In April 2019 I traveled through northwest Laos to check in on the current state of several cross-border development projects, including the now-completed Namtha dam, the Golden Triangle Special Economic Zone (SEZ), and the construction of a high-speed railway from the Chinese border to Vientiane, part of China’s global Belt and Road Initiative (BRI).

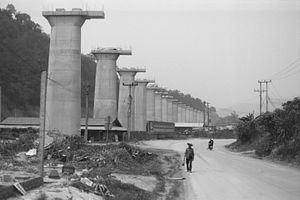

Since my last visit to this area three years before, the exponential acceleration of industrial development had become a de facto scorched earth policy. Entire mountains were raked away, and rectilinear geometries were imposed upon this land of jungled hills. The new railway was gashed through the landscape, covering villages with dust, drilling tunnels through mountains, and erecting obelisk-like structures to raise train tracks above the earth. The SEZ, which had been a garish but slightly ridiculous bubble of development cash on the Mekong, had now conflagrated into a hustling clot of tenement blocks, with a 30-story casino tower of glass and gold at the center, crude metal cages still holding tigers and bears in a “zoo”-cum-3D menu for wildlife cuisine.

April is in the region’s dry season, which has traditionally been used by farmers to burn rice chaff before the arrival of monsoon rains, and by hill peoples to clear new land for swidden fields. But in recent years the dry months have been used to burn vast areas of forest for a variety of economic motives, including the collection of “natural” mushrooms for international sale, and to clear land for plantation agriculture. Now, as hills, jungles, and rivers were bermed and beveled into concrete grids, forests rose into the sky as ash.

No one seems to be able to put the brakes on this system of rapacious extraction, carried out in collusion between the government and multinational corporations. Sombath Somphone, an internationally-recognized community development worker who advocated for village water rights, was disappeared by Lao plainclothes police in Vientiane in 2012. His abduction was caught on video and has been posted online, but this public evidence of government gangsterism has not slowed investment in Laos by the World Bank, the Asian Development Bank, or Western corporations from countries such as France and Norway.

This photo essay begins with the BRI railway construction at the China-Lao border, and follows Route 3 southwest past the Namtha dam to the Golden Triangle SEZ, where the Mekong forms the Lao-Thai border. (I previously documented the Namtha before and during the dam construction in a photo essay for The Diplomat in 2016.) All along the road, the air was funereal, with smoke billowing up from crackling fires at the verge of the disappearing jungle. The gauzy atmosphere gave these landscapes an eerie, ghostly quality, that blurred and dulled my efforts at photography—but, as an anatomy of scorched-earth development in this corner of Laos, maybe the shroud of smoke-haze lends an appropriate veil to the following images.

Scott Ezell is an American poet and multi-genre artist with a background in indigenous cultures and Asian border areas.