As expected, China’s hosting of the Second Belt and Road Forum for International Cooperation (BRF) in Beijing, which lasted from April 25 to 27, saw Beijing deliberately seek to recalibrate how it is approaching the much-ballyhooed Belt and Road Initiative (BRI), a signature initiative of President Xi Jinping first unveiled in 2013, amid lingering concerns and challenges. Although this recalibration is not insignificant and bears careful analysis, its extent and impact on the evolution of the initiative and the regional reception to it remains to be seen.

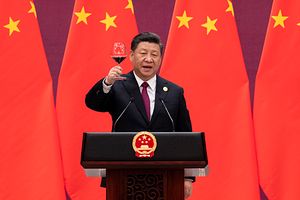

While China’s efforts to recalibrate its BRI approach has in fact been at play over the past few years amid serious regional concerns that remain, the second BRF provided an opportunity for Beijing to officially showcase this effort. In his remarks, Xi predictably touted progress on the initiative but also addressed some of the concerns about the BRI, including exclusivity, sustainability, and standards. The series of outcomes released by the Chinese foreign ministry also reflected this, with the deliberate downplaying of focus on individual projects and Chinese-driven initiatives and inclusion of a list of broader agreements, multilateral frameworks, and people-to-people and cultural initiatives.

While some may find it tempting to dismiss this adjustment entirely, it is in fact not without consequence. China’s recalibration shows that concerns expressed by countries that are part of the BRI, including those who attended the second BRF such as Malaysia, as well as those who did not, such as the United States, is having an effect on Beijing’s calculations. It also shows that China is willing to recalibrate its approach to appear to be addressing at least some of these concerns about Xi’s signature initiative, such as financing and environmental sustainability, and that it needs to make the BRI more inclusive by partnering with other countries and organizations, including development banks.

But just as it is unwise to dismiss China’s ongoing BRI recalibration entirely, it would also be premature to declare that Beijing has settled and rolled out a new version of the initiative that will stick into the future based on what we know now. This is true for several reasons, and three in particular.

First, it is difficult to assess the actual extent of this recalibration. For instance, looking at what the Chinese foreign ministry officially characterized as “283 concrete results in six categories” in a statement released on April 27 following the second BRF, the statement itself admits that some of these results are in fact reaffirmations or repackaging of previous agreements reached, and they were unveiled through a variety of means – including memorandums of understanding, agreement letters, cooperation documents, initiative and mechanism launches, and mere declarations of intent. While that may not necessarily be problematic in and of itself, the fact that this looks much more like a hodgepodge of measures rather than a strategic blueprint does reinforce the need to be cautious about how much of this is new and how much progress has been made to date, especially in the wake of some more sensationalist media accounts.

Second, to the extent that such a recalibration has indeed occurred, it is still unclear how much is stylistic and how much is substantive. For example, while the second BRF saw the showcasing of China’s efforts to address concerns with the unveiling of new initiatives, be it the Chinese finance ministry’s new Debt Sustainability Framework or the China agriculture ministry’s statement of intent for cooperation on promoting specification-setting for pesticide quality with nine South and Southeast Asian countries, it is too early to judge whether this will constitute meaningful efforts that will actually address serious issues of debt and environmental sustainability or mere window dressing. And in spite of the focus on the Chinese government’s efforts, the variables at play in the determination of this in some cases extend beyond the Chinese state, be it the behavior of certain Chinese entities or individual decisions undertaken by regional governments themselves.

Third and finally, it remains to be seen whether this recalibration will actually successfully address the concerns that participating countries, partners, and other outside actors have about the current state and future evolution of the BRI as well as aspects of China’s broader behavior. In his remarks at the BRF, Malaysian Prime Minister Mahathir Mohammad praised the initiative but also diplomatically noted concerning aspects about how the BRI continues to impact freedom and openness in the region. The remarks were an important reminder that while China can help shape the perceptions of these actors and influence individual decisions by recalibrating its BRI approach, it is only part of a range of concerns about China, and how those will be addressed will also depend on how domestic and foreign policy dynamics play out in key individual countries in the coming months and years, whether it be elections, capacity needs, or broader debates about how to engage major powers including China. Seen from this perspective, if the early signs of recalibration are not followed through, that, combined with challenges within key BRI participant countries themselves, could result in a thinning of the broad range of actors that are now willing to engage the BRI in some manner within the current context.

All this is not to dismiss the significance of China’s BRI adjustment, which is notable and offers both opportunities and challenges for those that lie within the initiative and outside of it. But as the headlines continue to roll in about the evolution of BRI following the second BRF, one should be cautious about reading too much into what Beijing is seeking to do and what that means. It is still early days in China’s apparent BRI recalibration, as with other Chinese efforts in this vein, this needs to be given time to materialize to assess its true extent and impact.