Editor’s Note: The following is an edited and compressed version of remarks delivered by the author at a recent workshop in Geneva, Switzerland, hosted by the United Nations, on the international security implications of hypersonic boost-glide weapons.

I’ve been asked to address an important topic that is overdue for serious attention in the area of international disarmament studies and arms control. I’ll be building on the earlier presentation we received from on the state of long-range conventional weapon technology worldwide and focus mainly international security implications of hypersonic weapons, focusing primarily on the subgenre of hypersonic boost-glide weapons — HGVs, for short — which present, in my view, a pressing set of challenges.

HGVs have in recent years been associated with strategic disruption, which has prompted great interest in their potential. In 2013, Russian President Vladimir Putin, in an address to the Federal Assembly, described HGVs as having the potential to “negate all previous agreements on the limitation and reduction of strategic nuclear weapons, thereby disrupting the strategic balance of power.” The fundamental technology behind HGVs is decades old, but years of experience in materials science, weapons development, and growing concerns about missile defenses in some states has led to a recent push for deployable HGV payloads. Russia and China are at the vanguard with dual-capable systems (i.e., Avangard, DF-17, etc), while the United States continues on with its quest to field conventional-only systems for the prompt global strike mission.

The limited bit of good news with regard to HGVs is that many of the challenges they present to strategic stability between the great powers developing them in a serious way — today, China, Russia, and the United States — are effectively new iterations of old problems. Proponents of HGV technology have made the argument, too, that compared to other kinds of prompt-strike conventional weapons, HGVs can offer certain advantages and even offer stabilizing contributions over their counterparts. I will begin with a discussion of these advantages, mostly because the list here is quite short.

Proponents of investments in HGV technology — particularly in the United States Air Force — had made the argument that their unique flight profiles and, in particular, the nonballistic trajectory followed by the reentry vehicle would allow for easy discrimination. In the U.S. context, where these weapons have been strictly conceived of as conventional systems, this attribute was thought to contribute to stability and escalation ceilings. Assumptions in favor of this analytical conclusion are worth appreciating.

First, this assumed that prospective U.S. adversaries — including Russia and China — would have sophisticated enough early warning sensors to discriminate an HGV trajectory from a ballistic trajectory. Second, this assumed, too, that prospective adversaries might forgive — or at least overlook — the maneuverability characteristics that would allow an HGV payload to strike any number of targets once it had been detected. With regard to the assumption regarding sensors, it should be noted that China continues to lack the kind of sophisticated long-range over-the-horizon early warning system that would be required for HGV trajectory discrimination at present. (Investments are being made in this regard, however.)

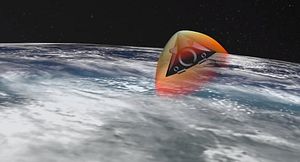

The United States currently operates the most advanced space-based sensor layer, capable of detecting ballistic missile launches with a few seconds of booster ignition given sufficient altitude. What remains unclear is whether these geostationary orbit-based space-based infra-red sensors would be capable of discriminating and detecting the unique heat signatures generated by an HGV in the skip-glide phase of its flight from space. If the answer is no with existing geostationary space-based sensors, then HGVs will continue to pose a destabilizing challenge in their ability to bypass existing early warning systems. By the time terrestrial radars have detected an incoming HGV payload, it may be too late to queue ballistic missile defense systems for engagement or allow national leaders enough time to decide on retaliation, prompting all sides to seriously consider the adoption of dangerous LoW or LUA postures.

I want to interrogate too the often-stated point that one of the greatest challenges from HGV technology in their potential to disrupt the capabilities of existing missile defense systems. This point is commonly associated with HGV technologies. For instance, during his public introduction of the Avangard system in March this year, Russian President Putin described its terminal maneuverability as giving it a capability to become “absolutely invulnerable for any missile defence system.” These claims make for good public relations, but may not entirely be true.

It is conceivable that existing terminal missile defense systems capable of intercepting medium-range-class (MRBM-class) and intermediate-range-class (IRBM-class) ballistic targets could be developed further to manage terminal defense against HGV payloads. The U.S. THAAD, Patriot PAC-3, and MEADS systems could be iteratively improved to handle HGV targets. Similarly, China’s under-development DN-3 and Russia’s S-400 could be calibrated and tested against HGV targets.

The core problem posed by HGVs for existing missile defense architectures rests primarily in the sensor layer. The considerably lower altitude midcourse flight phase for most known HGV systems would considerably reduce the engagement time for ballistic missile systems. This would require tightened battle management system software. While MRBM- and IRBM-class targets can reenter at faster speeds than some HGV payloads and still be successfully intercepted by existing advanced terminal theater-range missile defense systems, it’s still not well-understood just what the outer limits on terminal maneuverability might be for systems like the DF-17, the Avangard, and the U.S. Advanced Hypersonic Vehicle (AHV).

The answer to this question has important implications for how we assess the international security implications of soon-to-be-introduced HGV systems. If they pose an unsurpassable challenge to current-generation terminal missile defense technologies, they stand to qualitatively shift the offense-defense balance in the favor of the attacker. (Ballistic missile reentry vehicles, including maneuverable reentry vehicles, meanwhile allow the attacker to quantitatively overcome even the most effective missile defense systems.)

For Russia and China, there will be an undeniable appeal to design intercontinental-range, nuclear-capable HGVs—especially if their concerns about U.S. midcourse defense aren’t assuaged. Both Moscow and Beijing doubt U.S. assertions that the Alaska- and California-based Ground-Based Midcourse Defense is designed to defend against “limited” ballistic missile threats from states like the DPRK and Iran. Intercontinental-range HGVs would reach their ballistic apogees out of the range of U.S. continental Ground-Based Interceptors and skip-glide at a low enough altitude to guarantee their ability to penetrate through to the U.S. mainland. This problem was identified by U.S. Statergic Command’s chief Gen. John Hyten: “We don’t currently have effective defenses against hypersonic weapons because of the way they fly, i.e., they’re maneuverable and fly at an altitude that our current defense systems are not designed to operate at.”

“Our whole defensive system is based on the assump- tion that you’re going to intercept a ballistic object,” he added, referring to the GMD concept. Even if terminal missile defense against HGVs becomes feasible, it will be infeasible for the United States to deploy terminal defenses to cover a sufficient swathe of its territory.

There is an added technical impulse here. For a given HGV, the greater the terminal maneuverability, the higher the tradeoff in terms of overall payload weight, on average. That should cause both Beijing and Moscow to favor low-yield, compact nuclear weapons over conventional payloads. (In China’s case, however, it would be difficult to justify a low/lower-yield HGV system as long as it continues to formally profess a no-exceptions no-first use posture.)

One final note on HGVs: Given the unproven nature of terminal HGV defense and the likely unsurpassable challenge of midcourse HGV interception, some have called for greater investment into boost-phase technologies to deal with the HGV challenge. Given the strategic depth available to the United States, Russia, and China by the sheer size of their territory, shore-based boost-phase systems or even persistent air-based boost-phase interceptor launchers, such as fighter aircraft or unmanned aerial vehicles, can be easily dealt with by moving launch sites further inland. That leaves open the possibility of space-based missile defense interceptors, which numerous studies have shown to be prohibitively expensive and deploy in numbers sufficient to counter the HGV challenge.

Dual-capable HGVs — that is to say HGVs capable of carrying both nuclear and conventional payloads — represent a particular concern. Chinese and Russian HGVs appear to currently fit into this category. The U.S. intelligence community has assessed that the DF-17’s HGV payload is designed to be dual-capable and the booster itself might be quite similar — or identical — to that used by the DF-16 medium-range ballistic missile. Similarly, Russia’s Avangard is rated by multiple sources as having a capability to deliver both conventional and nuclear payloads. The United States does not appear to be considering dual-capable HGVs at this time; all known U.S. HGV efforts in recent years have been focused strictly on conventional payloads.

In wartime, dual-capable systems raise the risk of inadvertent escalation. In the Pacific, in a U.S.-China conflict, U.S. military planners would have high incentives to disarm China of the conventional systems it might use to strike at U.S. base facilities in the region, which, if disabled, would significantly complicate the United States’ ability to sustain military operations west of the first island chain and toward the Chinese mainland. For Chinese planning purposes, HGV-capable systems like the DF-17 might come to adopt a primary mission in this kind of a scenario — particularly as long as the United States lacks a wide enough low-altitude sensor network in the region to make terminal point defense against HGV payloads viable.

If Beijing comingles nuclear-capable HGVs and conventional HGVs — or comingles People’s Liberation Army Rocket Force nuclear assets with conventional HGVs-bearing units — any U.S. conventional strike would easily be interpreted as an attempt at counterforce. Strictly, China’s no-first use posture would lead us to think that nuclear escalation would still be unwarranted, but a wide enough U.S. attack could threaten China’s retaliatory ability and, particularly given existing Chinese concerns about U.S. damage limitation technologies, including missile defense, use-or-lose incentives rise quickly, no-first use aside. Here, it should be underlined that Beijing’s dual-capable HGVs are not a unique challenge; its extensive range of comingled conventional and nuclear-capable missile and warhead units present a greater challenge.

Early in a crisis or during a war, it would be nearly impossible for the United States to communicate to Chinese leaders — or for Chinese leaders to take seriously — any U.S. assurance that conventional strikes were not designed to disarm China of its strategic deterrent. None of the possible solutions to this problem are particularly appealing. One would be for China to maintain its existing posture, but pursue a large nuclear buildup, ensuring it would have a larger strategic retaliatory capability. Another could be for China to maintain its existing force structure, but shift its posture explicitly to adopt launch under attack (LUA) or even launch on warning (LoW).