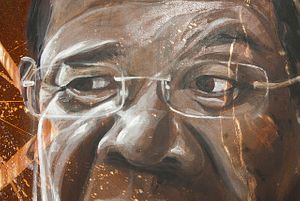

A steady stream of political prisoners has been released since Prime Minister Hun Sen and his long-ruling Cambodian People’s Party (CPP) won all 125 seats contested in the July poll, an emphatic victory made easy by a ban on the main opposition party.

Their release signals a softening in Hun Sen’s approach to dissidents and follows intense lobbying from media organizations, press clubs, advocates like Human Rights Watch and threats of sanctions from the United States and European Union.

Despite the rash of post-election court cases, with charges ranging from treason, defamation and incitement to espionage and producing pornography, Hun Sen insists the courts are simply doing their job, free of government and international interference.

And the courts’ list is a who’s who of politicians from the now banned Cambodian National Rescue Party (CNRP), human rights and pro-democracy advocates, journalists and NGO staffers. But conditions still apply.

Among the first to be released was the enormously popular Tep Vanny, who led the Boeng Kak community in protests against urban land seizures in Phnom Penh.

She received a royal pardon after serving two years for her part in a violent protest but was back in court shortly after and handed a six-month suspended sentence over an alleged death threat made six years ago, which she vigorously denied.

Then 14 members and supporters of the CNRP were also pardoned by King Norodom Sihamoni and released from the notorious Prey Sar prison for their part in riots that followed disputed elections in 2013.

Two journalists, formerly with Radio Free Asia (RFA), were bailed after nine months behind bars. Uon Chhin and Yeang Sothearin still face charges of espionage and producing pornography and face up to 15 years imprisonment if convicted.

Kim Sok was also released after an 18-month jail term for defamation and incitement to cause social disorder. But where others were silent upon release the political commentator was not, accusing the CPP of deploying “tricks” to ensure its victory at the last ballot.

He defiantly added: “I didn’t commit terrorism, I didn’t destroy the government. I only promoted democracy, justice and rule of law.”

Kim Sok has since gone into hiding and is looking for shelter abroad after failing to appear in court on September 14 for questioning. He still owes Hun Sen $200,000 compensation.

It’s a path already taken by veteran journalist, Aun Pheap, who fled fearing arrest following a report he filed for The Cambodia Daily before local elections in 2017. He was granted refugee status by the United Nations and is now living in the United States.

Then, James Ricketson, an Australian film maker and one-time ardent admirer of Sam Rainsy, was pardoned after he was found guilty of espionage and sentenced to six years behind bars.

His crime was flying a drone without a permit above a CNRP rally, allegedly constituting espionage and crimes the prosecution argued had damaged Cambodia’s national security.

Others, however, remain in legal limbo.

For instance, the trial of four human rights activists and an election official known as the “Adhoc 5” is in its third year on charges they bribed a hairdresser to lie about an alleged romantic relationship involving jailed CNRP leader Kem Sokha. A verdict is expected on September 26.

Kem Sokha has been bailed, but remains under house arrest amid his trial for treason. That follows increased pressure from the European Union, which is threatening an end to trade concessions unless all charges against him are dropped.

Former leader Sam Rainsy remains in self-imposed exile amid a string of allegations that includes insulting the monarch, made after he alleged a letter written by the king, urging Cambodians to vote in the July election, was a forgery.

But when it comes to Sam Rainsy, the powers that be may not be in such a forgiving mood. Cambodia’s contentious political climate has cooled in the wake of the July poll, but the heavy hand of Hun Sen’s autocracy still looms large.

Luke Hunt can be followed on twitter @lukeanthonyhunt.