The curtains have come down on Wuhan, arguably the largest and most talked-about meeting between two heads of state, giving keen competition to the historic meeting between North Korea’s Kim Jong-un and the South Korean President Moon Jae-in in the demilitarized zone (DMZ) between the two countries.

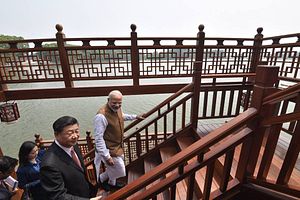

The Indian media has been understandably gung-ho about the “reset” in bilateral ties, while the Chinese media, equally predictably, has been as positive as they are allowed to be. Wuhan yielded no joint communiqués, as the meeting was supposed to be an “informal” summit, with no set agenda. A boat ride, a walk along the East Lake and a visit to the Wuhan Museum – all in Chairman Mao’s erstwhile summer resort – provided colorful optics to what has been marketed as a freewheeling chat, between the leaders of two neighboring countries which have, historically, tended to rub each other the wrong way.

The idea for Wuhan was born in the wake of the 72-day long standoff in Doklam in 2017, when Modi told Xi, on the sidelines of the G20 Summit in Hamburg in July, that the two countries should not be talking at each other, but to each other, especially given the (formidable) range of concerns each share about the other. India and China have always had a complicated relationship, often with one step forward being hindered by two steps backward. But the thorn in the side for both countries has, then and now, been the 3500-km long boundary that they share, which covers sectors that are the source of constant dispute and suspicion, not to mention incessant border transgressions.

With the growth of globalization and regional connectivity, other issues have sprouted: India’s open antagonism towards China’s Belt and Road Initiative (BRI), particularly towards the China-Pakistan Economic Corridor (CPRC); its attempts to counter rising Chinese influence in the Indian Ocean and South Asia by moving closer to the United States, Japan ,and Australia; Beijing’s hackles rising at India’s bid to enter the Nuclear Suppliers Group (NSG); and concerns over terrorism.

Wuhan — with its several rounds of talks between Modi and Xi — was an attempt to try and bridge the bilateral strategic communication gap. Even before the summit began, Indian officials warned watchers not to expect agreed outcomes. The focus was, ostensibly, to discuss issues on a macro-scale, from terrorism to climate change, from connectivity to dealing with the changes in the international scenario.

By those standards, one might term Indian Foreign Secretary Vijay Gokhale’s press briefing predictable. The official press release, from India’s Ministry of External Affairs, is even more anodyne, reiterating much that has already been heard before. The two sides have agreed to expand cooperation on trade, technology and climate change. Both Xi and Modi recognize the common threat posed by terrorism, and have committed to cooperate in the field of counter-terrorism as well. The two sides have also underscored the fact that, given their greater and overlapping interests, there is a definite need to keep communications at the highest levels open and flexible.

The only new development, which might come as a blow to Pakistan, is the fact that India and China have also agreed to start discussing the modalities of a joint economic project in Afghanistan, in addition to the possibility of further regional economic collaboration. Communications about the border will continue via the Special Representatives of both countries, and strategic guidelines will be issued to both militaries to ensure the expansion of communications along the border, with the long-term aim being to minimize the occurrence of any future Doklam-like incidents.

Will Wuhan provide a new way forward for bilateral relations? If Modi’s statements, post-Wuhan, are anything to go by, he would like to continue with this format — Xi has already been invited for a similar summit in New Delhi in 2019. The answer lies somewhere in the middle. Certainly a meeting of this kind is a step towards mutual reassurance, and it signals an outward willingness to sit down at the same table and discuss existing problems. Shen Dingli, a professor of International Relations at Fudan University, and currently one of China’s leading foreign affairs experts, was carefully neutral in a recent interview, saying that summits such as these neither hurt nor help relations as they stand.

Indeed, prior precedents of summits such as this are not exactly winning examples – both China’s informal meetings with the United States, in 2013, and in 2017, failed because reality did not keep pace with optics. For Obama in 2013, it was cyber-security that was the bugbear, and for Trump in 2017, the deal-breaker was trade. What’s more, in 2013, while Modi and Xi were amiably sharing a jhoola (swing) in Gujarat, Chinese troops were crossing the border.

Indeed, for India, the border remains at the heart of its relationship with China. The official press release states that peaceful discussions are the way forward, “bearing in mind the importance of respecting each other’s sensitivities, concerns and aspirations.” In itself, this statement is a loophole, and provides a potential stumbling block, to be set up as and when required. Nor, according to Gokhale, did the two leaders go into “specifics” about the issue of Jaish-e-Mohammad chief, Masood Azhar. Equally ominously, China has stated that it does not believe that India has changed its official position — that Tibet is part of China.

As far as the BRI is concerned, China has agreed not to be too inflexible about India’s involvement. Vice Foreign Minister, Kong Xuanyou, has been quick to state that China does not have any fundamental difference with India when it comes to inter-connectivity, and if India does not like the expression “Belt and Road”, China will not push for its acceptance. But this, while appearing to be magnanimous enough, does nothing to assuage India’s own concerns about possible territorial encroachments in an already troubled area.

In his interview, Shen Dingli, when asked if India should soften its opposition to the BRI, was brutally (and tellingly) honest. “If I were Indian, I would not soften my position.” In technical terms, a “reset” implies a complete start from scratch. In the case of India and China, there is, perhaps, too much history for this term to apply.

Narayani Basu is an author and independent journalist, with a special interest in Chinese foreign policy, East Asian regional security, and resource diplomacy in Africa and Antarctica.