To the extent that his words matter and policy has followed suit, President Rodrigo Duterte has tried to engineer a dramatic pivot in the Philippines’ foreign policy. Early in his administration, he antagonized traditional economic and political allies like the United States (then under President Barack Obama) and later the European Union (due to its calls to respect human rights in the midst of the Philippine government’s campaign against illegal drugs). Duterte also promptly initiated a rapprochement with China, and most recently he even began discussions of possible joint exploration of the resources in the West Philippines Sea (Manila’s name for the part of the South China Sea it claims). Duterte claimed all of this is part of an effort to build a more “independent” foreign policy for the country.

There are mixed views on whether and to what extent the country has achieved a truly independent foreign policy, yet one can credit the Duterte administration for its audacity. The Philippines’ relationship with China — even given the territorial disputes — could still be a fruitful one, economically. One question, however, is whether this approach has necessarily yielded more economic benefits for the country.

This brief analysis outlines a surprising trend in terms of the country’s evolving relationship with China — more inflows of tourists and workers, yet still very little by way of investments and trade. These trends raise both opportunities and risks from an economic development and national security perspective.

People Flows

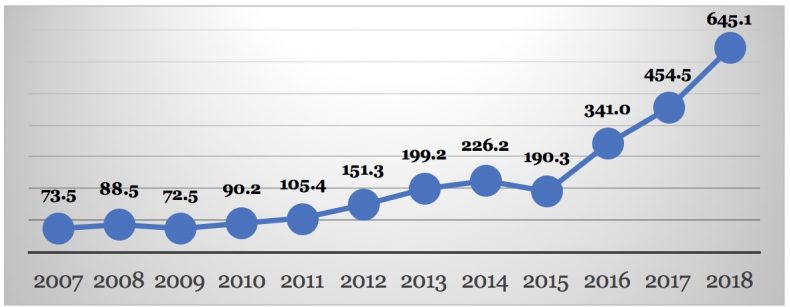

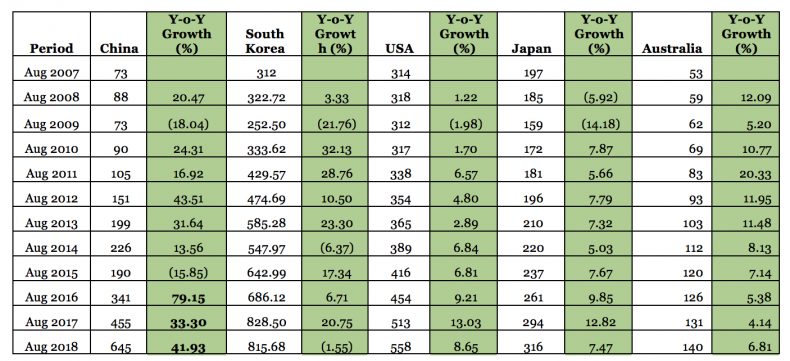

Arguably, the country’s rapprochement with China has drawn more Chinese nationals to the Philippines. As a matter of fact, from August 2015 to August 2016, there was a marked surge – an increase of about 79 percent — in Chinese tourist arrivals. This was followed by 33 percent and 42 percent growth in 2017 and 2018, respectively.

China is now the second largest source of tourists, registering about 645,000 arrivals in the first eight months of 2018 and only behind South Korea.

Figure 1: The number of Chinese tourist arrivals in the Philippines, measured in thousands, from August 2007 – August 2018. Data from the Department of Tourism.

Table 1: Comparison of tourist arrivals in the Philippines by country of origin (in thousands). Data from the Department of Tourism.

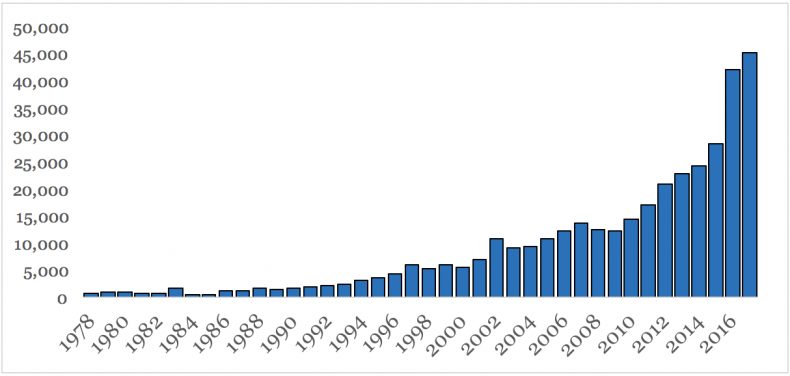

Shadowing this increase in tourism is a reported increase in the number of Chinese workers in the Philippines. In 2016, at least 41,000 foreign workers were given alien employment permits (AEPs) — a remarkable leap of almost 47 percent from the previous year, which saw only about 28,000 working permits.

Of these, Chinese nationals account for a remarkable proportion – some 45 percent — of foreigners issued working permits. Though there seems to be a growing number of officially recognized Chinese workers entering the country as early as 2012, a dramatic spike is very evident since 2016. The number of Chinese workers with work permits grew by about 108 percent between 2015 and 2016 in comparison to a mere 7 percent growth for Japanese and Korean workers combined. The number of Chinese workers then grew by 27 percent in 2017.

Figure 2: The number of foreign nationals issued an Alien Employment Permit (AEP) in the Philippines, 1978-2017. Data from the Philippine Statistics Authority.

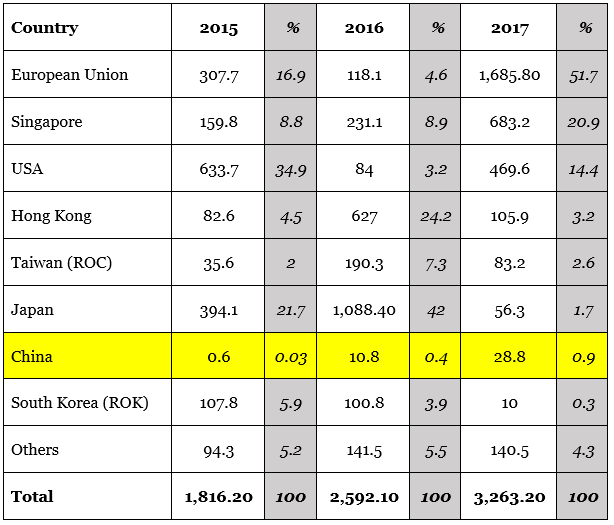

But while the share of Japanese and Korean investments grew by 18.25 percentage points during this period, Chinese investments share expanded by a mere 0.38 percentage points. Clearly, for a smaller share of investments, the Chinese have been sending more workers into the Philippines.

Meanwhile, Philippines-China trade has also experienced a rather mild improvement, rising from $699.48 million to $939.98 million between August 2017 and 2018, a 34 percent increase. Investments from China are also lagging in terms of magnitude, when compared to other source countries. In 2017, China’s share of new capital investments in the country was only a minuscule 0.9 percent of the overall net equity capital.

While it is true that the Philippines saw a surge in equity capital from both China and Hong Kong in 2016, data from the Philippine Central Bank reveals that most of this surge occurred only in the last two months of 2016 — immediately after Duterte’s first state visit to China. The fact that this surge was not sustained, and was still smaller than equity inflows from Japan in the same year, underscores the minor character of the investment gains of the China pivot. Central Bank reports indicate that part of the 2016 China investment surge may have been partly caused by the entry of Chinese offshore gaming firms, though other kinds of investment in the financial sector, real estate, and professional services, among other sectors, were also involved.

Table 2. Net equity capital in the Philippines by source country, 2013 – 2017 (in millions, USD). Data from Bangko Sentral ng Pilipinas (BSP).

Meanwhile, Philippines-China trade has also experienced a rather mild improvement, rising from $699.48 million to $939.98 million between August 2017 and 2018, a 34 percent increase. Investments from China are also lagging in terms of magnitude, when compared to other source countries. In 2017, China’s share of new capital investments in the country was only a miniscule 0.9 percent of the overall net equity capital.

Gambling

Chinese investments have grown dramatically, however, in the areas of real estate and online gaming. In 2016, the Philippine Amusement and Gaming Corp. (PAGCor) issued rules to regulate operations of the Philippine Offshore Gaming Operators, entities who offer online gaming services to foreign players. More than 50 offshore gaming firms were given permits to operate and cater to Chinese clients. The demand for Mandarin-speaking workers, tied together with the more relaxed visa application, helped boost influx of Chinese nationals in the country.

In turn, the resulting immigration led to a high demand in properties near the areas where online gaming firms are located. Ayala Land, one of the county’s biggest real estate developers, revealed that in 2017, 49.4 percent of its international sales were from Chinese buyers. American and Singaporean buyers followed at 15.2 percent and 5.4 percent of sales, respectively.

SM Prime Holdings, on the other hand reported a 10 percent increase (from less than 5 percent in the previous year) in international sales from Chinese nationals. DMCI Holdings, another big player in the real estate development industry, also disclosed that more than 50 percent of their international sales during the first quarter of 2018 were accounted for by the Chinese.

While it’s true that Chinese investors now drive part of the real estate growth in the country today, and that local real estate developers make remarkable profits in the blooming ties between the Philippines and China, this nevertheless leaves the local economy vulnerable in different ways.

One-Sided Economic Growth?

The surge of foreign Chinese workers in the country (mostly toward the gambling areas in Manila Bay) has fueled a scramble for properties for living and working areas — anecdotal evidence suggests that this has increased the real estate prices in some areas particularly affected.

In the last three months of 2017, prices of houses along Manila Bay increased by 27 percent, while condominium unit sales are at an all-time high, with 52,600 units sold in 2017. The increase in housing prices makes living costs for the average family more expensive and may offer them no choice but to move farther away from the areas they prefer to live in.

Meanwhile, reports from a few local government units cited social problems brought about by the influx of Chinese immigrants, which include excessive drinking and gambling.

There has also been speculation that a large number of Chinese immigrants illegally entered and are illegally working in the Philippines. In December 2016 to January 2017, more than 1,000 Chinese illegally working in Clark were caught and sent back to China.

As noted earlier, according to the Department of Labor and Employment (DOLE), only 45,000 foreigners (of these, 29,000 Chinese) have been issued alien employment permits (AEPs) in the Philippines. Yet there are an alleged 400,000 foreigners — most of them Chinese — who are employed by the Philippine Offshore Gaming Operators (POGO). This is almost 10 times the total number of foreigners that received official work permits. If these numbers are true and there are allegations of corruption, then this should be investigated immediately — these raise not simply economic but also national security issues.

The launch of POGO in 2016 by the Duterte administration increased the number of Chinese nationals applying for AEPs, from 5,412 workers in 2013 to 18,920 in 2016. The AEPs are supposed to be issued to foreigners in the event that no local worker is capable of executing the job. This brings up the question of whether these foreign workers actually perform jobs that Filipinos aren’t able to do.

Senator Franklin Drilon raised the issue in a budget hearing by DOLE in September 2018. He charged that Filipinos are being robbed of employment opportunities that Chinese workers have already filled in the online gaming industry.

Similar patterns are apparent in China’s relationship with countries like Cambodia and Laos, as both ASEAN countries have allowed Chinese gambling into their major cities. Thirty Chinese casinos have been already built in Cambodia and an additional 70 are under construction. Upward pressure on the prices of accommodations and real estate properties due to higher demand from Chinese developers has also become common in Laos and Cambodia.

So far the emerging figures from the economic sphere following the Philippines’ rapprochement with China paints a mixed picture. Investments and trade are not dramatically higher — but people flows, in terms of tourists and workers, are up. From an economic perspective, Chinese tourist revenues are definitely a welcome boon to the Philippines’ tourism industry. But more Chinese workers is less appealing, given the country’s challenges to create enough jobs for the vast majority of its young workforce.

(Note that China on the other hand, has not been a traditional destination of overseas Filipino workers due to prior restrictions set by the Chinese government. Based on the records of the Department of Foreign Affairs, only about 13,000 overseas Filipinos were working in Mainland China as of 2017.)

The rising number of Chinese in the country has also raised concerns regarding the Philippines’ national security, particularly since China has continued its very aggressive moves to occupy large parts of the South China Sea. Given pertinent national security issues as regards the country’s relationship with China, these trends clearly need to be monitored using both an economic and national security lens at least.

*The piece has been updated to provide additional clarity on the equity inflows from China and Hong Kong.

Ronald U. Mendoza, PhD is Dean and Associate Professor at the Ateneo School of Government, Ateneo de Manila University in the Philippines. He has worked with UNICEF, UNDP, the Federal Reserve Bank of Boston, the Economist Intelligence Unit (EIU), and several Manila-based non-governmental organizations. He is also currently a Senior Fellow with the East West Institute in New York City.

Miann S. Banaag is a Statistician at the Ateneo Policy Centre, a public think tank housed in the Ateneo School of Government, Ateneo de Manila University in the Philippines. Her current work includes application of empirical and analytical methods in policy research.