Yang Jiechi is set to visit Japan at the end of this week. Yang, a top Chinese diplomat who previously served as state councilor for foreign affairs (2013-2018) and foreign minister (2007-2013), was elevated to the Politburo of the Chinese Communist Party’s Central Committee at the 19th Party Congress in late 2017. His three-day trip comes amid preparations for a possible visit by Xi Jinping to Japan for the G-20 Summit hosted in Osaka, slated for late June. If Xi goes through with the June trip, it will be the first by a Chinese leader to China’s northeastern neighbor since Hu Jintao visited Japan in 2010.

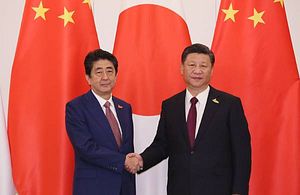

Preparations for Xi’s first visit to Japan as head of state provide added evidence that ties between Beijing and Tokyo are thawing. The two countries have an understandably fraught relationship, with a contentious history and ongoing territorial disputes. However, despite the frostiness that characterized the nature of Beijing-Tokyo exchanges in the first part of Xi’s tenure, a shift appears underway. Diplomatic ties have been on the mend, notably since the 40th anniversary of the China-Japan peace treaty in August 2018 and Japanese Prime Minister Shinzo Abe’s trip to China in October, during which he vowed to usher relations into a new, more conciliatory era.

Last month, Chinese authorities announced the replacement of Beijing’s envoy to Japan. The personnel change may be another indication of China’s bid to improve bilateral relations. The outgoing Chinese ambassador to Japan, Cheng Yonghua, had held his post for nearly a decade. He is reportedly set to be replaced by Vice Minister of Foreign Affairs Kong Xuanyou, who has extensive diplomatic experience with Japan. In a joint interview earlier this week, Kong said, “The foundation of China-Japan friendship lies in people.”

As the two largest economies in Asia, economic ties are the most dynamic facet of the bilateral relationship. China is Japan’s most important trade partner, accounting for 19.5 percent of Japan’s exports and 23.2 percent of its imports in goods in 2018, according to data from Japan’s External Trade Organization. Japan is also party to ongoing negotiations to conclude the China-led Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership (RCEP), a multilateral trade deal that represents 50 percent of the world’s population and 32 percent of global GDP. However, despite the mutual need for positive economic ties, not all is copacetic. China’s slowing growth is a constant concern. Separately, Japan refrained from signing on to the Asian Investment Infrastructure Bank, has called for the Asian Development Bank to end loans to China, and while it recently agreed to collaborate with China on infrastructure and aid projects in Asia, Japan remains an indirect regional competitor for China’s Belt and Road Initiative.

However, the China-Japan relationship is more complex than the bilateral front suggests. The United States continues to play a critical role in shaping dynamics between China and Japan. Washington’s trade war with Beijing has the potential to threaten future economic trends for all three countries, the world’s largest economic powers. Chinese trade losses and ongoing tensions with the United States have led Beijing to warm up to Tokyo. Despite the legacy of strong ties between Washington and Tokyo, Japan has its own frustrations on trade and security, with the Trump administration’s withdrawal from the Trans-Pacific Partnership, hiccups in bilateral trade negotiations, and tough rhetoric over the costs of U.S. basing agreements in Japan. Both Beijing and Tokyo have taken advantage of ripples on the U.S. front to rekindle their bilateral ties.

Still, uncertainty remains regarding the future trajectory of the complex China-Japan relationship. All eyes will be on Xi’s much anticipated Japan trip next month to glean whether the two neighbors can sustain more cooperation or if icy distrust will return as the new normal.