At their latest “2+2” foreign and defense ministerial consultation in 2018, the Australian and Japanese governments reaffirmed their intention to conclude negotiations on an agreement that will “reciprocally improve administrative, policy, and legal procedures to facilitate joint operations and exercises.” Observers of the Australia-Japan security relationship will note that six months have elapsed since that 2+2 with no finalized agreement, adding that it has been over four years since the two countries first decided to enter negotiations on it. The delays and challenges associated with the negotiation may lead some to believe there are strategic-level seams between Australia and Japan; however, when examined from a broader perspective, the deliberate nature of this process reveals the true importance of this agreement as an epoch-making template for Japan’s 21st century security relationships.

Known as the “Reciprocal Access Agreement,” this instrument of alignment is not only important for the increasingly close security relationship between the two Indo-Pacific powers, it serves as a template both in language and in negotiating process for Japan’s other prospective security partners. Once the intergovernmental negotiation is complete, it will be important to monitor how Japanese lawmakers interpret it during Diet deliberations. The outcome of this entire process will establish an important precedent that will inform Japan’s security relationships for years to come.

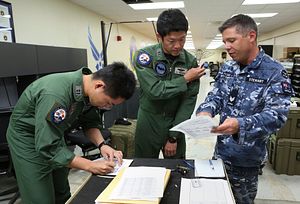

The Reciprocal Access Agreement represents the next step in the bilateral Australia-Japan security relationship that gained new life in 2007 with the “Joint Declaration on Security Cooperation.” Since, the two countries have engaged in routine security dialogues at the 2+2 ministerial level. They signed an updated Acquisitions and Cross-Servicing Agreement in 2017 to provide the legal framework for mutual logistics support. In 2018, the two countries signed a General Sharing of Military Information Agreement to open the door to broader intelligence sharing. All the while, the two countries have been stepping up engagement between the Australian Defence Force (ADF) and Japan Self Defense Force (JSDF), with exercise participation and observation within each other’s territory in Exercise TALISMAN SABER, YAMA SAKURA, and others.

The next step is to formalize the arrangements for the ADF and JSDF operating in partner territory through the Reciprocal Access Agreement (RAA). The RAA will provide the legal framework for operating on foreign soil, covering topics such as taxation, rules for entry and exit of military personnel and equipment into their respective countries, response to mishaps, and criminal jurisdiction, among other issues. It is similar to a Status of Forces Agreement (SOFA), but there is one key difference: SOFAs are for a single host nation and foreign forces stationed in or transiting the host country, whereas the RAA offers reciprocity in the deal where both Japan and Australia would play host nation to the other’s forces — hence the naming convention.

The road to the RAA has been a long one. After formally affirming their intention to negotiate the agreement at their September 2014 bilateral summit, negotiations between the Australian and Japanese governments have taken place intermittently over the past four years. The negotiation has been slow for a number of reasons, many of them political on the Japanese side. The fact remains that the RAA will be the first of its kind for Japan other than its existing Status of Forces Agreements with the United States (1960) and the United Nations Command (1954). The Japanese government is necessarily being careful with the terms of this new agreement for three reasons.

First, it will be different from Japan’s legacy SOFA agreements. There is the obvious circumstance that the United States is a treaty ally while Australia is just an aligned security partner for Japan. This means there are a different set of rights and obligations that will underwrite security arrangements covered in the RAA. There is also the issue of lessons learned from the U.S.-Japan SOFA. The Japanese government wants to avoid damaging its legacy agreements by inadvertently highlighting what it considers to be deficiencies in the SOFA. At the same time, the government does want to pursue certain conditions it wishes it had in place with the United States. The balancing act here requires intragovernmental consensus building, which takes time.

The second reason Japan is being careful is because the RAA must go to the Diet for ratification. As a first-of-its-kind document, the opposition parties will target it in interpellations. Some lawmakers will issue meaningful and important questions about the negotiated agreement, while others will attack anything possible to undermine the ruling coalition. The Japanese government is necessarily taking its time in the negotiations to create as politically airtight a document as possible.

The third reason why the Japanese government is being so deliberate with the process is that this agreement will likely serve as the template for all Reciprocal Access Agreements or Visiting Forces Agreements that follow. Many of the issues that Japan and Australia are negotiating are similar to those that Japan would have to negotiate with the United Kingdom, France, Canada, or others. For Japan, this RAA is not just a negotiation with one security partner, but all the partners that may follow.

From a practical perspective, there is one issue holding up the negotiation, and it centers on Japan’s death penalty. One of the essential items within an RAA or similar instrument is that of criminal jurisdiction. The Japanese government is arguing that any ADF member who commits a crime on Japanese soil while off-duty, especially a heinous crime such as rape or murder, should be subject to Japanese criminal courts. For the Australian government however, this means potentially handing over an Australian citizen to a foreign government where he or she could be handed a death sentence. This would contravene the Australian legal system, which formally abolished the death penalty in 1985. This presents a difficult sticking point on both sides, with the Japanese government reluctant to allow exemptions for ADF soldiers (which would be more lenient than the existing SOFA that exists with the United States), while the Australian government is also reluctant to allow exceptions which could lead to ADF servicemembers facing capital punishment.

Once the governments can settle this issue and agree on an RAA, there remains the additional step of ratification in the Japanese Diet. Based on the numerical strength of the ruling party, passing the RAA will not be an issue. Even if there is a major upset in the House of Councillors election this coming summer and the coalition loses a simple majority (which seems highly unlikely), the Liberal Democratic Party and Komeito ruling coalition can use its two-thirds majority in the lower house to override an upper house decision.

The bigger concern is the interpretation of the RAA that takes place during interpellations. During committee meetings, members of both the ruling and opposition parties are permitted to ask questions on any topic, so the RAA will invariably be subject to scrutiny. The answers that are presented, known as toben in Japanese, are drafted by bureaucrats for the cabinet ministers who have to field the questions. The problems come when cabinet ministers stray from prepared answers, the bureaucrats drafting responses are unfamiliar with the negotiated agreements, or politicians are actively seeking to reinterpret rights and obligations through their responses. In these cases, the toben may intentionally or unintentionally result in a de facto change to a negotiated agreement, though made unilaterally and without specific notification to the Australian government. It will be important to monitor both the negotiated agreement and the toben that follows to provide a clear understanding not only of how far Japan and Australia can operationalize their alignment in each other’s territory, but what prospective security partners can expect from their own future agreements with the Japanese government.

The road to the Reciprocal Access Agreement has been a long one, but Australia is blazing the trail for Japan’s other prospective security partners, too. There are already signals that Japan will pursue a Visiting Forces Agreement with the United Kingdom. France, which has followed Australia and the United Kingdom in signing an ACSA with Japan and stepping up involvement in the region, will probably be next on the list. Japan’s 2018 National Defense Program Guidelines highlights other potential candidates, including Canada and to a lesser extent New Zealand. While there will certainly be unique features in every agreement, the precedent that Australia and Japan are setting will make advancement of those other relationships significantly easier politically while informing expectations for Japan’s security partners. In that respect, the long road to the RAA is not an indication of weaknesses in the Australia-Japan relationship, but of the trust that Japan has placed in it as the model for all others that follow.

Michael MacArthur Bosack is the special advisor for government relations at the Yokosuka Council on Asia-Pacific Studies. Previously, he was the deputy chief of government relations at Headquarters, U.S. Forces-Japan, where he was part of the team that drafted and implemented the 2015 Guidelines for U.S.-Japan Defense Cooperation. While there, he also served as a multilateral coordinator with counterparts from the Japanese interagency, South Korean Ministry of National Defense, and United Nations Command. He is a graduated Mansfield Fellow and a military veteran with two tours in Afghanistan. Follow him on twitter @MikeBosack.