From January 7 to 9, a U.S. delegation was in Beijing for talks about trade issues amid an ongoing 90-day truce in the trade war. The delegation, led by Deputy U.S. Trade Representative Jeffrey Gerrish, extended its stay for an additional day; talks had originally been scheduled to conclude on January 8.

Interestingly, while officially this was a vice minister-level dialogue, China’s top man for the trade negotiations, Vice Premier Liu He, made an appearance anyway. A leaked photo of the first day of discussions showed Liu present at the venue, along with Commerce Minister Zhong Shan and Vice Commerce Minister Wang Shouwen (the official head of the Chinese delegation).

According to a brief statement from the Chinese Commerce Ministry, the two sides held an “extensive, in-depth, and detailed exchange” on trade issues, including structural factors. That statement added that the consultations had “established a foundation” for solving the most pressing issues.

At a press conference on January 10, Commerce Ministry spokesperson Gao Feng said the talks had been “solemn, earnest, and candid,” as reflected by the fact that the dialogue was extended by a day. He added that China and the United States would “maintain close communication” on a potential next round of talks.

A statement on the talks from the Office of the U.S. Trade Representative (USTR) did not mention any new breakthroughs, but instead listed longstanding topics of discussion. In that vein, USTR said the talks focused on “ways to achieve fairness, reciprocity, and balance in trade relations between our two countries,” in particular by “achieving needed structural changes in China with respect to forced technology transfer, intellectual property protection, non-tariff barriers, cyber intrusions and cyber theft of trade secrets for commercial purposes, services, and agriculture.” The statement added that talks also “focused on China’s pledge to purchase a substantial amount of agricultural, energy, manufactured goods, and other products and services from the United States.”

Notably, in Thursday’s press conference in Beijing, Gao avoided verifying some of the specifics of the USTR press release, including the promise for China to purchase increased amounts of U.S. goods as well as the specific list of issues covered.

Given the results of the talks, reports of optimism on both sides suggest that Washington may be willing to settle for a deal that mostly involves addressing the trade deficit by increasing U.S. exports to China. There’s little indication of any progress on larger structural changes, including China’s heavy-handed push to promote native-born champions in high-tech industries.

As Hu Xijin, the editor-in-chief of China’s Global Times newspaper, noted on Twitter, trade issues were addressed “most smoothly.” On issues involving “structural changes and cyber security… China accepted parts that are in line with its reform, but rejected requests that harm its national security.” Or, to use President Xi Jinping’s words from a speech in December, “We will resolutely reform what should and can be reformed, and make no change where there should not and can not be any reform.” Unfortunately, China’s definition of what “should not and can not” be reformed has always included precisely the areas of most U.S. concern.

The indication that some progress was made on trade issues but not on structural ones would help explain why it was the United States’ agricultural representative at the talks who characterized the discussion as “a good one for us.” Chinese pledges to increase U.S. imports would naturally center on a boost in agricultural products sent to China. However, U.S. Trade Representative Robert Lighthizer – who was not present for the talks, but who is tasked with overseeing the negotiating effort – has long emphasized a harder stance on the trade issue, one that would necessitate real Chinese action to reform its state-centric economic approach.

Lighthizer’s stance was clearly evident in the USTR press release, which emphasized both structural issues and the need for “complete implementation subject to ongoing verification and effective enforcement” of any eventual agreement. To Lighthizer – and thus the USTR office – China’s promise to buy more U.S. goods is of less interest than the need for “structural changes.” That throws into doubt the possibility of a trade agreement based largely on Chinese promises to raise U.S. imports. Such an agreement, indeed, was previously reached in May 2018, when U.S. Treasury Secretary Steven Mnuchin announced that the trade war had been put “on hold” thanks to China’s pledge to “significantly increase purchases of United States goods and services.” But just days later, President Donald Trump overruled Mnuchin by announcing plans for 25 percent tariffs on $50 billion worth of Chinese imports.

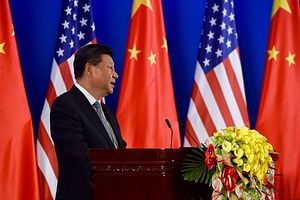

Of course, it’s entirely possible Trump could overrule Lighthizer instead this time, and embrace what is essentially a revamp of Mnuchin’s May 2018 deal as the end of the trade war. Trump has been bullish on a possible agreement since before his breakthrough meeting with Chinese President Xi Jinping in Buenos Aires on December 1, and he tweeted on January 8 that “Talks with China are going very well!”

With the clock ticking down to March 1, when the 90-day trade truce expires, the tug-of-war within the Trump administration over what would constitute success may be even more important than talks with the Chinese.