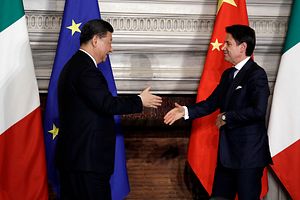

After absorbing negative headlines and growing international criticism for two years, China is working overtime to shore up the reputation of its ambitious Belt and Road Initiative (BRI). In late April it hosted the second Belt and Road Forum summit, drawing dozens of world leaders and thousands of attendees to Beijing to offer their stamp of legitimacy to the initiative. A few weeks earlier, it scored an arguably bigger coup when, during a trip to Rome by Chinese President Xi Jinping, Italy signed a Memorandum of Understanding (MoU) with China governing cooperation under the BRI.

On paper, a non-binding MoU may not appear particularly newsworthy. However, despite five years of heavy promotion, Beijing had until now failed to win a BRI endorsement from any major western European country or member of the Group of Seven (G-7). The vote of confidence from Italy, a NATO member and the eurozone’s third-largest economy, was a feather in the BRI’s cap.

Why did Italy sign the MoU at a time when concerns about the BRI seem to be peaking elsewhere? Look to Italy’s infirmed economy, which is expected to contract by 0.2 percent this year. Public debt now exceeds 130 percent of GDP, and budget deficits are rising. In short, Italy is cash-starved, and President Xi Jinping arrived in Rome with $2.8 billion in investment commitments in tow. As analyst Lucrezia Poggetti observed, Chinese officials informed their Italian counterparts in advance that if Italy did not sign the BRI MoU, the commercial deals on offer would be rescinded.

So, what was in the MoU? Some 29 relatively vague commitments covering infrastructure, trade, and space cooperation, dotted with pledges to increase collaboration in fields such as natural gas and heavy-duty gas turbines. Ten of the commercial agreements signed during Xi’s visit were with private sector companies covering transport, energy, steel, finance, and shipbuilding. The rest were institutional tie-ins, including collaboration in the field of innovation and e-commerce and the elimination of double taxation. Italy’s energy giant Eni won a credit line from the Bank of China. And the state bank of Italy will now sell “panda bonds.”

Perhaps most notably, the China Communications Construction Company (CCCC) was contracted to offer infrastructure support at the Italian ports of Trieste and Genoa. The Trieste agreement concerned railway infrastructure in the port region. In Genoa, the Port Authority contracted CCCC to provide technical support and a new breakwater to protect the coastline.

In sum, the MoU was fairly light on specifics and devoid of some of the geopolitical and transparency concerns that have accompanied the BRI’s troubled record in the developing world — perhaps a reflection of Italy’s stronger negotiating position. The document explicitly states it is not legally binding and is valid for five years unless terminated by either side with three months’ notice.

Despite all this, the BRI endorsement is still controversial at three different levels. First, the MoU was controversial inside Europe, which has been wrestling with how to craft a new model of engagement with a changing China among a divided caucus. France and Germany, in particular, have been resentful of China’s attempt to court and negotiate separately with eastern and central European countries via a “16+1 format.” The strategy is seen by some in western Europe as an attempt to undermine consensus and weaken the EU’s negotiating position.

“In the big EU states, we have agreed that we don’t want to sign any bilateral memorandums but together make necessary arrangements [with China],” German Economy Minister Peter Altmaier explained recently. “For many years we had an uncoordinated approach and China took advantage of our divisions,” French President Emmanuel Macron declared after the MoU with Italy was signed. “The time of European naïveté is ended.”

There are also mounting concerns about the character of China’s growing economic footprint in Europe. According to a recent MERICS report, “China’s BRI-related infrastructure projects are creating fiscal instability in the EU’s regional neighborhood and often fail to align with EU rules and standards for building large-scale infrastructure, from transportation to energy and communications.”

Second, the MoU was controversial within Italy. Notably, Italians hold the most unfavorable views of China among European publics polled by Pew: 60 percent unfavorable versus 29 percent favorable. The debate over the BRI divided the governing right-wing coalition formed between the League’s Matteo Salvini and the Five-Star Movement’s Luigi di Maio. The latter backed the MoU, itself the brainchild of the party’s Michele Geraci, under-secretary of state at the Ministry of Economic Development. Geraci, who spent a decade in Shanghai in the private sector, established his own China Task Force after assuming office and has been shuttling Italian diplomats to Beijing since.

The League party’s Salvini, a deputy prime minister, has been far more circumspect. “Do not tell me that China is a free market. Italy loses 60 billion euros a year to Chinese counterfeits,” he declared the day the MoU was signed. Salvini has since complained that “China is not a democracy and has a certain spirit of imperialism and control” and insisted he would be wary of Chinese investments in the ports of Trieste and Genoa.

Lastly, the MoU was controversial in an international context — so much so that the U.S. National Security Council issued an unusual tweet warning: “Endorsing BRI lends legitimacy to China’s predatory approach to investment and will bring no benefits to the Italian people.” The concern was well-founded: shortly following Italy’s decision, Switzerland signed an MoU to cooperate with China in third countries participating in the BRI and New Zealand signaled a potential softening of its opposition to the initiative.

Arguably more problematic is the prospect that Italy’s decision could ease the pressure on Beijing to reform the initiative. From Sri Lanka to the Maldives, and from Australia to Kenya, critics have been raising legitimate concerns about the BRI’s lack of transparency, accountability, high standards, and fiscal sustainability. There are signs Beijing had begun to internalize this pushback, and perhaps even adapt the BRI in response to these criticisms. If the Chinese government believes it has successfully assuaged these concerns, however, it could weaken the motivation to implement more meaningful reforms.

Italy would have been better served showing solidarity with France, Germany and others and negotiating with China from a position of strength at a time the continent is rewriting the terms of engagement with China. It chose not to. Will it fall victim to some of the strategic pitfalls, white elephant projects, and geopolitical baggage that has accompanied prior BRI deals? Or will it offer a roadmap for how to negotiate with China from a position of strength with deals that prove transparent, financially sound, and serve the interests of the participating country? Europe, the United States, and the world will be watching.

Jeff M. Smith is a research fellow for South Asia in the Asian Studies Center at The Heritage Foundation. Fabio Van Loon was an intern at The Heritage Foundation in the spring of 2019.