When China held the second iteration of its Belt and Road Forum (BRF) last month, Southeast Asian states unsurprisingly factored prominently in both the official guest list and the content of the overall deliberations. But while headlines may suggest a sunny outlook for Southeast Asia’s future role in the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI), in fact they belie a more mixed reality where much of the subregion is still managing the opportunities and challenges within BRI as it evolves.

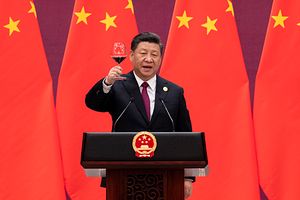

As I have noted before, since the unveiling of China’s BRI in 2013 – with the “Road” component initially rolled out by President Xi Jinping during a visit to Indonesia – Southeast Asia has remained important to the advancement of the initiative. In part, this is due to the fact that China has perceived that it can build on several advantages it has with the subregion that it does not enjoy in other areas to the same degree, be it geographic proximity to its southern provinces or the geopolitical leverage that comes with its growing clout felt in its near abroad in recent years.

That said, thus far at least, as I’ve argued before, the reception to BRI has been mixed in Southeast Asia. On the one hand, Southeast Asian states have recognized the opportunities that come with engaging with Xi’s signature initiative as part of their broader approaches towards China, even though the extent of their involvement thus far involves a mix of old and new projects, with only a few getting off the ground. But on the other hand, these countries have also grown more aware of the challenges that stem from the initiative at home and abroad, whether they relate to individual projects, general functional issues, or the nature of China’s behavior more generally.

The holding of the second iteration of China’s Belt and Road Forum (BRF) once again spotlighted Southeast Asia’s prominent role within the BRI as Beijing seeks to recalibrate how it is approaching and projecting the initiative. This came amid wider regional developments, including continued regional anxiety about the rising U.S.-China tensions and realignments in a number of Southeast Asian states following elections or ahead of key inflection points in their domestic politics.

While some of the headlines may suggest a sunny outlook for China’s BRI in Southeast Asia, the reality was in fact more mixed. On the one hand, Southeast Asia factored prominently when it came to the official guest list and the overall content of the deliberations. Of the 36 heads of state or government that attended the 2019 BRF, nine of them came from Southeast Asia, even though Indonesia, Southeast Asia’s largest economy, was not represented (the country was represented by Vice President Jusuf Kalla).

Southeast Asian states were also included in several agreements publicly disclosed related to BRI, including wider cooperation mechanisms under the BRF framework designed to make the BRI seem more inclusive. This included the Belt and Road Accounting Standards Cooperation Mechanism (with Vietnam and Laos) and a statement of intent for cooperation for pesticide quality specification setting (with Cambodia, Myanmar, the Philippines, Thailand, and Vietnam).

But on the other hand, the progress being touted with respect to Southeast Asia and the BRI should not be mistaken for a full embrace of the initiative. For one, it is unclear how many of the agreements announced at the second BRF – in total “283 concrete results in six categories” per the Chinese foreign ministry – were actually new or implementable. Several of these constitute either the repackaging of older initiatives or limited new convergences, as evidenced by the diversity of mechanisms beyond more binding memorandums of understanding such as declarations of intent.

Furthermore, such forums can obscure the fact that whatever the degree of convergence reached on paper, the extent to which they will translate into reality will play out in broader political environments in these Southeast Asian states with varying degrees of contestation. The timing of the BRF itself was testament to this: It came just after Indonesia and Thailand, Southeast Asia’s two largest economies, held elections, and just ahead of midterm elections for the Philippines. And the importance of this point was reinforced by the fact that we saw instances where engagements by Southeast Asian states at the second BRF were followed by a degree of elite or public opposition, including criticism of the China policy advanced by Philippine President Rodrigo Duterte and Thai Prime Minister Prayut Chan-o-cha.

More broadly, while China has demonstrated that it wants to be seen as taking the concerns of Southeast Asian countries on the BRI seriously, that does not mean that those concerns have gone away. For example, while new initiatives or partnerships in areas like debt issues and environmental sustainability may have roped in some Southeast Asian states such as Cambodia and Myanmar at the second BRF, we have yet to see how rhetoric translates into reality with respect to these serious matters that have generated backlash against the BRI among segments of the population as well as concerned observers, irrespective of official government positions.

There are also broader concerns about China’s behavior that extend beyond the BRI but could also continue to affect it. For instance, Malaysian Prime Minister Mahathir Mohamad made this point about as candidly as he could during his remarks at the second BRF, noting that freedom of navigation was an important concern for all involved in line with the cautious approach Malaysia, a claimant in the South China Sea disputes, continues to take in engaging Beijing. Such issues are not entirely unrelated to the BRI given its broad scope, as evidenced by concerns we have seen regarding potential dual-use facilities in cases like Cambodia.

Finally, it is important to keep in mind that even as Southeast Asian states continue to participate in BRI to varying degrees, they are also engaging with or exploring potential or actual alternatives on their own as well as in collaboration with other countries that could affect their BRI approach in the future. In some cases, this is already ongoing, with one example being the inroads that Japan has been making with respect to promoting quality infrastructure in Southeast Asia as part of its own Indo-Pacific strategy, which Tokyo is expected to further advance at the upcoming G-20 summit next month.

Beyond actual alternatives, potential ones may also lie ahead and ought not to be dismissed, especially given the difficulty of completing infrastructure projects and the long time horizons that some of them have. Indeed, the issue of alternatives is likely to continue to be an issue to watch given the fact that the BRI has had the effect of intensifying the focus on the issue of infrastructure in the wider Indo-Pacific region, leading actors such as the United States to work out what alternatives they can offer and also competing more explicitly with Beijing, including raising concerns about elements of its approach and its system on issues such as 5G and influence operations.

All this is not to understate the inroads that China continues to make in Southeast Asia with respect to the BRI. Indeed, if we see Beijing’s efforts to recalibrate its BRI approach actually concretize in the coming months and years, there could be a greater reception to aspects of it among some Southeast Asian states. But given the concerns that still exist in the region about the initiative and China’s broader behavior, as well as the uncertainties that remain with respect to other variables including domestic politics and the availability of alternatives, the forecast for the initiative appears much more mixed than some of the headlines may suggest.