Over the last few years it’s become commonplace for Russia watchers and political scientists to compare Vladimir Putin to Leonid Brezhnev. Both leaders held power over the course of an entire generation and, now for Putin, share the misfortune of having overseen deepening economic and social stagnation. After Putin issued decrees naming his new presidential administration, Carnegie Moscow fellow Alexander Gabuev quipped on Twitter that since 80 percent of the team wasn’t changing, “it’s brezhnevization, but with more advanced medical services for the top leadership.”

The parallels between the two are strong, but Putin faces a different geopolitical and economic environment. Russia is politically isolated from the West and under financial and economic sanctions due to its war in eastern Ukraine and illegal annexation of Crimea. Russia’s lackluster economic growth and development has rendered it increasingly dependent on China for natural resource demand and financing, a situation Brezhnev never faced. But as Brezhnev’s doctors might have joked, different strokes for different folks.

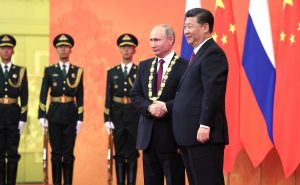

The pomp and circumstance that accompanied Putin’s recent visit to China obscure the real significance of the bilateral deals and statements it yielded. The asymmetries in the relationship are by some turns accelerating and others, stagnating.

Xi and Kasha

While in Beijing, Chinese President Xi Jinping awarded Putin the first-ever “Order of Friendship” for his role in guiding and shaping Sino-Russian relations. The visual was somewhat reminiscent of Brezhnev, known for his love of medals, but was a valuable symbol for domestic and international audiences. While the G7 summit proved a fantastic show of disunity and petty division due to U.S. President Donald Trump, two of the world’s leading authoritarian states managed to display unity. Though significant news emerged from the Beijing visit, details don’t suggest relations are necessarily improving.

Putin’s coterie ambled into town ready to discuss a framework trade agreement that would ideally lead to a bilateral trade deal in about two-and-a-half years. Sources at the Ministry of Economic Development (MinEkonomiki) called the future deal an analogue of the Trans-Pacific Partnership (TPP). That’s a far cry from reality. Certain agreements will likely be reached, but Chinese investors want Russia to better protect their investments, their property rights, and let Chinese firms compete for market share.

The first is unlikely since the Kremlin’s political constituencies of rich businessmen and state firms crucial to the budget enrich themselves at the expense of efficiency, sustainable growth, and partners when possible. The second is even less likely for a similar reason: the power to seize assets is vital to the contract governing Russia’s politics. The third is simply impossible because Russia’s manufacturers employ over 14 percent of Russia’s workforce, often in less populated regions that form a core political constituency for Putin. Introducing competition may threaten the Kremlin’s strategy of maintaining higher employment at the expense of efficiency to prevent protests and dissent from spreading.

The best that can be hoped for is improving market access for sectors in a manner that won’t threaten support. Things like consumer services and e-commerce come to mind.

Invested Interests

In big financial news, China Development Bank (CDB) loaned Vneshekonombank (VEB) more than 600 billion rubles ($9.6 billion). The agreement for the loan was predicated on providing financing for projects linked to Eurasian integration initiatives. VEB mentioned Arctic infrastructure for the Northern Sea Route (NSR) in its press release. Some have perked up at the thought that the money could finance the Moscow-Kazan high-speed rail line that’s been kicked around for several years now.

But there are few concrete projects in the pipeline to develop the NSR, nor is legislation regarding legal responsibility for the NSR even finalized. The route has been given to nuclear giant Rosatom, but many questions remain as to what its powers actually are. Regarding high-speed rail, the proposed Moscow-Kazan route is estimated to cost $20.1 billion thanks to Russia’s inflated construction costs. The money likely has a different purpose despite naming 70 potential projects for joint investment.

Igor Shuvalov, first deputy minister in Prime Minister Dmitry Medvedev’s cabinet until May, now heads VEB. The bank has been tasked with becoming a driver of development meant to help realize Putin’s May decrees concerning various socioeconomic development goals. The reality is that most of the relevant investments into infrastructure do not qualify as pertinent to Eurasian integration. Further, Shuvalov is expected to oversee laying off 40-50 percent of the bank’s employees to improve its efficiency.

Efficiency has become a pressing priority given that VEB has been a clearinghouse for insider deals aimed at maximizing costs to transfer money to friends of the Kremlin. China knows this, which is why VEB is only being given five years to service the loans. Such terms should force VEB to spend on projects, particularly as it’s stipulated by the agreement that they won’t invest more than 30-40 percent of the financing needed for each project to encourage bringing in partners.

But the likeliest scenario is that the bank will funnel the money toward projects whose costs will spiral, thus creating a loop where more money will be loaned via VEB to contractors who should then service that debt to make it appear as though the bank is generating profits. With those profits, they can then argue that efficiency is rising regardless of what gets built or which foreign partners, if any, are involved. Odds are low, particularly with higher oil prices providing more revenues to finance domestic contractors.

By the terms of the loan agreement, it’s clear CDB doesn’t trust Russia to build what it says it will. VEB will have to get creative so it can take the money and run. That’s a template Rosneft – Russia’s largest oil producer – had, until recently, mastered with China.

You’re SOE Vain

Before Putin arrived in Beijing, Rosneft CEO Igor Sechin met with China’s Minister of Commerce Zhong Shan. Although Rosneft’s press release stated that China would “give full support to mutually beneficial investment projects,” the meeting was proof of Rosneft’s declining political stock. The Ministry of Commerce oversees China’s foreign investments. That means the ministry was involved in scuttling CEFC China Energy’s deal to acquire 14.2 percent of Rosneft’s shares last year. No other Chinese firms expressed interest in Rosneft; likely any acquisition of shares in Rosneft was a poor investment. No oil and gas delegations met with Sechin. Rosneft is too politicized, unprofitable, and unwilling to allow large-scale investments into Russian oil and gas fields.

Rosneft’s corporate approach to China may have served the Kremlin’s interests in increasing Russia’s share of China’s oil market, but working with a private sector actor reliant on bad credit without improving its own profitability for shareholders worked at cross purposes to political relations between Moscow and Beijing. China will likely now demand more guarantees of profitability and access to fields, evidenced by reported interest from China National Petroleum Corporation (CNPC) in an LNG project with Novatek – a privately-owned natural gas producer in Russia.

Hairsplitting the Atom

Russian nuclear monopoly Rosatom reached deals with China National Nuclear Power Co. Ltd (CNNPC) to build four reactor units worth an estimated $3.62 billion. The announcement was heralded as Rosatom had successfully beaten out U.S. firm Westinghouse for the contracts. However, the agreement likely came due to pressures facing Rosatom.

In February, the company requested a trillion rubles ($16 billion) to fund the modernization of existing plants and transmission systems. Rosatom aims to match or exceed Gazprom and Rosneft’s investment programs’ annual expenditures by 2023, a pressing priority to position itself to build abroad to advance Russia’s foreign policy aims.

However, the company’s international projects are frequently unprofitable. Oil and gas companies provide real tax revenues, meaning they’re frequently likelier to get what they ask for from Moscow. These deals would likely provide Rosatom a quick cash infusion while providing China another avenue to steal Russian intellectual property and replace Russian expertise and technology domestically over time.

Bilateral Damage

Putin’s visit to Qingdao for the Shanghai Cooperation Organization (SCO) summit offered virtually nothing of substance to assess. Russia’s bilateral agenda with China dwarfs any of the other considerations from the summit. The Qingdao Declaration – the summit’s closing communique – is largely a puff piece filled with hypocritical teeth-gnashing. The tartuffery on display in Qingdao reflected the large gap between Russia’s multilateral rhetoric and the reality of its bilateral relationship with China.

Addressing the summit, Putin noted that “Russia and China are also preparing an agreement on the Eurasian Economic Partnership, which, of course, will be open to all the SCO countries.” Talk of trade multilateralism is farcical for now. Russia lacks proper institutional capacity to carry out trade negotiations with China, let alone the entire bloc simultaneously.

There are no notable China hands within Putin’s presidential administration, there’s no clear organization to the China policy community in Moscow, nor is MinEkonomiki well suited to the task. The ministry has been gutted of much of its institutional heft, likely being handed trade talks so as to hang a sword of Damocles over Minister Maxim Oreshkin’s head. Any trade deal involving the Eurasian Economic Union (EAEU) only adds yet more lobbying considerations and threats to Russian firms’ competitiveness.

A mix of growing dependence on financing, status quo stagnation in energy relations, and stale rhetoric is all Putin could deliver in Beijing and Qingdao. In June of 1978, Brezhnev excoriated Jimmy Carter and the United States for trying to “play the China card” against the Soviet Union. “Its architects may bitterly regret it,” Brezhnev declared. Putin faces no such pressure today but seems happy to play the China card himself. The question remains when he’ll regret it.

Nicholas Trickett holds an M.A. in Eurasian studies through the European University at St. Petersburg with a focus on energy security and Russian foreign policy. He is a columnist and contributor for the Bear Market Brief, a blog and daily news brief on Russia’s politics and economy, and contributes to other outlets like Global Risk Insights, Oilprice, and Newsbase.