Chinese President Xi Jinping wrapped up a two-day state visit to the Philippines on Tuesday, bringing his three-country, seven-day Asia-Pacific trip to an end. Prior to arriving in Manila on November 20, Xi had been in Papua New Guinea for a state visit and the annual APEC Economic Leaders’ Meeting, then traveled to Brunei.

As Chester Cabalza noted in an earlier article for The Diplomat, Xi’s visit to the Philippines – the first by a Chinese president in 13 years — came after a rocky period in China-Philippines relations. Previous Philippine President Benigno Aquino III adopted a forward-leaning stance on Manila’s territorial claims in the South China Sea, which overlap with Beijing’s own “nine-dash line.” China was especially enraged when Aquino’s administration initiated an international arbitration case against China’s South China Sea claims and conduct.

But by the time that ruling was handed down in July 2016, the Philippines had a new president, Rodrigo Duterte. And Duterte chose to downplay the maritime disputes in favor of courting China for economic benefits – even while distancing his country from its long-time ally, the United States. In the joint statement issued after Xi’s visit, China and the Philippines “reaffirmed that contentious issues are not the sum total of China-Philippines bilateral relations and should not exclude mutually beneficial cooperation in other fields.”

China’s conduct in the South China Sea continues to earn loud condemnation from the United States and others (most recently during the ASEAN summitry in Singapore). Xi’s trips to Brunei and the Philippines were carefully calibrated to combat the bad publicity by helping showcase Beijing as a constructive actor in the disputes. Both Southeast Asian countries are rival claimants in the South China Sea, but (under Duterte, at least) both have adopted a relatively friendly tone toward China despite their maritime discord. According to Chinese Foreign Minister Wang Yi, while hosting Xi, both Brunei and the Philippines “agreed to resolve differences with China through friendly consultations, further maritime cooperation and push talks on a code of conduct in the South China Sea.”

Most notably, China and the Philippines signed a Memorandum of Understanding on Cooperation on Oil and Gas Development. The MoU was much debated prior to Xi’s visit, especially after a Duterte critic leaked a supposed draft. The actual document, however, proved less controversial; it will simply create a government body to study potential models for future projects. Philippine media outlet Rappler reported that “the MOU does not mean the immediate conduct of joint exploration or joint development of marine resources. But it does pave the way for the crafting of a program on how such joint ventures can happen in the future.”

Philippines Foreign Secretary Teodoro Locsin Jr. described the document as “a non-legally-binding framework… [that] shows how you are to proceed so you can prepare for when you start negotiating.” On China’s part, Foreign Ministry spokesperson Geng Shuang said that “China looks forward to advancing the maritime practical cooperation between the two sides in an all-round way and reaping harvests at an early date to benefit the two countries and peoples.”

China has long proposed joint development of natural resources – particularly oil and gas – as a stopgap measure to ease tensions in the South China Sea before resolving the underlying disputes. Conversely, Beijing has threatened other claimants when they attempt to exploit resources in parts of their exclusive economic zones (EEZs) that also lie within China’s capacious “nine-dash line.” For example, last year China reportedly threatened to attack Vietnamese bases in the South China Sea unless Hanoi halted Spanish firm Repsol’s drilling in the South China Sea.

Manila is eager to claim the natural gas believed to lie under Reed Bank – which the arbitral tribunal found China had no rightful claim to. China has blocked such development so far. Some experts see joint development as a solution, while others worry that agreeing to it would legitimize the Chinese claim. Former Foreign Secretary Albert del Rosario urged negotiators on any future joint development deal “to ensure that our Constitution is not violated and our tribunal outcome is not undermined.”

Aside from the South China Sea, promoting the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) was at the top of Xi’s agenda in the Philippines, as it is on every foreign trip by the Chinese leader. The two sides signed a Memorandum of Understanding (MOU) on Cooperation on the Belt and Road Initiative and agreed to several new infrastructure projects, including the Davao City Expressway and Mindanao Railway projects centered on Duterte’s hometown. The joint statement called such infrastructure projects a “highlight of China-Philippines bilateral cooperation.”

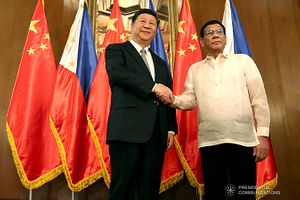

Like Duterte’s visit to China in April 2018, Xi’s trip to the Philippines was a feel-good exercise, with both sides touting their renewed relationship. Xi famously said that the two countries were enjoying the “rainbow after the rain,” a reference to strained relations under Aquino. With Xi’s visit, and the upgrading of their relationship to one of “comprehensive strategic cooperation,” China and the Philippines had “ushered in a new chapter” in their relationship, Xi said.

But questions remain about just how far the relationship can go, especially given their competing claims in the South China Sea. So far, the actual economic benefits of Duterte’s China pivot have been a mixed bag, and anti-Chinese sentiments still run deep in the Philippines. The China-Philippines rapprochement will have an uphill battle to prove it’s more than a beautiful, but temporary, mirage – like an actual rainbow.