching the shores of reality, the map suddenly takes us back to history by leading the route onward to Venice. I guess we are going centuries back to the glory of the Italian trading city, to the period of the pre-Columbian spice trade. The shadow of this historical period will also loom large over the next map.

Marco Polo Would be Proud

Let me now consider the second map, which is, by the way, much more “historical.”

I guess we can never get rid of the idea that Xi’an (Chang’an) is still the capital of China. Else, why would it be marked on this map when so many other cities – like Shanghai – were ignored? Here, however, at least the land route does start/end in Beijing. Moreover, like the previous map, this one again takes us along the old Silk Route by leading the merchants from western China not toward Europe but in the direction of Iran. Forget the trains to London or Amsterdam (forget Europe, in fact) – I guess we are back in the caravans which struggled through the mountains to get the Middle East.

Once again, however, the map does not fully recreate the Silk Route as it does not show the forking of the road toward India. It reflects our reality even less, however, as it also ignores the CPEC. As for why the land route ends in Istanbul I can only have one explanation: I guess Istanbul is still the capital of the Ottoman Empire.

The “Maritime Road” of this map again has much more to do with the pre-Columbian (and pre-da Gama) period of spice trade than with our time. Once again – just like the previous map – it does not show Gwadar, Kyaukpyu, or the Djibouti base. Moreover, it reminds us of the ports that used to flourish in the time when sailors were ready to sacrifice two years of their lives to bring pepper from the Malabar coast and when nutmeg was valued like gold. Hence, the map marks Banda Aceh port, but not Singapore or Kuala Lumpur. It also reminds us of the existence of the long-forgotten Khambhat port in western India. The last time it was important was roughly in the time of Marco Polo and, as far as I know, the Chinese strategic documents make no mention of reviving this small, decrepit port (not that India, which has steadfastly refused to take part in the BRI, would let them).

Marco Polo would be proud of this map, however. Try Googling something like “Venice spice trade.” What you will soon find is a map (or a few) that – accurately or not – shows nearly the same sea routes which the author of this “Xinhua map” perhaps just copied onto his imaginary framework of the Belt and Road Initiative.

The Maps of Our Minds

Beyond those that slavishly forward the maps are the largely anonymous people who invented them. What they created shows not only a disregard to facts but something more deep and general: how much our understanding of the future is shaped by our perspective of past and geography, a perspective that often changes more slowly than the reality around us.

It is not only about redrawing lines on pieces of paper. Let us take the example of Nepal’s geographical position. It is obvious that being born in the shade of the great wall of the Himalayas, Nepal is largely dependent on India for transit. This fact has shaped much of Nepal’s history, culture, and economy and it still significantly affects its present position. And, yet, things do change. While watching the ongoing Indo-Chinese war of influence in Nepal – a struggle which has been going on for decades and in which China, despite the geographic odds, is growing from strength to strength – one can see that there are ways not only to cross the Himalayas, but to bypass their barrier. Not only do planes fly over the mountains but money transfers reach their destination invisibly and swiftly, while the propagators of soft power shape people’s minds through the media and the internet without traveling to their homes.

Most of the maps do not show these aspects because they either physically can’t or because we, as creators of these maps, are not mentally prepared to mark different elements of reality on them. This is something that the prophets of a false religion called “geopolitics” do not understand – geography is obviously always important but its importance changes as human technology progresses.

And so it is with the Belt and Road Initiative. It is not only about the fact that the authors of the “Xinhua maps” partially just copied the old trade routes. More importantly, many people seem to imagine the Belt and Road Initiative as the old trade route reborn. It is not envisaged as an elaborate economic chain but as a simple, medieval, point-to-point transfer of goods and coins (which, by the way, was far from being that simple even at that time).

The world is changing and we do not always catch up with it mentally, and certainly not with the way we perceive it through maps. The Belt and Road Initiative is a good example of this. Whatever can be said about the BRI, it is not only about a train loaded with Chinese-made stuff reaching Germany or a ship from Shanghai reaching Amsterdam. It is does not suffice to simply link two circles on a map with a line. The economy of today is so much more complex. There are global chains of productions; national, subnational, and international-level tariffs; economic zones; shares in companies; and so much more. Some of these aspects may be too difficult and too different in character to be put on a map – or maybe we just need creative people that will design new, and original, maps. The Belt and Road Initiative is so complex, differently interpreted, and dynamic — incorporating new projects all the time — that we should look for new, innovative ways to represent it geographically.